In the past few years, Hayao Miyazaki has finally achieved recognition in the United States as a great filmmaker. Thanks to a deal between his Studio Ghibli and Disney, all of his films will be available in new, uncut English language DVDs; the New York premiere of his latest work, Howl’s Moving Castle, was the climax of a MoMA retrospective, complete with a guest appearance by the Master; and even the New Yorker ran a profile.

Nowhere in this well-deserved attention was there room for the other founder of Studio Ghibli, Isao Takahata. (The best starting point for English-speakers is, with appropriate irony, his page on the Hayao Miyazaki Web.) He fits uneasily into American ideas of animation. Unlike Miyazaki, all of whose films can be seen as fantasy (including the never-land Adriatic of Porco Rosso), Takahata does not appear to be greatly drawn to fantasy subjects. Outside Japan he is best known for The Grave of the Fireflies, which narrates the last days of a pair of children dying of starvation in the closing months of the Pacific War.

In the context of Takahata’s personal work, then, 1994’s Pom Poko (“Heisei Tanuki Gassen Ponpoko” or “Heisei-era Raccoon War Pom Poko”) — released in the US last August — may look like an aberration. It concerns a band of tanuki, raccoon-like animals, biologically very close to dogs, renowned in Japanese folklore as shape shifters, who attempt to stop a development outside of Tokyo that is destroying their forest.

At first, Pom Poko’s “funny-

animal” approach seems more like Animal House than Disney. The tanuki are lazy, overly fond of eating and drinking, and incapable of concentration on the struggle they face. There is a good deal of farce and even a fart joke, and near the end — in a sequence that most American reviewers seem to recall to the exclusion of the rest of the film — they attack a construction crew by squashing them with their hugely inflated testicles.

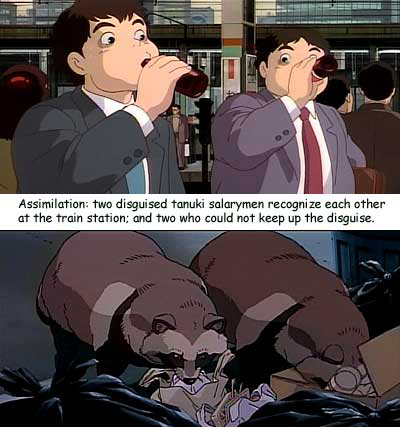

Takahata may be something of a shape shifter himself, stylistically; but just as his tanuki never forget who they are, his films show a consistent vision, fitting the style to the subject rather than imposing a unified style on every topic or exploring the range of expression available within a given stylistic language. Pom Poko’s tanuki are hard to distinguish from each other, especially in their “natural” appearance. (When out of the sight of humans, they are somewhat more anthropomorphic and individualized.) But this suits the film, because it is not about individuals at all; it is about a community. Time spent on individual motivations would blur that focus.

The tanuki are interesting in themselves, but they are also an ideal abstraction with which to address the tragedy of indigenous communities disappearing in the face of an unstoppable global industrial society. Takahata has come close to stating this explicitly, telling an interviewer that people themselves were once tanuki, and elsewhere he has cited the status of the Ainu (the indigenous population of northern Japan) in connection with the film.

Both Miyazaki and Takahata are leftist in sympathies — No-face in Spirited Away is quite obviously an allegorical image of the insatiability of capitalism — and Pom Poko is, in fact, Ghibli’s most political film. The fantasy genre paradoxically allows Takahata to point up the pathos and the human cost of the confrontation more clearly and directly than he could in a film with “real” people.

What begins as farce ends as tragedy. As amusing as some critics found the inflated-testicle scene — it is, by the way, entirely in keeping with Japanese legends — all the tanuki involved in the attack are killed, and later we see their corpses piled up like concentration camp victims. And theirs are not the only deaths.

The turning point of the film comes with the tanuki’s staging of a huge and entrancing demon parade, intended to frighten the residents of the new town into leaving. (This is the film’s visual high point, a virtuoso piece of animation whose whirlwind of images includes some Ghibli in-jokes.) The tanuki had managed to terrorize isolated groups with small-scale reenactments of Japanese ghost stories. But the citified, sophisticated apartment dwellers are not frightened; and worse is to come. As police and the news media investigate, the president of a theme park under construction in the area takes credit. His shows will be so magnificent, he boasts, that he wanted to give the public a taste of the treats to come.

His empty words open the door for the film’s most ambiguous character, a fox who passes as a human being. (The Japanese credit foxes with the same shape-shifting power as tanuki.) He sets out with cruel precision the few options open to the tanuki, which are precisely those faced by indigenous communities caught in the same trap: pass as members of the majority culture, practice your arts in a theme park, abandon those who can’t adjust.

The tanuki struggle against these appalling choices, staging a final illusion: they recreate the image of the rural Japan the town has replaced, hoping to shame the humans into realizing what they have destroyed. The vision, though, breaks their own hearts instead, and reality rushes back.

What is left? Some sail off to die. The rest take the shape of human beings and get jobs, or they live as scavengers in the red light district. The harshness and the banality of their lives is heartbreaking, and in the film’s final sequence a tanuki salaryman, seeing wild tanuki running through a culvert, runs after them, shedding his tie and coat and rejoining old friends in a midnight dance in the middle of a golf course. The tanuki’s joyful song allows the audience to leave with a smile, but it is, alas, the music of a lost paradise.

| Turner Classic Movies will air Pom Poko at 10:15 PM (EST) on Thursday, 26 January 2006 and at 2:45 AM (EST) on Friday, 27 January 2006. |

Michael Steinberg is the author of The Fiction of a Thinkable World: Body, Meaning, and the Culture of Capitalism published this year by Monthly Review Press and essays in professional journals in history, music, and law. He is a member of the literature collective Cat’s out of the Bag. He and his wife Loret, a photographer and professor of documentary photography, live in Rochester, New York, under the supervision of two domestic medium-hair cats.