The premiere of Robert Greenwald‘s new film, Wal-Mart: The High Cost of Low Price, at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, drew a crowd of nearly two hundred people, far exceeding the expectations of the event’s organizers, who were compelled to run simultaneous showings in two separate rooms. Screenings have taken place at thousands of similar venues across the United States. There was no Hollywood Boulevard glitz featuring the film’s stars, no major media advertising campaign, no nationwide Cineplex release, and Director Bob Greenwald has not been featured on Access Hollywood. The Worcester screening was the result of a collaboration between Praxis, a Clark University-based student activist group, Massachusetts Jobs with Justice, and Doug Belanger, a labor organizer for Massachusetts United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) Local 1445 (who also provided free popcorn and soft drinks), and Stacey Schwartz and Chris Sharp of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), who worked diligently to recruit attendees for future Wal-Mart actions. The screening was introduced by Clark University professor and long-time labor activist Robert Ross.

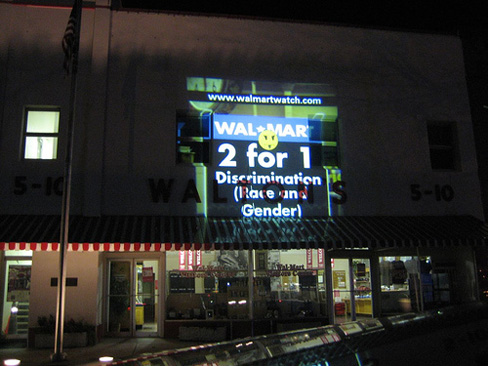

The film is part of a unique effort to mobilize action against the retail giant. Thousands of DVDs are being distributed through a network of grassroots organizations connected to two anti-Wal-Mart groups, Wal-Mart Watch (WalMartWatch.com) and WakeUpWal-Mart (WakeUpWalMart.com), which were set up by an alliance of unions, and environmental, religious, and social justice NGOs as clearinghouses for information on the company. The film had more than seven thousand showings in its first week. It has received substantial coverage by most major commercial and public news outlets, as well as independent and international news outlets. The DVD is available for $12.95, and so are activist kits, which include posters, stickers, fliers, and everything one might require for a public screening.  Many copies of the DVD were distributed for free through Jobs with Justice and other labor groups, as part of a coordinated campaign called the Higher Expectations Week of Action. Nationwide actions were held each day of the week, from film showings to demonstrations outside Wal-Mart stores to anti-Wal-Mart marches and rallies.

Many copies of the DVD were distributed for free through Jobs with Justice and other labor groups, as part of a coordinated campaign called the Higher Expectations Week of Action. Nationwide actions were held each day of the week, from film showings to demonstrations outside Wal-Mart stores to anti-Wal-Mart marches and rallies.

Professor Bob Ross believes that distributing the film in conjunction with a week of action represents a new and exciting form of social movement and organization.  As UFCW organizer Doug Belanger pointed out, the film is a tool for educating people about Wal-Mart’s practices, part of a coordinated nationwide effort to raise public awareness about Wal-Mart just before the biggest holiday shopping season of the year.

As UFCW organizer Doug Belanger pointed out, the film is a tool for educating people about Wal-Mart’s practices, part of a coordinated nationwide effort to raise public awareness about Wal-Mart just before the biggest holiday shopping season of the year.

The film has received a flurry of media attention and commentary from all wings of the political spectrum. Wal-Mart anticipated the film’s publicity with a pre-emptive campaign, which is being coordinated through the company’s “war room,” staffed by expensive former Bush and Kerry presidential campaign publicists, that seeks to counter the most damaging facts presented in the film. The company has also pulled out all stops to ensure the timely release of the film, Why Wal-Mart Works and Why That Makes Some People Crazy, which tells the company’s side of the story. All this attention may make Greenwald’s documentary the most successful, controversial documentary since Michael Moore‘s Fahrenheit 9/11.

But why the storm over Wal-Mart in particular? Wal-Mart CEO Lee Scott states at the beginning of the film, “Today, for whatever reason, whether it is our success or our size, Wal-Mart Stores Incorporated has generated fear and envy in some circles.” Lee Scott’s mystification as to why Wal-Mart is hated is answered by Greenwald and his team, who document, one by one, the social and economic problems stemming from the Wal-Mart business model — the very model that has made Wal-Mart the world’s most admired company among CEOs and on Wall Street, and arguably the most hated company among activists, unions, and small business owners.

What makes Wal-Mart what it is? According to the film, it is the company’s intentional creation of a culture of fear among employees, its low wages, its expensive and low-quality health benefits, and its open hostility to unions. It is the company’s record of discrimination against female employees and those with health problems. It is the company’s indifference to its own impact on the environment. It is the company’s lack of concern for the physical security of its customers. It is the company’s aggressive destruction of local small business competition and its failure to contribute to the welfare of the local communities in which it sets up stores. Belanger argues that it is this set of practices the film seeks to expose and ultimately de-legitimize because the Wal-Mart business model is the standard retail industry model.

But the film itself does not make clear the importance of the Wal-Mart model for the industry as a whole. Rather, the organizers and activists showing the film must connect the dots. As Greenwald acknowledges, “The film will not change people, but it is those who use the film as a tool that are the ones who will effect change.” And here is where the anti-Wal-Mart movement faces its greatest challenge — going beyond established activist groups and building a coalition across traditional political and economic divides.

As a political tool, the film appeals to people’s emotions to try to prompt the audience into taking action (not unlike other propaganda films). Its structure juxtaposes comments from Wal-Mart CEO Lee Scott at the beginning of each segment with the personal and tragic stories of Wal-Mart’s victims and ends with a triumphant flash across the screen of the names of the communities that have been victorious in fighting against the company. Indeed, the emotional charge is powerful, but will it be enough to compel audiences beyond usual activist circles to action, especially those viewing without the benefit of introductory comments by experts and without follow-up Q&A discussions?

Belanger and Ross both echoed this concern, pointing out that while there is virtue in the film’s role as a tool for educating people about the company’s practices, the activists themselves will need to branch out in order to build a broader coalition. While Belanger’s point that the film needs to be seen by relatives, friends, and neighbors who shop at Wal-Mart is shared by many activists, there seems no clear strategy for getting it in front of red-state audiences. And this brings up a striking feature about Greenberg’s film, which is its attempt to appeal to conservatives by capturing the small-town voices of white, conservative, and openly Republican business owners exulting in the nostalgia of Main Street U.S.A. Will the film reach out and affect this audience?

The film’s focus on small-town victims struck Ross as potentially problematic. He feels that the film’s attempt to normalize opposition by prominently featuring white, conservative, small-town business owners ignores the fact that Wal-Mart’s new frontier is dense urban centers, where opposition is more likely to come from unions and community activists, and where substantial numbers of affected people will likely be inner-city blacks and other racial minorities. In fact, a recently leaked internal Wal-Mart document lists the company’s proposed, primarily urban, expansion and building plans for 2006 (see Marcus Kabel, “Wal-Mart Memo Shows Expansion in U.S.,” Associated Press, 14 November 2005).

However, if the film is considered within the context of the larger labor picture, one that includes the Change to Win federation’s recent split from the AFL-CIO, then Wal-Mart: The High Cost of Low Price might be viewed as new labor’s strategy to revitalize the fight in the grassroots tradition. It would also indicate Change to Win’s attempt to extend it base of support into red states and perhaps more importantly to recapture the rhetoric of morality so often conceded to Republicans over the past decade. The success of the film and movement could be the beginning of a change regarding the problem described so well by Thomas Frank in his book What’s the Matter with Kansas?, which accuses the Left of being out of touch with much of America. Belanger is hopeful about the film’s ability to reach beyond the political divide and to serve as a platform from which to begin building a strong coalition of unions, activists, and consumers. Ross seems more hesitant about the film’s uniting potential. He is concerned that the focus on conservative small-town victims comes at the expense of union voices (there is virtually no strong union voice that presents union organizing as the solution to the Wal-Mart problem in the film, save a brief sequence that shows what unionized Wal-Mart workers in Germany enjoy), a decision that may ultimately sacrifice the larger issue of class and strategies for empowering the poor.

The truth may lie somewhere in between Belanger and Ross. A fight against Wal-Mart in the big city could be bolstered by a strong coalition built on a platform that includes labor rights, social justice, and a dose of conservative nostalgia for Main Street U.S.A. There have been stranger bedfellows.

|

“The job of a citizen is to keep his mouth open.” — Günter Grass |

Jayson J. Funke is a graduate student in geography at Clark University, and is a member of the Praxis community.