“Money doesn’t talk, it swears.” — Bob Dylan

The beginning of this year’s holiday season and the Major League Baseball offseason (when most of the trading and dealing of players occurs) has led me to ponder, once again, money and American popular culture. The re-release of Bruce Springsteen‘s 1975 tour de force Born to Run and Patti Smith‘s equally forceful Horses from the same year, along with the 25th anniversary of the murder of John Lennon and the PBS special on Bob Dylan’s early years as an artist, are not only cause for cultural reflection but also a way for the entertainment industry to make even more money from these historical/cultural moments. Our need for culture-cum-entertainment — whether obtained by following the simple intricacies of players batting and throwing a small leather-covered ball around an arbitrarily sized grassy diamond, or by losing oneself in the anarchic throes of a driving rock tune — is virtually universal. Because it is universal, capitalism, in its typical fashion, figured out a way to make a buck from it. Lots of bucks.

Just as the major league owners are big-time money dealers, so are the entertainment heads who own and control the music business. Before the days of free agency in sports, the owners were able to control their players’ destinies. Not just their salaries, but where (and whether) they played. In the early days of rock, record company moguls acted in a similar manner to musicians when they signed bands for as little money as possible, then charged outrageuos studio and tour rates, and kept most of the profits.

When both industries’ profits rocketed into the capitalist stratosphere — mirroring the entire entertainment industry — players of baseball and guitars received larger contracts (after numerous battles with the front office), but only after the moneylenders insured themselves even larger profits.

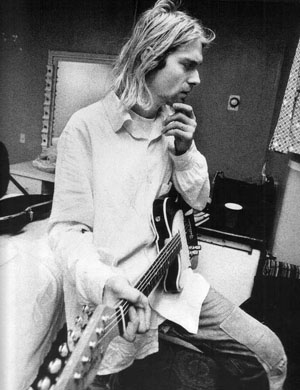

This trend of rewarding the creators of our culture with large sums of money has created not only the Air Jordans of the world — it also spawned those who might have been better off without such riches. The tragic life stories of former New York Mets outfielder Darryl Strawberry and rock artist Kurt Cobain come immediately to mind, as do the deaths of Elvis and Tupac Shakur. For those who don’t pay attention to such things, here are their stories in brief: Strawberry, a gifted player, is currently in prison for consistenlty violating his parole after several convistions for cocaine possession and associated acts. Cobain, blew his brains out in 1994, leaving behind a toddler, wife, and a brilliant career as composer and performer. Elvis died an overweight addict on the toilet. Tupac was gunned down in a pointless murder over non-existent and media-hyped turf differences with other hip-hop artists. In a world where anything which can be packaged and sold is packaged and sold, those with talent must be wary of being commodified.

John Lennon knew this and left the scene for a bit.  Kurt Cobain was also aware of the phenomenon. He was an honest human being. In 1991, an antiwar group aligned with the Olympia Anti-Intervention Coalition asked Nirvana to do a benefit fundraiser against the American slaughter in the Gulf. Kurt said yes immediately. In his interviews and his music, his concern for, and identification with, those of us who aren’t in control of the world is very apparent. It is a shame he and so many other commodified dead artists in the world of corporate culture will never again even have what Cobain termed the “comfort of being sad.” Yet, as this holiday season will prove, their works will continue to produce material comfort for the capitalists that feed off their legacies.

Kurt Cobain was also aware of the phenomenon. He was an honest human being. In 1991, an antiwar group aligned with the Olympia Anti-Intervention Coalition asked Nirvana to do a benefit fundraiser against the American slaughter in the Gulf. Kurt said yes immediately. In his interviews and his music, his concern for, and identification with, those of us who aren’t in control of the world is very apparent. It is a shame he and so many other commodified dead artists in the world of corporate culture will never again even have what Cobain termed the “comfort of being sad.” Yet, as this holiday season will prove, their works will continue to produce material comfort for the capitalists that feed off their legacies.

Ron Jacobs is author of The Way the Wind Blew: A History of the Weather Underground, just republished by Verso. Jacobs’ essay on Big Bill Broonzy is featured in CounterPunch‘s new collection on music, art and sex: Serpents in the Garden. He can be reached at <[email protected]>.