|

Decades of increasing poverty, inequality, and insecurity created a powerful backlash against the ruling coalition of the Liberal Democratic Party and Komeito in the 30 August 2009 elections, finally putting an end to Japan’s de facto one-party state. But the backlash only benefited the social liberal Democratic Party of Japan, which increased its seats from 115 to 308 (the DPJ block now enjoys 322 seats, more than a two-thirds majority). The Communist Party and the Social Democratic Party barely hung onto the same numbers of seats that they had before the elections: 9 for the CP1 and 7 for the SDP. On the face of it, it is not a debacle for the Left like those suffered by Communists in India and Italy in the most recent elections. However, one of the items on the DPJ agenda is a plan to eliminate 80 proportional representation seats, and it just so happens that all the Communist representatives are elected to proportional representation seats.

Why did the Japanese Left fail to advance, at a moment when more Japanese than ever appeared to be taking interest in left-wing ideas, as indicated, for instance, by the meteoric rise to bestsellerdom of Kanikosen and the manga based on Capital? Take a look at this video of the 21 August 2009 press conference of JCP Chaiman Shii Kazuo (which comes with English translation), to get a glimpse of how the JCP presented itself to the public.

You’ll see that JCP criticisms of the DPJ agenda2 are to the point, more often than not, but those criticisms don’t quite amount to a compelling vision of a new socialist society that the party should be presenting.3

The strongest point of the JCP criticism of the DPJ is that the DPJ will pay for its promise to expand the social safety net, including the formerly excluded, by increasing the taxes on working-class incomes, leveling down the existing structures of entitlements such as pensions toward the new social minimums, decreasing public works and public-sector jobs,4 and so on. The trade-off is inevitable given the DPJ’s refusal to tax big businesses and capitalists and to cut military spending.

But, in the process of making this point, the JCP ends up defending the old, such as tax exemptions for dependent spouses (usually housewives), which have discouraged many a woman from seeking full-time jobs since wives earning only part-time incomes (roughly up to 1,300,000 yen) are counted as dependents for the purpose of calculating taxes, insurance and pension contributions and benefits, etc. What’s good for working-class families in material terms can be bad for working-class women looking to enhance their gender-bargaining power vis-a-vis men, and the structures of the Japanese welfare state that tacitly assume male family wages, lifetime monogamous marriages, and female spousal dependency are textbook cases of the all too common class-gender contradiction under capitalism. This contradiction is intensifying as more and more Japanese women are clearly losing interest in marriage and childbearing, powerfully demonstrating their sharp rejection of the old gender settlement and silently erecting a strong demographic obstacle to the old methods of restoring economic growth. The JCP, or any other left-wing current in Japan, needs to offer women — and young people in general — a new socialist vision that recognizes women as individuals and fosters new networks of social solidarity based on that recognition, rather than a maternalist Keynesian vision in which women are tacitly assumed to be, or become, or have been wives and mothers.5

The same goes for the JCP’s defense of the Peace Constitution. On one hand, any constitutional revision that the DPJ will put on the agenda is likely to be one that pushes Japan onto the course that Germany took in the process of the dissolution of Yugoslavia, embarking on humanitarian imperialist adventures of its own, not just as a subordinate member of the US-led coalition of the willing. On the other hand, there is nothing democratic, let alone socialist, about defending the constitution that the occupier wrote for Japan, on which the Japanese people have not been allowed to vote. Socialists must present a new democratic vision for Japan. Why not a constitutional assembly in Japan, to write a new constitution as a step toward 21st century socialism?

1 The proportion of the total vote for the Communists, however, registered a slight decline, from 7.25% to 7.03%: see 日本共産党中央委員会常任幹部会 [Standing Executive Committee of the Central Committee of the Japanese Communist Party], “総選挙の結果について” [On the Results of the General Elections], 31 August 2009.

2 For more information about the JCP’s electoral program this year, consult “「国民が主人公」の新しい日本を — 日本共産党の総選挙政策” [Toward a New Japan Where “Citizens Are Protagonists” — the Japanese Communist Party’s General Election Program] (28 July 2009).

3 To begin with, the JCP’s appeal to the electorate called upon them to turn the elections into a referendum on the LDP and Komeito regime first and foremost. That priority automatically gave advantage to the DPJ as the largest opposition party.

4 As pointed out by the JCP, the current number of civil servants per 1,000 of the population in Japan — 32.0 — is already less than half of the US figure of 78.2!

5 It is not that the party is not feminist; it is feminist in its own way. It is committed to gender equality in principle, and it has many policies that would in effect promote gender equality, as well as those that specifically uphold women’s rights. Take, for instance, the party’s policies concerning the question of time, such as decreasing working time to the level where work and family obligations can be made compatible and equally shared by men and women and ensuring that part-time workers obtain the same rights and entitlements as full-time workers; or those that seek to change the character of public employment creation, away from environmentally destructive development projects to expansion of social services. But those are not foregrounded in such a way as to present a powerful vision of a new society that can capture the imagination of people beyond the old party constituencies and contribute to the making of a new hegemony, especially since they coexist uneasily with policy proposals geared toward restoration of economic growth implicitly based on the old Keynesian class-gender settlement.

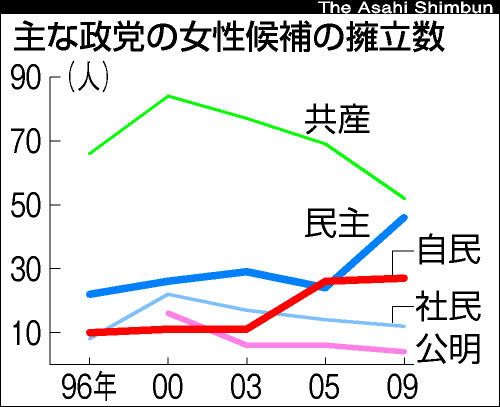

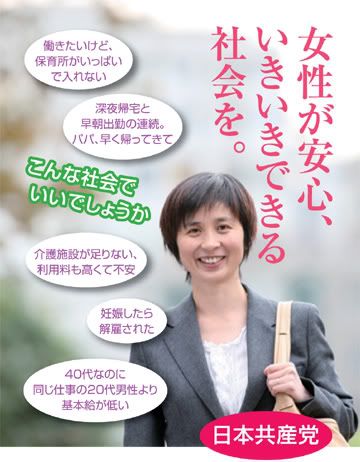

In short, in the public relations department, the JCP’s asset is not turned to its advantage. The JCP and the SDP are the only parties in Japan that have as many women as men stand for elections; and till this year, the JCP had more elected female representatives than any other party, given the strength of JCP women at the local level. You wouldn’t necessarily know that, though, if you just look at the party’s propaganda, from its newspaper to Web site to YouTube videos: e.g., see <www.jcp.or.jp/movie>. And it looks like the party’s once decisive advantage in this area is slipping at the national level, as can be seen in this graph showing the trends of the numbers of female candidates fielded by the five major parties (the green line represents the number of female JCP candidates; the darker blue line is DPJ; the red line, LDP; the lighter blue line, SDP; and the pink line, Komeito).