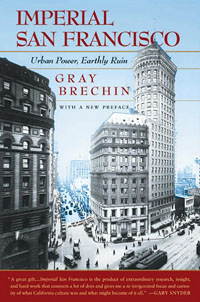

Imperial San Francisco:

Imperial San Francisco:

Urban Power, Earthly Ruin

by Gray Brechin

University of California Press

Every city has its cemetery. But the greatest have mass graves. Beneath St. Petersburg lies a virtual hecatomb — the remains of conscript laborers who died draining the Neva marshes for the palaces of Peter’s courtiers. The Belle Epoque structures of King Leopold’s Brussels are monuments to the massacred villages of the Congo, whose rubber trade made Belgium rich. The Georgian mansions of London, Bristol, and Liverpool — the great ports of the Atlantic slave trade — were built on the brutal exploitation and decimation of an entire race. (Of Liverpool, the progressive historian Charles Beard wrote: “Not without reason did a celebrated actor, when hissed by his audience in that commercial metropolis, fling back the taunt: ‘The stones of your houses are cemented with the blood of African slaves.'”)

San Francisco has its own vicious past, splendidly memorialized. In a city famous for its “Summer of Love,” monuments to war are surprisingly many. Consider Douglas Tilden‘s heroic statue of Bellona, the Roman goddess of war, mounted on a rearing Pegasus where Market crosses Dolores. Tilden’s bronze effigy commemorates the Philippine War, a “protracted war of kindness” that cost the “black wretches” of Luzon several hundred thousand dead. But the war opened the Philippines to San Francisco capital and made the mercantile conquest of the city’s Pacific “hinterland” a stable enterprise. To celebrate this victory, San Francisco illustrators resorted to images of Roman imperial glory: of a Roman centurion straddling the Golden Gate, his sword pointed eastward to Manila Bay; of a Roman goddess accepting tribute from the subject peoples of a “vanquished Pacific.”

San Francisco has its own vicious past, splendidly memorialized. In a city famous for its “Summer of Love,” monuments to war are surprisingly many. Consider Douglas Tilden‘s heroic statue of Bellona, the Roman goddess of war, mounted on a rearing Pegasus where Market crosses Dolores. Tilden’s bronze effigy commemorates the Philippine War, a “protracted war of kindness” that cost the “black wretches” of Luzon several hundred thousand dead. But the war opened the Philippines to San Francisco capital and made the mercantile conquest of the city’s Pacific “hinterland” a stable enterprise. To celebrate this victory, San Francisco illustrators resorted to images of Roman imperial glory: of a Roman centurion straddling the Golden Gate, his sword pointed eastward to Manila Bay; of a Roman goddess accepting tribute from the subject peoples of a “vanquished Pacific.”

It is “Imperial San Francisco” that Gray Brechin makes his subject, in a book subtitled “Urban Power, Earthly Ruin.” Brechin, a geographer at U.C. Berkeley, records the pillage of California and the Pacific rim by San Francisco’s elite: the Big Four of the Southern Pacific; the great Silver Kings of the Comstock Lode; the Hearsts of the Examiner and the De Youngs of the Chronicle. Brechin likens San Francisco and other imperial cities to “maelstroms”: whirlpools that draw the land, labor, and capital of their hinterlands (or “contados” in Brechin’s expression) into their destroying maws.

If this image seems too extreme, one need only recall two examples of destruction: the Hetch-Hetchy, a glacial valley whose beauty was equal to Yosemite’s, flooded to make San Francisco’s water supply secure; and the Owens Valley, a “narrow ribbon of green” in the arid eastern Sierra, drained to slake the thirst of Los Angeles. (The flooding of the Hetch-Hetchy provoked spirited opposition, notably from John Muir; but the draining of the Owens Valley moved its farmers to violent action. They turned to sabotage and blew holes in the aqueduct that carried their water to Los Angeles. When their dynamite tactics failed, they published their surrender in the pages of the Los Angeles Times. “We who are about to die salute you,” they said.)

The tragedies of the Hetch-Hetchy and Owens Valleys are well-documented. But in many historians’ accounts, the true criminals are never named. “San Francisco” and “Los Angeles” are said to be the culprits, as if the populations of great cities could combine to orchestrate a crime. Brechin names names. He has studied the genealogies of the great families, catalogued their marriage announcements and obituaries, and plotted their alliances and misalliances. Sometimes the enmity between two clans has illumined his research — as when the rivalry between the Spreckels’ Call and the De Youngs’ Chronicle exploded in mutual denunciations, exposing the underside of their families’ interests. But more often Brechin’s insights have come through patient scholarship, tracing and re-tracing each family’s ties to clubs and corporations to show the extent of its power and the effects of its depredations. His research has shown him why, among other matters, the De Youngs’ Chronicle so often failed to investigate the Financial District‘s fiascos; and why the Hearsts, who purchased the Chronicle recently, will likely not improve on the De Youngs’ investigative record.

Gray Brechin has written a brilliant study of San Francisco and its monied elite. His book deserves the attention of those who oppose that elite’s dominion and whose vision of San Francisco is not imperial, but just.

Dean Ferguson is an editor of Transformation, a newly launched literary journal. He lives and works in San Francisco.

|

| Print