JASMINE AND STARS: Reading More Than Lolita in Tehran by Fatemeh Keshavarz BUY THIS BOOK |

Fatemeh Keshavarz, author of Jasmine and Stars: Reading More Than Lolita in Tehran, on how literature can be used to create or destroy stereotypes.

Q: How did Jasmine and Stars: Reading More Than Lolita in Tehran come to be?

A: You might say Jasmine and Stars has been in the making for years — at least for a decade. During these years, when many books and media reports about Iran were published, I would search for the Iran that I know, for my friends, for myself. But we wouldn’t be there. Usually in these books and news reports, everything would revolve around religion or politics, and people would be villains or victims. A typical example was Reading Lolita in Tehran: A Memoir in Books by Azar Nafisi, in which a teacher and seven of her female students come together to read world literature and talk about their lives in Iran after the 1979 revolution. I felt like saying to people, “This picture is full of holes! That is not about me! The culture I grew up in has its flesh and blood just like yours. It has good and bad things just like every culture. Shake my hand and you will feel it!” In a sense, Jasmine and Stars is that cultural handshake. It is the opportunity to feel the warmth, the tenderness, and the laughter that I describe from personal experience in present-day Iran. Both Iranians and Americans have been barred from this handshake by the political perspectives that make every American a greedy imperialist and every Iranian a petty fanatic. In Jasmine and Stars I suggest we say enough is enough and talk to each other — we will be surprised at how similar we are.

Q: Does one need to have read Azar Nafisi’s Reading Lolita in Tehran: A Memoir in Books to fully appreciate the message of Jasmine and Stars?

A: If you have read Reading Lolita in Tehran, you might be amazed at the bleakness of the picture that you have seen and crave a balancing perspective. But you don’t have to have read Nafisi’s book to appreciate this one. Jasmine and Stars is an independent book. Its main purpose is to search for a meaningful way to approach an unfamiliar culture, a way in which the humanity and depth of that culture is felt and enjoyed rather than masked from view. At the same time, it critiques the lopsided and exaggerated presentation of the eastern cultures in current western writings, a trend that I call the New Orientalist narrative. Reading Lolita in Tehran is only one example of this kind of writing. However, since I do criticize that book rather sharply, I devote a full chapter to it so I can explain to readers the specifics of my criticism.

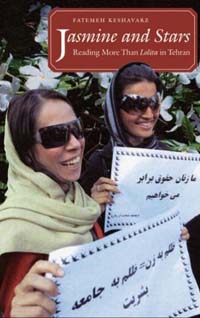

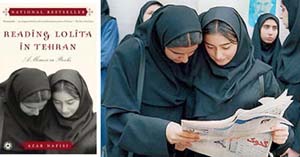

Q: Both Reading Lolita in Tehran and Jasmine and Stars feature a photo of two Iranian women on their jackets — and yet they seem to convey very different messages. Tell me about your book’s jacket photo.

A: The cover of Reading Lolita in Tehran has caused controversy because it presents a cropped image. The full image depicts two young girls, involved in the election of the reformist Iranian President Khatami. The girls are reading a newspaper in anticipation of the election results. In the cover image the newspaper is taken out, leaving two young faces with downcast eyes framed by black scarves. The full and cropped images would send two very different messages about Iranian women to the reader. Critics have compared the book to its cover image because it also omits the aspects of the culture that show that Iranian women have agency and are actively improving their lives. The jacket of Jasmine and Stars shows a full image of two Iranian women in a demonstration outside Tehran University in 2005. The women hold signs that say they object to injustice to women and demand equal rights with men. They smile and look directly at the camera. The goal is not to show a rosy picture of gender equality in present-day Iran — had that been the case, there would be no need for the signs these women carry. The point, however, is that the picture demonstrates women’s agency in the face of all odds and their active presence in the public domain. In other words, the cover shows that Iranian women are not passive victims.

A: The cover of Reading Lolita in Tehran has caused controversy because it presents a cropped image. The full image depicts two young girls, involved in the election of the reformist Iranian President Khatami. The girls are reading a newspaper in anticipation of the election results. In the cover image the newspaper is taken out, leaving two young faces with downcast eyes framed by black scarves. The full and cropped images would send two very different messages about Iranian women to the reader. Critics have compared the book to its cover image because it also omits the aspects of the culture that show that Iranian women have agency and are actively improving their lives. The jacket of Jasmine and Stars shows a full image of two Iranian women in a demonstration outside Tehran University in 2005. The women hold signs that say they object to injustice to women and demand equal rights with men. They smile and look directly at the camera. The goal is not to show a rosy picture of gender equality in present-day Iran — had that been the case, there would be no need for the signs these women carry. The point, however, is that the picture demonstrates women’s agency in the face of all odds and their active presence in the public domain. In other words, the cover shows that Iranian women are not passive victims.

Q: What, in your opinion, was the greatest omission in Reading Lolita in Tehran?

A: The greatest omission in the content of Nafisi’s book is that it overlooks the agency and presence of Iranian women in the social and intellectual domain. That is ironic particularly because the book’s main claim is to tell the untold story of women in post-revolutionary Iran. If Reading Lolita in Tehran is the only book you have read about Iran, you would not be able to imagine that vibrant Iranian women writers such as Shahrnush Parsipur, Simin Behbahani, and Simin Danishvar ever existed, let alone imagine that they wrote during the same period that Nafisi’s book covers. You would not guess that post-revolutionary Iranian cinema has women writers and directors as outspoken as Tahmineh Milani and Rakhshan Bani-Etemad, or that women activists such as the Peace Nobel Laureate Shirin Ebadi spoke and wrote about women and children’s rights during the same period. And these are only a few examples.

Q: In your introduction, you acknowledge that there are gaps in what our information sources tell us about the world. How should we go about filling these gaps?

A: There are many ways, and we can each choose what works for our taste, lifestyle, and background. Meeting people from other parts of the world is always at the top of my list. Of course, the experience of these people will be personal and subjective. But it is also real and heartfelt. By the time you have met the third intelligent and outspoken Iranian woman, you know they cannot be voiceless victims. Reading translated fiction is another very important way to understand a culture. Fiction does not always emphasize facts, but it almost always contains details that bring depth to our perspective and humanize the people depicted in these works. I am delighted to say that more and more fiction (works of Shahrnush Parsipur, Simin Danishvar, Forough Farrokhzad, for example) is translated into English on a regular basis. A third way would be to learn new languages and to travel as much as possible. Learning another language is a means of plugging into a new cultural realm. It is one of the most delightful ways to learn about other cultures, and with the educational tools available in this country, it is doable. As for the news sources, the Internet is becoming a major tool with the presence of news agencies and blogs. Of course, each of these sources would have their particular perspective — some will be the official sites of certain governments. I would say the best way is to alternate between several sources rather than sticking to one regularly. Nothing is more effective than comparing various perspectives.

Q: Jasmine and Stars introduces us to many members of your family, including your uncle, who was both a painter and the head of the personnel office in the Shiraz army. Why did you choose to dedicate your book to him?

A: I have dedicated my previous book, Recite in the Name of the Red Rose, an analysis of 20th century Persian poetry, to my father — my first and best teacher of poetry. My father was as emotional, fussy, and talkative as the poets themselves. Jasmine and Stars, however, is about stars: those who brighten the world by simply existing. Rumi, the celebrated Persian poet of the 13th century said, “If you lose your way in the desert you look at the stars to decide which way to turn. Do the stars speak at all?” His point was that stars teach simply with their presence. That is my uncle the painter; he brightens the lives of those who are around him and shows them the way, often without uttering a word. He is a great painter, yet his greatest artistic achievement is his life. I had to dedicate the book to him.

Q: Why do you think that works that you call the New Orientalist narrative, including Khaled Hosseini‘s The Kite Runner and Reading Lolita in Tehran, are so extraordinarily popular? What kinds of debates have they spurred in the American Muslim community?

A: The works in this category are very different from one another. The Kite Runner, for example, is a more effective story and, at least in parts, shows more depth and nuance than Reading Lolita in Tehran. One would need to look at each of these works independently to be able to provide a more meaningful critique of their appeal to the public. As a category, however, they do share some broad features that explain their popularity to some extent. For example, they are almost always “eyewitness” accounts, which speak to the general public’s curiosity and deep bewilderment about what seems to be going on in that part of the world. These works often do not demand that their reader know a lot of information about the context — the books themselves do away with bothersome details. So, “to know” what is going on, which in reality requires a good deal of discussion about the context, becomes relatively easy. Finally, most of these works appeal to an ongoing post-9/11 sense of insecurity in the reader. They say that the discontented people in the problem-ridden areas in the Middle East are by and large the monsters that you are afraid of. This quick validation of fears brings something of an immediate relief. However, I must say most readers do still feel that these books do not give them the full picture and continue to search for more.

Q: What aspects of Jasmine and Stars do you think readers will find most surprising?

A: I think what is most surprising to the reader would be the humor and the openness of the people I write about. We would hardly see a picture of a smiling Iranian face in the media or hear about their openness to other cultures. When I tell my friends that The Da Vinci Code is a bestseller or that Bill Clinton’s My Life has sold thousands of copies in Persian translation this year, even the people who know something about the rest of the world are surprised. Similarly, people have no idea that in Tehran alone, Iranian Jews worship in over 20 synagogues on a daily basis. These are facts that are simply omitted from the picture.

Q: Your introduction of the Iranian female poet Forough Farrokhzad and the Iranian female author Shahrnush Parsipur are sure to inspire interest in their works. Are the works of both authors widely available in translation?

A: Yes, quite a few of the works of these writers — and those of others like them — are translated into English. We need more translations for sure, but there are already quite a few. It is becoming more and more possible to find out about the works of these writers by doing a Google search on them.

Q: Your feature, “Windows on Iran,” is available on the American Muslim website at www.theamericanmuslim.org. What can visitors to the site expect to find there?

A: I started an e-mail list to keep a relatively small number of friends and colleagues informed about Iran. This was mostly because alarming news — sometimes coming from unknown sources — makes worrisome claims, such as the Iranian government is going to force the Iranian Jews to wear a uniform or the use of foreign words is going to be banned in Iran. I started sending messages to make clarifications about such “news” items. Because art and culture are a great source of information, I included sections on literature, cinema, and paintings in present-day Iran. And because the average American reader does not see many pleasant visual representations of Iran, I added PowerPoint slide shows of cities and of art works. The list grew so large that the computing services department of my university had to turn it into a listserv. Then the web master of American Muslim asked me if they could post it on their site, something I thought was a great idea. We are hoping to archive these windows independently online, which will make them more accessible to the public.

An interview with Fatemeh Keshavarz, author of Jasmine and Stars: Reading More Than Lolita in Tehran (University of North Carolina Press, Spring 2007), was made available by the University of North Carolina Press.

|

| Print