Sunday’s special elections in the German state of Hesse were the first in a year jammed full of state and national votes. The two main results: the right-wing incumbent Ronald Koch won again; and the young party, the Left, again overcame the 5 percent barrier to win six seats in the state legislature.

In the last election, a year ago, Koch and his Christian Democratic Union (CDU) led a campaign featuring racist polemics against young immigrants. The tactic backfired and they took a beating, losing more votes than at any time since 1945. Though still one-tenth of a point ahead of the Social Democrats (SPD), they could not achieve a majority in a legislature split right down the middle, not even with their right-wing ally, the Free Democratic Party (FDP).

The Social Democrats could have formed a government — but only if they had joined not only their traditional friends, the Greens, but also accepted the support of the new Left party and its first six seats — and votes — in the legislature. The leading Social Democrat, the young, vital Andrea Ypsilanti, decided to accept this support, although she had promised during the campaign never ever to ally with the Left. New circumstances forced new thinking, she said. And the Left was willing.

She almost made it. After many months all but one SPD delegate had promised to approve a coalition supported by (but not including) the Left. And all but one were needed. One day before the planned victory, however, three more SPD delegates suddenly held an unexpected press conference. They announced that their consciences prevented them from approving any agreement with the Left, which they equated with all the sins of East Germany. Bitterly disappointed Social Democrats speculated as to what the four might have received to rediscover their consciences. But nothing was proven.

Since neither side could get a majority, a special election was scheduled to clear up the situation. The media attacks against Andrea Ypsilanti became fierce while the national SPD leaders see-sawed on whether to work with the Left or keep viewing it as a pariah. This alienated even more voters.

Sunday’s election was the result, with the SPD in Hesse suffering its worst defeat ever, no great surprise. What was unexpected, however, was that almost no one who had earlier put an X next to the SPD on the ballot switched to Koch’s CDU. Instead, they chose the right-wing FDP or the Greens or stayed home.

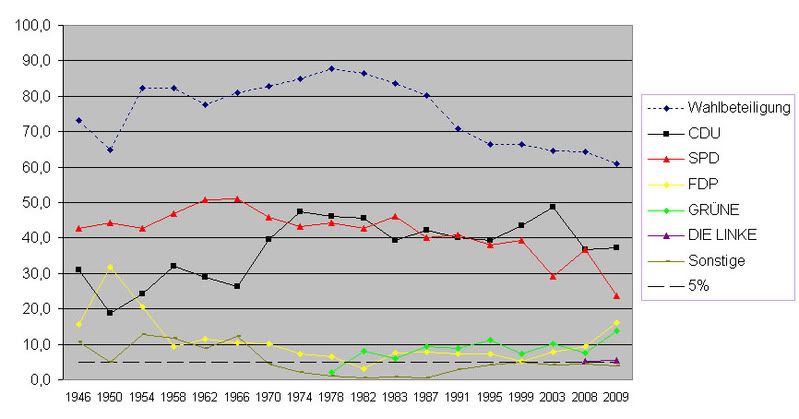

Percentage Change in Vote Distribution in Hesse since 1946

Koch, though as unpopular as ever, now had enough votes to join with the strengthened FDP and form a government, while the SPD licked its wounds, trembling at what was ahead: five more states in East and West Germany will be holding elections, voters will choose delegates to the European Parliament, and the crucial Bundestag elections are due in September. Andrea Ypsilanti, on the moderate left in the SPD, who almost became the only woman leader of a German state, took responsibility for the loss and resigned leadership of the party.

The Left was unable to win many disappointed SPD voters, though it improved its count by three-tenths of a point despite nasty attacks on the party by the press. However, just getting back into a West German legislature was a victory, and it expects much better results later this year. The Left had already shaken up the whole German political scene, turning elections into unpredictable five-party races instead of more or less predictable four-party contests, and its “menace” had also forced all the others to talk more out of the left side of their mouths and even act — albeit to a very small degree — more socially consciously. The Left is now clearly on the all-German map and — if it resolves its own inner problems — can more decisively force German politics to move leftward.

Victor Grossman, American journalist and author, is a resident of East Berlin for many years. He is the author of Crossing the River: A Memoir of the American Left, the Cold War, and Life in East Germany (University of Massachusetts Press, 2003).