2005 will mark the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Industrial Workers World, the I.W.W., popularly known as the “Wobblies.” The most radical, mass-based labor organization to emerge within U.S. history, they embodied the slogan “An Injury to One Is an Injury to All,” as they organized unskilled as well as skilled workers, immigrants as well as the native born, women as well as men, workers of color as well as whites. They practiced internationalism, organizing not only in Canada and Mexico but also across the world. At a grassroots level, the Wobblies employed creative tactics like “striking on the job,” “working to rule,” and “sabotage,” while calling for a general strike to achieve “industrial freedom.” They articulated a vision of a new form of industrial, social, and political order, one in which workers might answer to no authority above their own collective organizations. And they employed culture as a weapon, from poetry and music to cartoons, murals, pageants, and plays.2

There were many difficult and heroic struggles in the Wobblies’ short history — the “free speech” fights from Chicago to the Pacific Northwest, the struggles of timberworkers and migratory harvest hands from the Northwoods to the Plains, the Lawrence, Massachusetts, “Bread and Roses” strike of 1912, the Paterson and Passaic silk workers’ and textile workers’ strikes, the Iron Range strike of 1916, the Bisbee, Arizona, “deportation,” and more, far more. In these struggles, tens of thousands of workers gained a sense of power and agency, political education, and experience with militant industrial unionism which would later underpin the building of the new industrial unions of the 1930s (the “CIO” or Congress of Industrial Organizations). But in these struggles, there were also activists who were jailed, deported, and even murdered, creating a pantheon of heroes.3

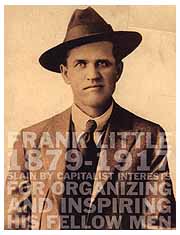

Frank Little was one of these martyred activists. Born in Oklahoma to a white father and a Cherokee mother in 1879, he became an “indefatigable organizer,” an “agitator,” who moved from working-class struggle to working-class struggle in the second decade of the 20th century. In the summer of 1917, the midst of World War I, he brought inspiration and vision to 16,000 miners on strike against the Anaconda Copper Company in Butte, Montana. On August 1, masked men abducted him from the boarding house in which he was staying, tied him to the bumper of a car, dragged him to the outskirts of town, beat and tortured him, and hung him from a railroad trestle. They pinned a note to his body reading: “Others Take Notice. First and Last Warning. 3-7-77.” The numbers, according to filmmaker Travis Wilkerson, were the standard size of a Montana grave and had been used in vigilante actions to signify “frontier justice.” Local authorities ruled that he had been “murdered by persons unknown” and never investigated his murder further. Eight thousand men and women marched in his funeral procession, the largest such event in Butte’s history. In the wake of Little’s death, authorities declared martial law, arrested one hundred I.W.W. organizers for “espionage” and “sedition,” broke the strike, and crushed the union. The Montana sedition law became the model for a federal law, and the Butte wave of repression became the model for the federal “Palmer raids” (named for Attorney General A. Michell Palmer), which destroyed the I.W.W. as a viable organization in 1920.4

Frank Little was one of these martyred activists. Born in Oklahoma to a white father and a Cherokee mother in 1879, he became an “indefatigable organizer,” an “agitator,” who moved from working-class struggle to working-class struggle in the second decade of the 20th century. In the summer of 1917, the midst of World War I, he brought inspiration and vision to 16,000 miners on strike against the Anaconda Copper Company in Butte, Montana. On August 1, masked men abducted him from the boarding house in which he was staying, tied him to the bumper of a car, dragged him to the outskirts of town, beat and tortured him, and hung him from a railroad trestle. They pinned a note to his body reading: “Others Take Notice. First and Last Warning. 3-7-77.” The numbers, according to filmmaker Travis Wilkerson, were the standard size of a Montana grave and had been used in vigilante actions to signify “frontier justice.” Local authorities ruled that he had been “murdered by persons unknown” and never investigated his murder further. Eight thousand men and women marched in his funeral procession, the largest such event in Butte’s history. In the wake of Little’s death, authorities declared martial law, arrested one hundred I.W.W. organizers for “espionage” and “sedition,” broke the strike, and crushed the union. The Montana sedition law became the model for a federal law, and the Butte wave of repression became the model for the federal “Palmer raids” (named for Attorney General A. Michell Palmer), which destroyed the I.W.W. as a viable organization in 1920.4

It is appropriate that the anniversary of the Wobblies’ founding and even these violent, painful events in Butte be observed with cultural projects. The still-existing I.W.W., with the aid of scholar-activists, has created a visual art exhibit to tour the U.S. in 2005.5  Poets, songwriters, muralists, playwrights, and other artists have used their talents to tell these stories and keep them alive for new generations. Poet and playwright Naomi Wallace has written a magnificent poem about Little that deserves to be more widely read.6 She wrote:

Poets, songwriters, muralists, playwrights, and other artists have used their talents to tell these stories and keep them alive for new generations. Poet and playwright Naomi Wallace has written a magnificent poem about Little that deserves to be more widely read.6 She wrote:

DEATH OF A WOBBLY IN MONTANA , 1917

He hears the crowd surge outside the small jail:

a tinker, a tailor, beer-boys paid by

the bank, sour tongued and drunk, the oiled ropes

sweating in their hands. The cops are nowhere.The double door splinters on its hinge

as the prisoner’s mouth dries up on his face.

the citizens break open his cell

with steal pipes, drag him towards the tracks.Twenty, thirty pairs of hands all over,

at his neck, his ankles, between his legs,

kneeing, knuckling, and here and there something

more terrifying than blows: a caress.His flesh resists this outrage but his limbs

flow away from him like water. Dirty

Red, cop-shooter, union bastard, won’t-work-

wobbly. The crowd is taking justice in hand.The whole town shivers behind its doors

and he is at the center of a mob

that smells like a child, of piss, flu and candy.

This is the year of the race riots, KuKlux Klan and conscription. This is the year

of the mustard gas and troop desertions,

the soldiers piled high in Belgian mud

at Passchendaele, their dead hearts breakinginto pieces in their chests like cheap toys.

This is the year strikers take Petrograd.

This is the decade of the dream, obscene

in its hunger and grandeur, when the hordesand filth claim the machinery, when

chaos folds its arms and the world just stops.

The hirelings, as poor as any man,

swell to the river, wealthy with murderand reward. The union man thinks he oughtn’t

to die this way, in terror. He wants to

weep and beg but he can’t, his mouth swirling

with broken teeth and blood. Some of his captorshave no teeth. Their curses slur like a suckling

child. Others are humming, demented

in their desire to make a mark on

the decade, to make a mark on someone’s,anyone’s soul. The leader is a baker.

White flour forms a veil, sifting over

his face as he throws the long rope out

over the trestle, the other end aroundthe young man’s neck. And then abruptly

the raving quits. It’s so quiet they can

hear the river breathe against its rocks.

They lead the prisoner closer to the edge.This is the year America enters

the first world war and the British take

Baghdad. This is the month when the Big Men

in Butte, Montana, pay the Poor Mento destroy their own. This is the hour

when the river crosses itself, white

in the morning light of murder. And yet

the water the prisoner hears belowwill never cover him. He will swing from

the trestle in his black suit like a piece

of tumbled sky. If this day is making

history, this wobbly will never know it.He can no longer see because his eyes

are gone, small blue yolks beneath the boots

of lost men. The hands beating against him

are softer now, like the wings of a birdunder water. Even the words Anarchist,

Pig, traitor, are a caress. But one voice

rises from the swarm (or is it two?)

and whispers close Forgive me, and this voicefrom the strong hand, dead-center on his back.

And as the prisoner’s foot leaves the bank,

he wants to say I love you for he said it

only twice in his life and that doesn’tseem like enough. The voice begs again Forgive

me, Forgive me and the young man says No.

Travis Wilkerson‘s remarkable film, An Injury to One, offers a rich cultural engagement with the Wobblies’ history. It is not just that Wilkerson’s film is, inherently, a cultural project. He has also adopted a particularly cultural approach to his topic. Rather than offering a straightforward historical narrative of the Wobblies, organizer Frank Little’s life and death, and the class struggle in Butte, Montana, in the early 20th century, Wilkerson has chosen a more indirect, intuitive, and creative approach to these subjects. As he argues in the film, since so much of the historical documentation has been lost or destroyed, and since the dominant narratives which remain have been overwhelmingly shaped by the company, telling Frank Little’s story is a creative project, not only a piecing together of fragments of information and a reading between the lines of official accounts and against the grain of newspaper stories, but also a creative weaving of diverse sources that might not seem, at first or even second glance, to have a logical relationship to one another.

An inattentive viewer of this film is apt to feel overwhelmed by its bits of information, unidentified archival photos and contemporary images, grainy art work, and projections of fragmented text. There are occasional references to dates which seem almost random, song lyrics which are not directly connected to the film’s narrative, cartoons and posters which are not credited, and numbers whose significance are not fully explained. One is tempted to ask if this is the first “postmodern” labor history film. But there is considerable method to Wilkerson’s apparent madness, with interesting and effective results.

It is impossible not to get caught up in the sheer beauty of what he has created. The pacing, the sound, the colors, the text, the images, all meld into the antithesis of a disorganized mass of flotsam and jetsam. A rare beauty emerges and offers itself to the viewer. But there is no getting lost, absorbed, here. Wilkerson’s use of text, a sort of exaggeration of Brecht’s use of signage, pushes viewers to think for themselves, to follow not only the language but also the ideas, to think them over. He opens An Injury to One with a line-by-line, even word-by-word, representation of the first lines of the I.W.W.’s “Preamble”: “The working class and the employing class have nothing in common. . . .” The pacing and the placing of the text seem to encourage the viewers to chew over each and every word. At key points in the film, the spoken text, the projected text, the music, and the visuals are jarring in juxtaposition, yet the pace is always slow enough to leave time for thought.

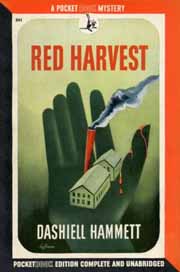

At the same time, he presents his own work to pull disparate pieces together. Wilkerson’s weaving skills are, simply, stunning. Early in the film, he introduces the story of Dashiell Hammett and his hugely popular “noir” detective novel, Red Harvest, which is set in Poisonville, Hammett’s euphemism for Butte. At this point in the film, Wilkerson seems to be merely making a gesture to establish Butte’s location in American popular culture. Later, however, he picks the Hammett thread back up and weaves it together with other information to construct a compelling argument. He notes that Hammett’s close friend Lillian Hellman wrote that Hammett had revealed to her that, while he had been in the employ of the Pinkerton Detective Agency during World War I, the Anaconda Copper Company had offered him $5,000 to kill Frank Little. It was at this point, Hammett averred, that he had realized just how deep corruption had sunk its roots into American life. Late in the film, Wilkerson tells the story of a flock of geese who, caught in a storm in November 1995, landed in Lake Berkeley, a body of water one mile across and 900 feet deep, in Butte. Known locally as “the Berkeley Pit” (“idle like an open wound,” Wilkerson adds), this manmade lake is full of polluted water akin in its chemical composition to battery acid. It is the largest body of contaminated water in the United States. Hundreds of the geese died within a day or two. Butte had become, literally, the embodiment of Hammett’s “Poisonville.”7

At the same time, he presents his own work to pull disparate pieces together. Wilkerson’s weaving skills are, simply, stunning. Early in the film, he introduces the story of Dashiell Hammett and his hugely popular “noir” detective novel, Red Harvest, which is set in Poisonville, Hammett’s euphemism for Butte. At this point in the film, Wilkerson seems to be merely making a gesture to establish Butte’s location in American popular culture. Later, however, he picks the Hammett thread back up and weaves it together with other information to construct a compelling argument. He notes that Hammett’s close friend Lillian Hellman wrote that Hammett had revealed to her that, while he had been in the employ of the Pinkerton Detective Agency during World War I, the Anaconda Copper Company had offered him $5,000 to kill Frank Little. It was at this point, Hammett averred, that he had realized just how deep corruption had sunk its roots into American life. Late in the film, Wilkerson tells the story of a flock of geese who, caught in a storm in November 1995, landed in Lake Berkeley, a body of water one mile across and 900 feet deep, in Butte. Known locally as “the Berkeley Pit” (“idle like an open wound,” Wilkerson adds), this manmade lake is full of polluted water akin in its chemical composition to battery acid. It is the largest body of contaminated water in the United States. Hundreds of the geese died within a day or two. Butte had become, literally, the embodiment of Hammett’s “Poisonville.”7

Wilkerson counterposes and interweaves other odd bits of information to build his analysis. He wants viewers to work through the fog and miasma of official narratives to get at the core of Little’s story. In his narration, he repeats “It is said. . . . It is said” (by the Butte newspapers) that he was an “agitator,” that he practiced “sedition,” that he urged the miners to violence. But Wilkerson’s narration points out that the economic order created by Anaconda and protected by the local and state governments created the conditions in which 10,000 miners died from accidents, injuries, and illnesses. Mortality in Anaconda’s mines was higher than in Europe’s battlefields in World War I, Wilkerson notes, and, a bit later in the film, he adds that Anaconda earned some $25 billion in profits in Butte before abandoning the community and leaving it in its polluted state. When Wilkerson tells his viewers that the local newspaper reported that Little “described the image of a different world,” it is hard not to ponder what that “image” might have been and how it differed from the company-dominated community in which he met his death.

Among the one hundred Wobblies arrested for “sedition” in the wake of the strike, Wilkerson finds, ironically, an individual named “Joseph McCarthy”! When he first mentions this, the viewer might find this tidbit to be grist for a postmodern ironic reading. But later in the film Wilkerson returns to the theme of McCarthyism and the influence of the Wisconsin red-baiter in the 1950s. Dashiell Hammett himself was arrested and jailed in 1951 by McCarthy’s Senate Committee for refusing to name names. The narration suggests that it was in the wake of this experience that Hammett made his confession to Lillian Hellman about having been offered $5,000 in 1917 to kill Little. Cryptically, powerfully, Wilkerson adds: “Sometimes in complex minds it is the plainest experience that speeds the wheels that have begun to move.”

Wilkerson seems unsatisfied to connect only corporate domination to government repression, local repression to national repression, labor history to environmental history, popular culture to the history of class struggle. He must also tell this story in a way that connects the past and the present. He brings his viewers into contemporary Butte, offers odd, touching images of residents at work and play, and tells us that “despite everything the town endures.” Based on his story of the wayward geese, however, he suggests that, despite the destruction of documents, the silencing of witnesses, and the pall of repression, “history cannot be so easily expurgated.” The geese themselves are “directing us to the scene of a crime.”

In the end, Wilkerson closes, the story of Frank Little’s murder demonstrates how “an injury to one” is, fundamentally, essentially, critically, “an injury to all.”

Footnotes

1. Order information: First Run/Icarus Films, 32 Court Street, 21st Floor, Brooklyn, NY 11201. 718-488-8900/800-876-1710. web: frif.com/new2003/inj.html /email: [email protected]

2. On the history of the I.W.W., readers should consult Salvatore Salerno, Red November, Black November (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989); Melvyn Dubofsky, We Shall Be All (Urbana: University of Illioins Press, 2000); Joyce Kornbluh, ed., Rebel Voices (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1964); Steve Golin, The Fragile Bridge (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1988); David Goldberg, A Tale of Three Cities (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1989); Ralph Chaplin, Wobbly: The Rough-and-Tumble Story of an American Radical (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1948).

3. Franklin Rosemont, Joe Hill: The IWW and the Making of a Revolutionary Working-Class Culture (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr, 2003). Please also see the breath-taking review of this book, which covers so many other vital themes and topics, Peter Linebaugh, “Rhymesters and Revolutionaries: Joe Hill and the IWW,” CounterPunch, October 5, 2003 (counterpunch.org/linebaugh10032003.html).

4. William Preston, Aliens and Dissenters (NY: Harper and Row, 1963); Tom Copeland, The Centralia Tragedy of 1919 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1993)

5. For more information on this project, contact [email protected].

6. Naomi Wallace, “Death of a Wobbly in Montana, 1917,” Massachusetts Review 40:1 (Spring 1999). Wallace’s newest play, “Things of Dry Hours,” explores the inner and outer lives of an African American communist in 1932 Birmingham, Alabama. It will receive its world premiere in mid-April 2004 at the Pittsburgh Public Theater. For another compelling poetic elegy to IWW activists, see the opening of Thomas McGrath, Letter to an Imaginary Friend (Chicago: The Swallow Press, 1970). Mark Nowak, the editor of XCP: CROSS CULTURAL POETICS journal (see bfn.org/~xcp/ or email [email protected]) is writing an epic poem called “1916; The Mesabi Miners’ Strike Against U.S. Steel.” Parts of it have appeared in indie magazines CHAIN, TRIPWIRE, and FACTURE.)

7. On Butte’s polluted present, see Jeffrey St. Clair, “Something About Butte,” CounterPunch, January 4, 2003 (counterpunch.org/stclair01042003.html). On Butte’s history, see David Emmons, The Butte Irish: Class and Ethnicity in an American Mining Town, 1875-1925 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1989).

Peter Rachleff is Professor of History at Macalester College. His numerous publications include Black Labor in Richmond, 1865-1890 (University of Illinois Press, 1989) and Hard-Pressed in the Heartland; the Hormel strike and the Future of the Labor Movement (South End Press, 1993).