It’s as if the spotlight that Hurricane Katrina cast on the inequities of disaster relief never happened.

San Francisco’s high and mighty are in full-throated self-celebration of the City’s “rising from the ashes” of the April 18, 1906 earthquake and fire.

Forgotten are people like my great-great grandfather Lee Bo-wen who immigrated to San Francisco Chinatown in 1854 and reared two generations at 820 Dupont Street. His family was forcibly evacuated, never to return.

Even Dupont Street itself vanished forever. Formerly the heart of the community, it was festooned with post-disaster faux Chinese architecture, re-christened Grant Avenue and publicized as the showpiece of the City’s exotic new Chinatown tourist industry.

Indeed, the same scandalous profiteering, racism, incompetence, and mendacity that have characterized the response to Katrina had an antecedent in the San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906.

It is now fully documented that during and after the 1906 disaster, developers, insurance companies, corporations led by the Southern Pacific railroad, City leaders, newspapers, and Army brass brazenly lied and shamelessly promoted anti-Chinese racism to downplay and distort the disaster in order to advance their own selfish agendas.

The 1906 earthquake and fire rendered homeless half of San Francisco’s population of 500,000. It destroyed 28,000 buildings and 498 city blocks.

Authorities claimed that only 300 people had died, the better to undercut claims against the city and the business community. It took decades of painstaking documentation by Gladys Hansen, the city’s archivist, to prove that in fact more than 3,000 had died.

The newspapers and city leaders talked only about the fire because it was considered a more normal event than an earthquake, which they feared would terrify potential investors and affluent homeowners. The San Francisco real estate board met a week after the earthquake and passed a resolution that the phrase “the great earthquake” should no longer be used; it would be known instead as “the great fire.”

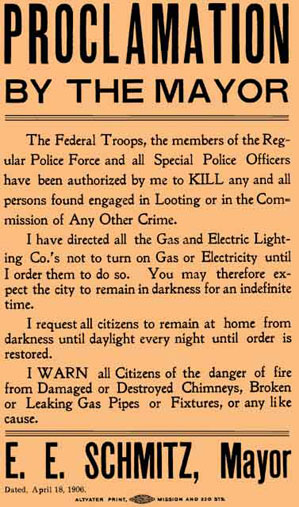

The Army and the police blamed their failure to control the fire on a lack of water. Later it was proved that this was a bald-faced fabrication. Water was plentiful; the problem was that the City and the Army grossly failed to mobilize enough manpower to pump the water and fight the fire.

Meanwhile insurance companies paid up to $15,000 per photo — real or falsified — that could “prove” that a building was damaged by the earthquake rather than the fire, because they were not required to pay for earthquake damage. Businesses and building owners countered with massive arson in order to collect on fire insurance.

And everyone from the Mayor to labor leaders promoted gross racism in order to justify the attempt to grab the prime real estate where thousands of Chinese lived.

The Overland Monthly proclaimed: “Fire has reclaimed to civilization and cleanliness the Chinese ghetto, and no Chinatown will be permitted in the borders of the city . . . . it seems as though a divine wisdom directed the range of the seismic horror and the range of the fire god. Wisely, the worst was cleared away with the best.”

The National Park Service reported that Hugh Kwong Liang, only 15 at the time, recalled, “I turned away from my dear old Chinatown for the last time. City officials directing the refugees’ march approached us and told us to proceed toward the open grounds at the Presidio Army Post.” Despite the presence of the military, newspaper reports tell of extensive looting, including “the National Guard stripping everything of value in Chinatown.”

Click on the image below for a larger view.

Click on an image below to watch a video.

|

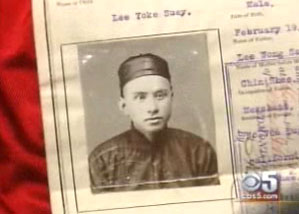

At the same time, the police and National Guard were unleashed against any Chinese suspected of looting. Historian Connie Young Yu recounts that her grandfather Lee Yoke Suey was suspected of looting in his own store and bayoneted. A white crowd stoned to death a young Chinese man who was trying to salvage items from his home.

Chinese refugees quickly flooded relief camps in San Francisco, Alameda, and Oakland. As the Chinese fled burning Chinatown, city officials sought to prevent them from returning. A committee of top leaders was quickly established that focused exclusively on the permanent relocation of the Chinese, finally settling upon distant Hunter’s Point as a likely new location.

The powerful voice of labor, Organized Labor, railed: “Great as the recent catastrophe has been, let us take care lest we encounter a greater one. We can withstand the earthquake. We can survive the fire. As long as California is white man’s country, it will remain one of the grandest and best states in the union, but the moment the Golden State is subjected to an unlimited Asiatic coolie invasion there will be no more California.“

But for the active fight waged by the Chinese community and actively supported by the Chinese consulate, Chinatown might never have been rebuilt.

The Chinese refused to be captured and controlled. The San Francisco Examiner reported: “The committee’s protestations that what it intends is for the benefit of the Chinese is received with suspicion on the part of the Chinese.” Few voluntarily took advantage of relief help when they discovered it meant being held as virtual prisoners in squalid, segregated camps. Despite their estimated population of 60,000, only 186 Chinese refugees remained at the Fort Point camp by May 8.

Meanwhile, Chinatown merchant/property owners who owned one-third of the Chinatown property organized to defend their rights. Dupont Street Improvement Club representatives pointed out that trade in Chinatown the previous year had amounted to $30 million, that the Chinese paid their share of municipal taxes, and that property owners could rent to anyone they wished.

The Chinese government’s consulate also publicly declared its intention to rebuild on its property in San Francisco Chinatown and to protect the rights of overseas Chinese.

Although many Chinese residents were never able to return, the power elite’s plan to destroy Chinatown was foiled by a combination of Chinese resistance and the City’s desire for Chinatown taxes. That latter desire merged with the interests of Chinese merchants so the new Chinatown was shaped to pander to white tourist stereotypes. But at least the community was saved for most of its residents.

My family, like many others, finally settled in Oakland, where they were greeted by the likes of the Oakland Herald: “One of the evils springing from the late disaster to San Francisco, one that menaces Oakland exceedingly, . . . is the great influx of Chinese into this city from San Francisco. Not only have they pushed outward the limits of Oakland’s heretofore constricted and insignificant Chinatown, but they have settled themselves in large colonies throughout the residence parts of the city, bringing with them their vices and their filth.”

To frustrate Oakland’s segregationists, my great-great grandfather anglicized his name from Lee Bo-wen to Lee Bowen and was thereby able to record his purchase of a home in what was then the lily-white Fruitvale district. Legally denied the right to become naturalized citizens, many Chinese took advantage of the destruction of San Francisco’s records to claim U.S. nativity and citizenship.

We failed to learn the lessons of the San Francisco earthquake before Katrina. We must learn the lessons of both now.

It should be crystal clear that disasters are not purely natural events: they can be caused or seriously aggravated by human action like global warming, racism, poor city planning, economic inequality, incompetence, greed, politics, and war.

When a disaster like the SF earthquake or Katrina strikes, your average person empathizes with the appalling loss and pain of the victims and volunteers to help with rescue and reconstruction efforts, contributes money, takes in evacuees, or engages in any number of other humanitarian acts.

But many businesses and politicians act like sharks in bloody waters: they know that disasters open up new opportunities to remake the city in their interests, to make vast sums of money, and to reorganize political power in their favor. They know these events provide a chance to rid themselves of poor communities, especially communities of color, that they consider a blight on their vision for the city and an obstacle to their own enrichment.

Disasters not only reveal hidden inequalities but also grossly aggravate the existing power imbalances between rich and poor, between white and non-white. The power elite has usually planned ahead for disaster, suffers less, and recovers faster from the shock. They have lawyers, bankers, and politicians, ready to fight for their interests.

For most of us, the most vital response to natural disasters — before, during, and after the event — is organizing our communities and workplaces to survive, rebuild, and fight for our interests against the predators in our midst. In areas susceptible to disaster, it is critical to integrate disaster planning into our day-to-day organizing against gentrification and for social justice.

For example, in the Bay Area, we should include planning for the next big earthquake in the ongoing struggle against the gentrification of the Bay View, West Oakland, and other poor communities in the region.

And of course the fight in the Gulf region is still at fever pitch. It is crucial to support the fight to prevent the transformation of New Orleans from a largely black working class city into a gentrified theme park featuring jazz, creole food, and gambling.

Bob Wing is an Oakland Bay Area based activist and writer. Thanks to Nicole Derse, Donna Linden, Richard Marquez, Jane Kim and David Ho for organizing the Ruin, Rubble and Race symposium in San Francisco that inspired and informed this article.