Watching the New York City transit strike from my perch in upstate New York was both exhilarating and frustrating. I felt a swell of pride as the TWU 100 members struck, refusing to “sell out the unborn.” Finally a union took a stand against this nefarious tactic that so many unions had resorted to.

At the same time, as a railroad worker, it was frustrating to see all the abuse heaped on the union and its leadership, and not get a chance to weigh in with all the power that rail labor still has.

Now that the dust has settled, let’s take a look at what the strike revealed. Here’s what I saw.

Labor Solidarity

Most of my co-workers were in instinctive support of the transit workers. They had been through at least one strike experience where they were portrayed as overpaid and greedy. From what I have read and heard from New York City, most workers in the city supported the strike, but it was not long enough to gage how many workers would have turned out in a mass rally.

On the other hand, it appears that behind the scenes, Roger Toussaint, the TWU 100 leader, was getting plenty of pressure from the NYC labor tops to get a grip on the situation before it ran away from leadership control, which would have happened if the strike had lasted a few days longer. The ridiculous fines on the individual workers as well as the union as a whole would have left the workers nothing to lose, giving them no choice but to stay out for total victory, however long it took.

The Press

|

|

The tabloid press revealed its true nature in this strike. Papers like the New York Post and the New York Daily News specialize in day-to-day reporting of blood, guts, and sports that appeal to the lowest common denominator of workers, in order to wheel and turn on them when the chips are down. Then the workers become “rats” who should be “jailed,” as the Post screeched in its notorious front page picture of Roger Toussaint with bars superimposed over his face. We can hope they lost some readers over this.

|

THE TRANSIT STRIKE IN THE NEW YORK TIMES

Sewell Chan and Steven Greenhouse, “From Back-Channel Contacts, Blueprint for a Deal” (23 December 2005); Steven Greenhouse, “New York Transit Deal Shows Union’s Success on Many Fronts” (29 December 2005) |

The New York Times had more balanced, nuanced coverage of the strike, as we would expect from the ruling-class paper of record.

Since I don’t live in New York City, I can’t comment on local TV coverage of the strike, but I am willing to bet it mainly consisted of interviews with passengers inconvenienced by long walks or expensive cab fares.

The Politicians

|

MICHAEL BLOOMBERG

Net Worth: $4.85 Billion “In the spring of 2001, New York magazine quoted Mr. Bloomberg as saying he could not envision spending $30 million on his campaign that year because ‘At some point you start to look obscene.’ He went on to spend $75 million. . . . In February, a couple of months before Mr. Bloomberg began his advertising drive, a New York Times poll found that 43 percent of New Yorkers approved of the job he was doing. Nearly $30 million worth of advertising later, the latest New York Times poll, released yesterday, found 67 percent now approve of the job he is doing” (emphasis added, Jim Rutenberg and Patrick D. Healy, “By Pouring It On, Bloomberg Risks Talk of Overkill,” New York Times, 29 October 2005). “Billionaire Mayor Michael Bloomberg spent more than $77 million to get re-elected, breaking the $74 million record he set in 2001 during his first try at politics . . . . |

It didn’t take long for billionaire Mayor Michael Bloomberg to sink to thinly veiled racial baiting, as he vilified TWU 100’s Roger Toussaint as a leader of “selfish thugs.” Billionaires should really be quite careful about using the word “selfish.” I would like to thank Bloomberg for the education he provided to the working-class public in this case.

Governor George Pataki was MIA for most of the strike, finally stepping in to say that there would be no negotiations without a return to work, even while his man Peter Kalikow, multi-millionaire real estate tycoon chief of the MTA, frantically talked to the union.

If Pataki thought he could use the strike to posture as Calvin Coolidge during the Boston Police strike, he failed. To anyone paying attention, he looked like an idiot.

If Hilary Clinton and other prominent Democratic politicians rushed to the picket lines to show support for the workers, I missed it. MIA sums up their role from what I can see.

The Public

|

ROGER TOUSSAINT IN THE BLACK PRESS

Zita Allen, “TWU Local 100 Pres. Roger Toussaint: Up Close and Personal,” Amsterdam News (8 December 2005); “Roger Toussaint: Everybody’s Person of the Year,” Everybody’s: The Caribbean-American Magazine (December 2005). |

The polls that I know about showed considerable public support for the strike. Predictably, there was a breakdown along racial lines. The TWU 100 local today is majority black and brown in composition. The majority of black public opinion was solidly behind the union. White public opinion was split, roughly half and half. I am willing to bet the supportive half were workers, the other half representing the huge upper-middle professional classes of the New York City metropolitan area who live in the suburbs and who probably regard transit workers as being in the same category as their casual immigrant landscaping and construction help.

The Settlement

My take on the settlement is that the edge went to the union. Not in any overwhelming way, like the Auto Workers victory in 1936, but in an important way, nonetheless.

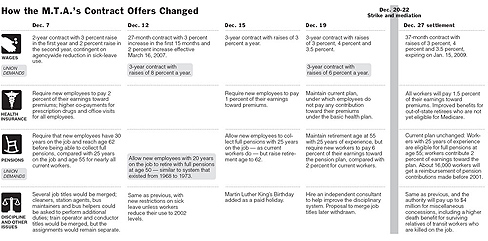

The tentative agreement, which at this time has yet to be voted on, took the critical management provocation and goal off the table. This was of course, the demand that new hires pay more for their pensions than current employees. Accepting this would have opened a permanent cleavage in the union that could only increase over time. As more new employees came on board while older workers retired, the union could be divided over retirement issues in every negotiation, as resentful young workers would be pitted against the retirees that sold them down the river.

Click on the image for a larger view.

This was a strategic question, not a matter of one dollars-and-cents concession amongst many. Understanding this is key to putting this labor battle in perspective. Certainly, explaining this to the broader labor movement is something I feel it is important to do right now.

Jon Flanders is a member and former president of IAM LL 1145 and a member of the Troy Area Labor Council, AFL-CIO.

Jon Flanders is a member and former president of IAM LL 1145 and a member of the Troy Area Labor Council, AFL-CIO.