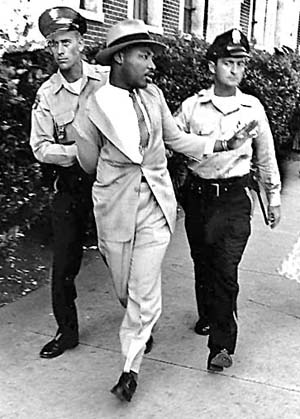

It’s Martin Luther King Jr.‘s birthday and, for the first time since 1977, I am remembering the man and his life in a town below the Mason-Dixon line. At the library I work, Blacks were denied entrance. Denied the right to read a book or study or even get a drink of water. Humans of the darker hue were forbidden the things that King, John Brown, and many others fought and died for, each in their own way. As I listen to a collection of recorded speeches by Dr. King on a local radio station sponsored in part by the NAACP, I still have to fight back tears. It is here in the South — where Africans and their American descendants were enslaved and brutalized, murdered and raped by their owners, the Ku Klux Klan, the police, and racist citizens — it is here where the legacy of Dr. King and the movement against legalized apartheid in the United States means the most.

The radio station is now playing a rendition of the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” sung by a marching band of African-American troops representing the African-American Civil War battalions raised by John Brown’s friend and fervent supporter, George Stearns. The song itself was written by another abolitionist Julia Ward Howe and was based on the song “John Brown’s Body,” which was sung by many a Union soldier as they marched into battle. Even if the original reasons for the Civil War were economic, there were numerous soldiers on the Union side who were fighting to free the slaves. According to many historians, this sentiment became eventually predominant even in the Lincoln White House.

I remember as a young child when my family first moved to Maryland. It was the first time that I saw separate water fountains at the drug store counter. They didn’t last long in the part of the state where my family moved, but the racism and the system it supported remained for quite a while longer. Indeed, it remains to this day, but it is more insidious now. Back then, it was blatant and it was everywhere. It was in the conversations of kids at school and in church. It was in the way African-Americans were referred to in the conversations of many white adults. It was there in the fact that most of the Black people in our town lived in one section of town. It was called “N*ggertown” by most white folks, even though its historical designation was “The Grove.” This section was historically the area where slaves and freed men and women lived.

The Grove was also the place where in 1967 a couple of young men (we called them greasers because they liked fast cars, ducktail haircuts, and Brylcreem in their hair) poured gasoline on a church and tried to burn it down. Once they realized that stone didn’t burn, they took their can of gasoline and lighters across the highway that cut through the heart of the neighborhood and poured it on a house that was occupied by a sleeping family. Fortunately, some of their neighbors smelled the fire and woke up in time to rescue the family and snuff out the fire. It was rumored that the young white men committed the act as part of an initiation process into the local klavern of the KKK. The next morning, there were a lot of angry residents of the Grove, many of them young men and women that I either went to school with or knew from Boys and Girl’s Club. Some of them began throwing rocks at the cars of white folks as they drove through the area on the highway to their homes in more suburban areas of the county. Of course, this brought out the local cops, who began enforcing a curfew.

The curfew didn’t stop the young people from throwing stones. It did get some of the more complacent older African American folks to get involved in some kind of activity that would prevent another attack on their community by individual racists or the police. Together with the NAACP, they asked for permission to have a march through their neighborhood — a march against racism and for healing. The town denied their request, claiming that they did so to prevent trouble. Not long afterwards, the KKK held a march through the same neighborhood their initiates tried to burn down, and they did so with police protection. This attracted the attention of people in Washington, DC. Articles appeared in the Washington Post and an investigation was launched. Some local police were relieved of their jobs — only to get new ones on the County police force. (Prince George’s police are known throughout Maryland for their racism). Things changed a little in that town, just like they have across the US South and across the nation.

Yet, like the Reverend Al Sharpton is saying on the radio right now — “We may have got rid of Jim Crow, but now we are lost in the wilderness. . . . Now we are living with his son Jim Crow, Jr.” I would like to add that junior is a lot meaner and nastier than his daddy ever dreamed of being. Junior even has a good number of black-skinned people helping him out. These folks think that, because they got a college education and played the system’s game as well as the white folk who let them in, they no longer have to remember the history of Blacks in the US. I can’t preach to any one, but I know that when people forget their history, the future will likely be worse.

It ain’t a black thing, either. It’s about all of us. If white people don’t fight racism in our own house, than it will come back to bite us. It ain’t just about skin color — it’s about the rich and the rest of us. It ain’t just about individual racists — it’s about a system that will use racism, war, sexism, and anti-unionism to keep us all down. That system will misuse religion and cheat at politics to stay in power. It will manipulate the media and the educational system and lie for its own sake. That system will decry the bloodshed of its enemies while it makes plans to spread its own murder and mayhem. That system will celebrate Martin Luther King, Jr.’s birthday on the Monday closest to January 15th and then on Tuesday continue its business of war and racism here and everywhere its tentacles of capital can reach.

Ron Jacobs is author of The Way the Wind Blew: A History of the Weather Underground, just republished by Verso. Jacobs’ essay on Big Bill Broonzy is featured in CounterPunch‘s new collection on music, art and sex: Serpents in the Garden. He can be reached at <[email protected]>.