Even before Iran was rocked by the mass uprising of 1978-79, I understood that moralists of all stripes shroud certain tragedies with unique reverence as a means of discouraging dissent. Three decades later, Iran’s opposition movement — and occasionally Human Rights Watch — are grounded in orthodoxies of their own even as they struggles against official moralists. In my dealings with even the enlightened segment of the Iranian movement for political change, I must beware of the political correctness cops. So, before I contradict the usual (“the sky is falling”) reporting on what happened in the women’s well-publicized demonstration last week, a little background.

My parents were modern and secular to a fault (as I still am). Not only my mother and sister drew stares from our neighbors for refusing to cover their hair, we never set foot in a mosque except for an obligatory funeral now and then. Social codes were so strict in our remote community that you would not know Iran’s Islamist Revolution was still a decade away. But we would not conform.

I did join the more traditional teenage boys occasionally during the holy Shi’ite month of Moharram, but only to browse the girls who assembled to watch a passion play. To me, the seventh-century martyrdom of Imam Hussein that local mullahs relied on to preach about good and evil year round was just not exceptional. The human rights catastrophe mourned in my family was the massacre of my father’s clan during Stalin’s purges north of the border. Needless to say, I paid a price for disbelieving the conventional wisdom (I still do).

Then came Iran’s mass uprising in the late 1970s, when the metaphor of Imam Hussein’s defiant last stand fueled the movement that ended monarchy and American dominance in Iran. By that time, a whole generation of university students as well as the Vietnam-era dissidents in Iran blamed the West for Iran’s every ill and had no difficulty signing on to the enshrined victim complex.

A fast-growing lexicon of martyrdom soon found a second application after Iraq, where Sunnis had slain Imam Hussein at Karbala, started a war with Iran with Western complicity that lasted eight years. Murals of that war’s notable martyrs, as well as official admonitions advising women to dress modestly to honor the war dead, still adorn dozens of tall buildings in Tehran.

The few progressive voices that dissented in 1978 and cautioned against blind faith in the Revolution’s religious narrative were sidelined. As is often the case in political campaigns, even the most sincere revolutionaries feared that allowing doubt can benefit the enemy (the Shah’s) camp. It hit me like a ton of rocks to learn that dissidents, too, try to silence dissenters in their own ranks.

In the years that followed, the intellectual tide began to turn against the Imam Hussein narrative, as the educated class felt betrayed by the grassroots flocking to the mullahs. In a remarkable turnaround, it is now high fashion among Iranian opposition factions to blame solely the people of Iran for the country’s “underdevelopment” and the government for its “international isolation.”

Ironically, today’s marginalized political groups have developed a secular equivalent of holy martyrdom to silence doubters in Iran and abroad. As if disagreement with some of the opposition’s agendas is to deny the need for pluralism, anti-government activists are quick to accuse their critics of insensitivity to suffering. Accordingly, most of the opposition sources with whom I am familiar exaggerate the government’s shortfalls and do not tolerate any discussion of its accomplishments.

Some refuse to publicly condemn or even acknowledge far worse human rights abuses committed by Western powers because, they say, this would sound like “regime” rhetoric. (The same folks do not seem concerned that denying the legitimacy of Iran’s government can similarly make them look like US puppets.) In other words, they who complain loudest about the official red lines in public discourse in Iran have red lines of their own.

To me, some of this is reminiscent of the charges of “anti-Semite” and “Holocaust denier” that organized Jewry in America hurls at its critics. CBS television’s Mike Wallace, himself a Jew, learned the hard way to watch his back before reporting that the sky is not falling. He was buried under insults after he reported from Syria, a frontline state at war with Israel, that Syrian Jews were not especially mistreated. In dealing with issues dear to the Jewish community, one is often expected to overlook prevailing exaggerations and double standards out of deference to the lives tragically snuffed out in Nazi gas chambers.

Every film, book, conference, museum, and monument dedicated to the Holocaust now functions also as a deterrent against criticism of Israel. One could reasonably argue, of course, that the Holocaust teaches us to condemn, rather than support, a racist state like Israel. But that is another story. I do not know about you, but I bite my tongue more often than I like to because I do not want to be associated with genocide, or even with discrimination.

On the other hand, the most fundamental principle underlying calls for change in Iran is the right to dissent. The Iranian opposition’s very legitimacy depends on tolerating and even welcoming doubters. It should model the kind of future it promises. Questioning some of its claims is not an insult to those who gave their lives or spent some years of their lives behind bars for the cause. No one owns that legacy. Intimidating dissenters within the opposition camp, however, IS a true betrayal of those who perished or suffered for upholding the right to be irreverent.

I was reminded of all this by conflicting reports about the women’s demonstration in Tehran last week. Contrary to dispatches by news services, I learned from an eyewitness whom I infinitely trust that he saw no beating or gassing of the demonstrators. Having attended the rally as a sympathizer, he believes Iranian women (and men) have every right to press for their demands, without a permit if necessary. But he is also an honest observer. Referring to published photos, he wrote me that some demonstrators were taken away by policewomen, but except in one case they were not physically abused. This is the opposite of what we are told by activist blogs and Western press about the scale and intensity of “the crackdown” on June 12.

The contradiction prompted me to write this commentary, not only because the truth is important for history’s sake and ultimately credibility is a movement’s greatest asset. What especially prompted me to retell the eyewitness account is that sadly my contact in Tehran was unwilling to make his observations public himself for risk of censure. In order to minimize jeopardy to his reputation, I have intentionally not asked for his permission to publicize what he wrote.

Now I quote from his email directly:

All together I would say there were between 150 and 200 protesters and between 40 and 60 male and female police officers. The majority of the women protestors played no active role at all and only by careful attention one could distinguish them from ordinary bystanders. . . .

I witnessed a few women protesters being asked by some female police officers to walk away. In response the protestors [sic] started screaming hysterically at the officers and accused them of beating them, an accusation which looked unsound. “Why are you beating us?”, shouted a woman protestor at a female police officer, who was visibly shaken and became speechless at such an accusation.

Then, for some forty minutes, small groups of women protestors would emerge from different corners of the square voicing their demands for equality of women and against unjust laws and practices. Across the heavy traffic from one corner of the square to another, they would be followed by police officers who would ask them to stop their protest and walk away. Small crowds of bystanders would also converge on these places to see what is going on, as it is typical in the Iranian culture. I did not see any expression of sympathy by these bystanders and onlookers for the cause of the protestors.

In [sic] two different occasions, I saw two groups of protesters, each about four or five, who were arrested and driven away in vans. In one occasion, a woman protestor who was resisting arrest was treated roughly by a female officer, but I saw no beatings, and no use of batons and gas against the protestors. Admittedly, however, I could not be present at all places and at all times to witness all that took place [in the square]. . . .

The next day I was rather shocked to read the biased and distorted BBC report on the event, which was focused on beatings and the use of gas against protestors and was in no way an objective and balanced reporting of what took place, even if away from my eyes some beatings and use of gas had actually taken place.

In an era where every aspect of life in Iran is mischaracterized by powerful outside interests, I believe it is imperative for all sides of every story to find public expression, even when the truth does not help our immediate cause. If, for example, equal rights for women are actually not as popular in Iran as we wish, we would be better off facing the facts and asking what we are doing wrong, instead of inventing excuses or blaming the messenger.

| “President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad . . . criticized the ongoing privatization scheme, which has turned into a means for the ‘looting of national wealth.’

‘I’ve heard that a factory, worth rls 300 billion (USD 32.715 million), is offered at rls 1.050 billion (USD 114,504) . . . . Had the law allowed, we would have given the production unit to laborers free of charge so that it would both remain active and earn profit for the government,’ said Ahmadinejad in a speech to the locals. He said his government does support private investment and business, while believing that the policy should not encourage bankruptcy of workshops, low production, lay-offs and plunder of national wealth. He insisted, ‘The Iranian nation does not accept the sort of privatization at all'” (“Ahmadinejad Protests Plundering National Wealth,” IRNA, 9 June 2006). |

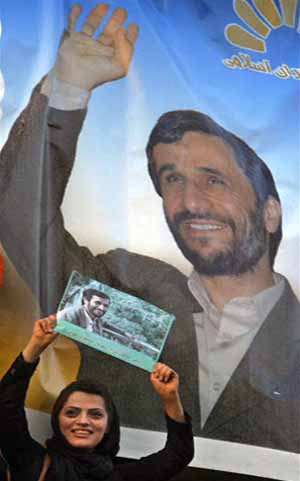

I was stunned during a recent visit to Iran to find that President Ahmadinejad is quite popular among women from all walks of life. Furthermore, a recent telephone survey by a US polling firm found that “Asked about the overall path their country is taking, 71 percent [of the respondents] think Iran is ‘headed in the right direction’ — 18 points higher than in 2005 — while 12 percent disagree with this assessment.”

What is the Iranian public seeing in Ahmadinejad that it doesn’t see in us? Should we be happy or disappointed if the reports of gassing and beating of women on June 12 turn out to be inflated? Can we trust the Western media more than we trust Iranian officials? These are questions worth asking.

Based in Washington DC, Rostam Pourzal writes regularly on the politics of human rights. MRZine has also published Pourzal’s “Market Fundamentalists Lose in Iran (For Now)” (3 August 2005); “Open Letter to Iran’s Nobel Laureate” (27 February 2006); “Open Letter to Iran’s Nobel Laureate: Part 2” (9 March 2006); “The Shah: America’s Nuclear Poster Boy” (25 May 2006); “Iranian Cold Warriors in Sheep’s Clothing” (20 May 2006); and “MEK Tricks US Progressives, Gains Legitimacy” (12 June 2006).