At noon in the hay sheds Lester and me, we kept mostly quiet and old Enos didn’t say much either. Maury and Vern did almost all the talking. Vern was a cowboy, an all-around Marlboro Man, calm and rugged, except that back then he smoked Camels. And Jared, the man we called Preacher when he wasn’t around, he had a little Baptist congregation that couldn’t afford enough salary to keep a roof over his family with enough left over to send two kids to college, which Preacher did plan to do, don’t ask me how. Short-term jobs like bucking bales at Harker’s was the kind of thing Preacher was always fitting into his schedule.

Well, once in a while Maury’d get in cahoots with Vern, the two of them trading off, telling rough stuff, trying to get a rise out of Preacher. Like on this particular Friday noon, Vern told about when he was a kid, his first paying job. One day he was sent back from the baler to fetch a pitchfork.

“We’d lost a fork in the baler. My fault. You know how that is, you’re feeding tall barley or oat straw, and there are times when you stop to wipe sweat or pull down your hat or whatever and the baler grabs the fork and swallows it up, spits it out broke in half and all tied up neat in the bale. Well, I hoofed it to the barn and damned if I didn’t get a view of the foreman trying to hump a half grown Percher on filly.”

“Oh my,” Maury said.

“I slipped out of there quiet as a mouse, went around back, found me a fork, and hi-tailed it out of there.”

“He’d as likely as not killed you,” Maury said.

“Could be,” Vern said.

“Sheep herders have it a lot easier,” Maury said.

Vern looked up at where Preacher was laid back against a bale, his eyes closed. “Jared, how about you giving us heathens some wisdom.”

Preacher opened his eyes, said, “Lust of the goat.”

Vern gave a little grunt of a laugh and shook his head. “Goats, Jared? My oh my, didn’t know you had any experience with goats.”

Preacher stayed calm. “You’re twisting my words, Vern, and you know it.”

Maury said, “Come on, Jared, give us poor sinners a little help.”

Preacher hesitated, then he said, “Mine eyes are upon all their ways; they are not hid from my face, neither is their iniquity hid from mine eyes.”

Maury had his wide mouth open, beautiful white teeth showing, looking well pleased. “Ezekiel,” he said.

“Jeremiah,” Preacher said.

The hay shed went quiet, you could hear the heat crinkling on the metal roof.

“Saieth the Lord,” Maury said.

Preacher nodded and closed his eyes. I wondered where Maury had picked up acquaintance with the Good Book. He’d told us he was nothing but a drifter who’d gone far and wide into many a hard corner. That was one of his sayings. He loved sayings. Well, the Bible is full of sayings, and I knew a few.

Enos gave us all a little snort, took out his turnip watch, flipped up the lid. He put the watch away and got up and went to lean on a post of the shed. I knew what he was looking at, low no-account butte this side of Badger Creek, hot and pale and dry as buffalo bones, and on past to the mountains where elk would be summering, high in the meadows and evergreens and aspens. Whenever they felt like it they’d take a walk along a cool creek, sniff at black currants and geranium and wild parsnip and listen to the creek and take bites of whatever looked good along the way. The rut would be getting to them later, bulls locking antlers with each other and rounding up cows and the cows going along with all of that, and if the Lord had his eyes on them I doubted they’d know it.

Enos came back and closed his lunch pail. Preacher had a watch too, on his wrist. He looked at it. “Sinners,” he said, “it’s time.”

We went back to the fields.

I was broken in by then, knew enough to not wrassle the bales head-on, knew about coaxing them, letting them do a share of the work. On some days, even some of the really tough days, the job would take over, drift us along, dog tired but locked in and not much worried. On that afternoon it was the thought of His eyes looking down on all our ways that kept circling in my mind. By the time we’d stacked our first load in the shed, I’d come to the conclusion that the Lord had to be so all-powerful he couldn’t have eyes because eyes wouldn’t be anywhere near up to the job of taking in everything going on, let alone decide what was iniquitous. Hell, keeping track of me alone would be more than enough to keep him busy. The Lord must have other ways of keeping track, mysterious ways we’d never understand, something like taking on everything all at once, down through the ages and what’s on right now and the future too. I worked on the idea, it really got hold of me, mixed right in there with hay hooks and sweat and the bales taking on extra weight. They always do that, along about three o’clock. But time passed and we topped off the last load and headed for the sheds, Enos driving, Lester and me on top the load catching a little air movement. The other truck was there ahead of us, Preacher on the bed moving bales to the rear, Vern and Maury receiving and stacking. I noticed Maury smiling at Preacher and shaking his head. “There you go again, Jared.”

So, those two had been at it. I wondered if it was about sin and the Lord’s eyes. Preacher stood in hay dust lit up by the sun. He said, “The good book has many a fine aphorism, Maury. They can be a help if you let them. You have to open your heart.”

“There’s danger in opening hearts,” Maury said, and he dug his hooks into a bale and bucked it over to the stack.

“Jesus shows us the way,” Preacher said.

Vern called out. “Enough about the way, feed me some hay.”

Maury was about to snag another bale, but he held back for a couple of ticks, turned a big grin onto Vern. “Good god, Vern, didn’t know you were a poet.”

Vern growled something real low that I couldn’t hear.

We parked the trucks at headquarters and piled into Maury’s pickup, Vern up front with Maury, the rest of us in back catching a soft wind that dabbed at our sweat and itches, and there was the smell of sweet clover from the sides of the road, and once in a while a drift of pine and fir and sage from higher up. At the edge of town Maury stopped to let Vern off. Preacher said, “Isn’t she just lovely?” It wasn’t Preacher’s usual voice, it was almost sermon-like. Jane, Vern’s wife, stood at the mailbox, dressed in bluejeans and a white shirt, smiling at us. Alongside the road, a big Holstein and a half-grown heifer had their heads down in lush grazing, paying no attention to a little towheaded boy who was half hidden in the high growth of timothy and sweet clover. He was making shooing motions and giving the cows what for. “You goddamn cows, you goddamn cows.”

Vern called out, “Hey, where’d you learn talk like that?”

“From me,” Jane said, “and I’ve had it with these goddamn animals.”

“Danny left the gate open again?”

She heaved a big sigh. I guess all of us had our eyes on her. I know for sure mine were, and Preacher, well, his eyes were squinted against the low sun, but they held steady on Jane. I said to myself, “Preacher is a man and his name is Jared.”

Vern went to the cow and turned her but she was taking her time coming back to the gate. She balked there, then decided to go on through and the heifer followed. Danny ran after them, shooing them. Vern had an arm around Jane. She called to us. “Show’s over.” Maury put the truck in gear and we bumped on into town. Maury let us all off at Elmore’s Drugs. Lester slouched off to his end of town. Old Enos eased himself over the tailgate. I heard him tell Maury he’d have his own truck back by Monday and he’d “pick up the kids,” meaning Lester and me. Kids? I felt like telling him a thing or two, but Maury shaded his eyes and winked at me.

Preacher said, “Monday morning, bright and early,” and Maury said, “The Lord willing.”

After supper I walked back to the drugstore, bought a rocky road cone, went outside and ran into Leroy Taylor. He’d been working on Thornton’s thrasher crew, but today they’d started baling alfalfa. Leroy was happy to be finished with thrasher dust. I told him about oversize bales up at Harker’s. It was a fine evening, teetering there on the log that made do as a curb, moths busy banging on Elmore’s windows and nighthawks up in the dark, buzzing and harvesting whatever was up there, and people coming and going. Another hard week behind us. Walking home I looked back on all we’d done on Harker’s big spreads. We’d bucked bales and thrashed oats and dug fence posts, strung barbwire and tightened it guitar-string-tight and repaired barns and corrals, done a hundred different things needed doing, and it occurred to me that work was sort of in charge of all of us. I don’t mean it was watching, checking up on us. No, I don’t mean that at all, that’d be crazy. But it was out there waiting for us. Monday we’d be at it again and I was looking at it and I found it good.

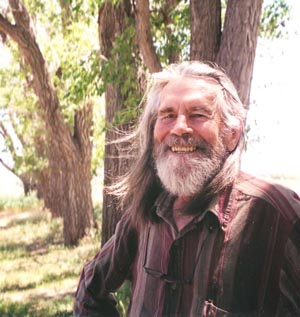

Martin Murie grew up in Jackson, Wyoming; served in the U.S. Army (infantry); studied at Reed College (BA, Literarture and Philosophy) and University of California (PhD, Zoology); taught life sciences at University of Califronia, Berkeley and Santa Barbara, and Antioch College. He retired early, to write. His novels Losing Solitude (1996) and Windswept (2001) were published by Homestead Press and Red Tree Mouse Chronicles (2000) by Packrat Books.

Martin Murie grew up in Jackson, Wyoming; served in the U.S. Army (infantry); studied at Reed College (BA, Literarture and Philosophy) and University of California (PhD, Zoology); taught life sciences at University of Califronia, Berkeley and Santa Barbara, and Antioch College. He retired early, to write. His novels Losing Solitude (1996) and Windswept (2001) were published by Homestead Press and Red Tree Mouse Chronicles (2000) by Packrat Books.