And so I went to Sardinia, searching for Gramsci’s phantom. An hour’s fight from Rome’s Ciampino took me to Cagliari, Sardinia’s principal city, to its small airport on the island’s southernmost tip. Then I drove a little Mitsubishi rental one-and-a-half hours northwest, chugging along a largely empty central E25 highway, battling a stiff cross wind, onward toward the twelfth century town of Santu Lussurgiu. Santu Lussurgiu is a labyrinth of narrow cobbled streets, many scarcely wider than my tiny car. With a couple of modest supermarkets, a butcher’s store, a few sad, lonely cafés, a population of around 2,500, it felt more like a large village, the sort of place where any strange car, unfamiliar to locals, provoked incredulous stares, as if an alien had landed from another planet.

I’d come excitedly to Santu Lussurgiu. I’d found inexpensive bed and breakfast accommodation in the same building, Sa Murighessa, where a teenage Gramsci lodged during his junior high school years. With its thick stone walls, wooden beamed ceilings, and granite staircase, Sa Murighessa today is one of a group of beautifully renovated buildings belonging to the Antica Dimora de Gruccione, a so-called “albergo diffuso,” a special kind of traditional inn. Room and board are provided in assorted historic buildings scattered around one another (hence diffuse); an old family house typically forms the heart of the albergo’s hospitality, for guests’ meals and collective conviviality.

Sa Murighessa has a plaque on its outside wall, memorializing Gramsci. He himself, though, remembers it as a “miserable pensione.” “When I attended junior high school at Santu Lussurgiu,” he told Tatiana (September 12, 1932), “where three professors quite brazenly made short shrift of Instruction in all five grades, I used to live in a peasant woman’s house (I paid five lira a month for lodgings, bed linen, and the cooking of the very frugal board) whose old mother was a little stupid and forgetful but not crazy and was in fact my housekeeper and who every morning when she saw me again asked me who I was and how it was that I had slept in their house.”

The actual school, Ginnasio Carta-Meloni, at via Giovanni Maria Angioi 109, was a few minutes’ walk away. It no longer exists. These days, it’s a private residence, smartly maintained with an ochre-colored façade, with another brown plaque on the outside wall, announcing “I passi di Gramsci Santu Lussurgiu” [the steps of Antonio Gramsci Santu Lussurgiu], which, in three languages (Italian, Sard, and English), says: “Here was located the Gymnasium Carta-Meloni during Antonio Gramsci’s Studies, 1905-1907.” Underneath is a citation from Prison Notebooks: “culture isn’t having a well-stocked warehouse of news but is the ability that our mind has to understand life, the place we hold there, our relationship with other people. Those who are aware of themselves and of everything, who feel the relationship with all other beings, have culture…So anyone can be cultured, can be a philosopher.”

Gramsci hated his junior high school; they were wretched years, he said. Even as a young lad he could see through his teachers, didn’t respect them, knew their inadequacies. A precocious intelligence was already manifest. In another letter to Tatiana (June 2, 1930), he writes: “one day I saw a strange little animal, like a green grass snake yet with four tiny legs. Locally, the small reptile was known as a scurzone, and in Sardinian dialect curzu means short.” At school, he asked his natural history teacher what the animal was called in Italian and the teacher laughed, saying it was a basilico, a term used for an imaginary animal, something not real. Young Antonio must be mistaken because what he described doesn’t exist. His school chums later made fun of him, too. “You know how angry a boy can get,” he tells Tatiana, “being told he is wrong when he knows instead that he is right when a question of reality is at stake; I think that it is due to this reaction against authority put to the service of self-assured ignorance that I still remember the episode.” He’d already from an early age developed a nose for sniffing out authority put to the service of self-assured ignorance.

Nino had a set routine in those school years, leaving Ghilarza early Monday morning, on a horse-drawn cart, traveling the twelve-miles over the tanca (pastureland) on a dirt track, returning either Friday afternoon or Saturday morning, often on foot. The area could be hairy, bandit and cattle-thief country. Years later he remembered an incident walking with a friend, coming back from school one Saturday morning, plodding along a deserted spot when, all of a sudden, they heard gun shots and stray bullets whistling by. Quickly they realized it was they who were being shot at! The duo scrambled into a ditch for cover, hugging the ground for a long while, until they were sure the coast was clear. “Obviously,” he tells Tatiana, “it was a bunch of fellows out for a laugh, who enjoyed scaring us—some joke, eh! It was pitch dark when we got home, very tired and muddy, and we told nobody what had happened.”

Back then, getting to and from school on foot would have taken Gramsci most of the day, even without being fired upon, and several hours by horse-drawn cart. In more modern times, on Sardinia’s surprisingly smooth, well-maintained country roads, you can zip along the SP15 in a shade over twenty-minutes. Though if you motor too fast, you’ll miss much of what’s noteworthy about the island’s landscape. Not least its stones. John Berger is right when he says that “in the hinterland around Ghilarza, as in many parts of the island, the thing you feel most strongly is the presence of stones.” “Sardinia is first and foremost a place of stones.” “Endless and ageless dry-stone walls separate the tancas,” Berger says, “border the gravel roads, enclose pens for the sheep, or, having fallen apart after centuries of use, suggest ruined labyrinths. Everywhere a stone is touching a stone.” Berger reckons that stones “gave Gramsci or inspired in him his special sense of time and his special patience.” Stones are silently there, stoic and solid, resistant to time, enduring the passage of time, unmoved, knowing that life on earth goes on over the long durée. This notion was surely not lost on its native radical son.

Under a blazingly hot sun, in the lizard-dry countryside before me, I could feel the presence of stones, thick basalt blocks dramatically stacked up one on top of the other, forming the most archaeologically significant feature of Sardinia: nuraghi—tall dry-stone towers, some over forty-feet high. Throughout the island there are around 7,000 nuraghi remaining, important testimonies of Sardinia’s Bronze Age. Nuraghe Losa, on the Abbasanta plateau, a mile or so outside Ghilarza, has an imposing central rectangular keep, surrounded by outer rings of stone walls. It’s now a UNESCO site of world heritage. Other nuraghi, like Nuraghe Zuras, are off the beaten track, along a narrow grassy path off the SP15. I could tell Zuras hadn’t been visited for some time: the grass beside it was over-grown, full of weeds; some giant stone blocks, centuries old, had collapsed; the brown sign, detailing the site’s history, had broken away from its posting and lay upended on the ground.

Like most nuraghi, Zuras has a single entrance, low and narrow, with an interior staircase. Zuras looked so forlorn that I was reluctant to crouch and enter the pitched darkness. What lay inside? An animal’s lair? A bees’ nest? Masses of cobwebs? Snakes? I didn’t fancy finding out. Nobody knows the precise function of nuraghi, excepting that they weren’t, like ancient Egyptian pyramids, burial grounds, places of the dead: nuraghi were very much structures for the living. Most likely they mixed protective and defensive activities, offering shelter to shepherds during inclement weather, and lookout posts for military surveillance; once ascended, they afford dramatic vistas across the whole countryside.

Stones figure prominently in Sardinian imagination and meant a lot to Gramsci; he’d touched many, collected many scattered around the surrounding tanca. At home, he spent hours with a chisel smoothing those stones down, shaping them into pairs of spheres of commensurate sizes, as big as grapefruits and melons, hollowing out little grooves inside each rock. Once ready, he’d insert into the holes pieces of a broom handle he’d cut up, foot-long lengths. He’d then join the spherical stones together, forming homemade, makeshift dumbbells. Gramsci used six stones to make three sets of dumbbells of varying weights, and with them, every morning, as hard as he could, as disciplined as he was, he did exercises to strengthen his weak body—his arms, shoulders, and back muscles, making himself more robust to confront the great and terrible world he knew lay beyond.

***

The Gramscis lived in the center of Ghilarza, at number 57 Corso Umberto I, still the town’s main drag. The house was built in the early nineteenth century, with two floors, divided into six rooms: three on the ground floor, with an inner courtyard, and three on the upper floor. From the age of seven until twenty, Gramsci shared the abode with his mother, father, and six siblings—Gennaro, Grazietta, Emma, Mario, Teresina, and Carlo. In what would become a life of lodgings, hotel rooms, clinics, and prison cells, the Ghilarza house was the only place he’d ever call home, always remember affectionally; a haven he’d return to nostalgically in his prison letters, cherishing it as a site of Gramscian collective memory. The plain, white-walled stone building, with a little upper-floor iron-grilled balcony, is today fittingly preserved as Casa Museo Antonio Gramsci, exhibiting a small yet significant array of Gramsci memorabilia for public viewing.

Months prior, I’d corresponded with the museum to arrange a visit. They’d welcomed me yet said: “the Casa Museo Antonio Gramsci is closed for major restauration works. But you can visit a temporary exhibition in the premises of Piazza Gramsci, right in front of the museum house. The temporary exhibition contains a chronological journey through the life of Gramsci and preserves a large part of the objects, photos, and documents present within the museum itinerary. The exhibition is accompanied by captions in Italian and English…We await your e-mail to plan your visit. See you soon!”

And now I was parking my car along Corso Umberto I, headed for Piazza Gramsci. To the left, looking spick and span, I recognized from photographs Gramsci’s old house; the adjoining properties, at numbers 59 and 61, were covered in plastic sheeting, concealing the building works going on within, the said renovation of the museum complex. Almost opposite, on the other side of the street, I noticed something that would have doubtless thrilled Gramsci: the offices of a small, independent publishing house, a radical Sardinian press whose name sets the tone of its politics: Iskra Edizioni, after Lenin’s fortnightly socialist newspaper, produced in exile in London then smuggled back into Russia where it became an influential underground paper. Iskra Edizioni, founded in Ghilarza in 2000, tries to keep alive Sardinian folk traditions and dialect, and deals with translations of academic books and reissuing of militant texts “that can no longer be found on the market.”

Around the corner is Piazza Gramsci. Two young women welcomed me into the museum’s makeshift store, full of everything Gramsci: tote bags and tee-shirts, posters and notebooks, magazines and books, modestly for sale, all tastefully displayed. Then I was led into two temporary exhibition spaces where, left to myself, I was alone with Gramsci, overwhelmed because he was everywhere. What initially struck was his bed, a little single divan—a very little iron-framed divan, with two walnut wood panels serving as the head and end boards. It was its size, its smallness, that most affected me. If Gramsci slept here until the age of twenty, you get a sense of his diminutive stature—it was like a kid’s bed, not much bigger than a cot.

Nearby, a pewter washbasin and a glass cabinet containing a red and blue plaid shirt, worn by Gramsci in prison, together with toothbrush, comb, shoehorn, and shaving blade. Another glass cabinet had two grapefruit-sized stones, with two little grooves, the remains of Gramsci’s dumbbells, overlaying a series of family photos, Gramsci’s birth certificate, and a telegram Tatiana sent Piero Sraffa, dated April 26, 1937: “GRAMSCI COLPO APOPLETICO GRAVISSIMO, TATIANA.” [“GRAMSCI SUFFERED SERIOUS STROKE, TATIANA”] Above it something even more disturbing: dressed in a dark suit, a photo of Gramsci on his deathbed, taken by Tatiana.

Tatiana did several things for her dead brother-in-law: besides taking care of his notebooks and arranging his burial, she had two-bronze casts made, one of his right hand, his writing hand, the other a death mask, the most haunting object of all the museum’s exhibits. Gramsci looks unrecognizable—bloated, with puffed up round cheeks, far removed from the youthful images of him with flowing locks of curly black hair and those famous rimless spectacles. It was a far cry indeed from how he was remembered at High School: “he may have been deformed,” old school chum Renato Figari recalled, “but he wasn’t ugly. He had a high forehead, with a mass of wavy hair, and behind his prince-nez I remember the bright blue of his eyes, that shining, metallic gaze, which struck you so forcibly.”

Why bloated? It’s hard to say. Poor prison food? Medication for his illnesses? Sedentary life in a cell? Before incarceration, Gramsci was a great walker, covering vast distances on a foot, as a child and adolescent in Sardinia, and as a student in Turin, where he seemed to know old backstreets intimately; and even immediately prior to his arrest, he’d take long strolls around Rome, encountering comrades in cafés, hoofing around town to attend one meeting or another. Yet now I was looking at the cast of a man who’d aged dramatically, gained weight, and looked well beyond his forty-six years. Maybe Tatiana wanted to retain the image of her brother-in-law, whose metallic, piercing gaze was no more. Maybe she wanted to demonstrate to the world what the fascists had done to him. Lest we forget.

It was difficult not to be stirred by the exhibit, not to be affected; but I knew I had one other thing to do in Ghilarza: I had to go and see his mother, whose remains lay on the edge of town in the municipal cemetery. An attractive arched stone entrance led you into a magnificent Cypress tree paradise, aglow in gorgeous late afternoon light. Giuseppina Marcias Gramsci’s grave has a prime site in the cemetery, with little around it, marked by a horizonal marble headstone, still bearing the flowers of the small commemoration of a few weeks earlier, on April 27. A Gramsci citation is chiseled into the foot of the marble, words taken from a letter he’d written his sister Grazietta (December 29, 1930), expressing concern about his mother’s health: “Ha lavorato per noi tutta la vita, sacrificandosi in modo inaudito.” [“She had worked for us all her life, sacrificing herself in unimaginable ways.”] Gramsci’s actual letter continues: “if she had been a different woman who knows what disastrous end we would have come to even as children; perhaps none of us would be alive today.”

Over dinner that evening, back at my albergo, I leafed through a publication I’d picked up during my museum visit, “Mandami tante notizie di Ghilarza.” Its title is a quote from another Gramsci letter to his mother (April 25, 1927): “Send me lots of news about Ghilarza”; a glossy magazine produced by the Fondazione Casa Gramsci Onlus, centering on “Paesaggi gramsciani: il santuario campestre di San Serafino”—“Gramscian Landscapes: The Rural Sanctuary of San Serafino.” San Serafino was one of his favorite boyhood stomping grounds, in a childhood much more adventurous out of school than in, a little village four miles from home, a journey Antonio would have doubtless made on foot.

The village and its chapel overlook Lake Omodeo. The lake runs into River Tirso at the Tirso River Dam and the magazine reproduces a facsimile of a postcard of the “Diga del Tirso” not long after its construction, one Tatiana had sent Gramsci on August 2, 1935, presumably when she was visiting his family in Ghilarza. Three other large-sized facsimiles feature in the magazine, letters Gramsci sent to his mother. One, from October 19, 1931, is worth citing at length:

Dearest mamma, I received your letter of the fourteen and I was very glad to hear that you’ve regained your strength and that you will go for at least a day to the San Serafino festival. When I was a boy, I loved the Tirso valley below San Serafino so much! I would sit hour after hour on a rock to look at the sort of lake the river formed right below the church to watch the waterhens come out of the canebrake and swim toward to the center, and the heaps of fish that were hunting mosquitos. I still remember how I once saw a large snake enter the water and come out soon after with a large eel in its mouth, and how I killed the snake and carried off the eel, which I had to throw away because it had stiffened like a stick and made my hands smell too much.

These lines told me where I needed to head next morning: to San Serafino, to another paesaggi gramsciani. The village was deserted when I pulled up; only a couple of languid dogs greeted me, wandering over unconcerned, not even bothering to bark, showing no signs of malice. They sniffed around me for a while, harmlessly, before lumbering back to where they came from. San Serafino village looked like a small vacation resort, shuttered up, with a series of uniform stone rowhouses, all seemingly unoccupied in non-summer months. The village’s centerpiece is a lovely chapel, pristine and somehow majestic in its understated, white-walled simplicity. In the near distance, below, a picturesque glimpse of Gramsci’s favorite lake. Herein my next mission: get to the lake, try to sit on a rock and look out as Gramsci had looked out.

I went on foot. Crossing a main road bereft of any traffic, the signage reminded me, if I ever needed reminding, that I was in Gramsci country. I took a photo. At the roadside, an old hand-painted sign indicated, in yellow, “Lago,” with an arrow pointing its direction. I followed it, descending a little gravel path. Not a sole in sight. Soon the lake came into view, Lago Omodeo, and finding a rock to sit on at the water’s edge, I wondered whether perhaps I’d discovered Gramsci’s actual rock, where he’d sat for hour upon hour. It was May and baking hot, 100 degrees, without shade. So I knew my visit needed to be brief, imbibing the atmosphere, getting some sense of what Gramsci experienced, of what he’d loved, and what he might have loved again.

***

In truth, I had no real idea what I was searching for, here or anywhere else in Sardinia. I was embarked on a peculiar research project, very unmethodological, impossible to conceive in advance, having little inkling what I’d expect to find, let alone how I would go about trying to find it. And what was this it I sought anyway? I knew that part of it was wanting to see Gramsci’s family house and museum, that I wanted to see some of the more tangible remnants of Gramsci’s Sardinian world, artefacts and documents; but there were other things I was after, too, less tangible aspects of this world, more experiential aspects, things subjective rather than objective, sensory rather than strictly empirical. Or, at least, the sort of empirical that’s hard to qualify and impossible to quantify: a smell, a texturing of the cultural and natural landscape, of Gramsci’s environment, the look on people’s faces, the region’s light and warmth, its dusty aridness, the sun beating down, the sun setting, the sun rising, the faint ripple of the lake below San Serafino, the buzzing of insects, the sound of silence, the presence of stones.

I suppose I was accumulating impressions, and what impressions I’d accumulated I was now trying to recapture on the page back in Rome, where I write, reconstructing my trip from memory, realizing how much of it seemed to pass in a haze. I remember the day after San Serafino, going to Ales—I had to go to Ales (pronounced “Alice”): it was Gramsci’s birthplace, after all, an hour’s south of Ghilarza, a town of 1,500 people that never lets you forget it is his paese natale; it was home only for a matter of months (the family upped sticks shortly after Antonio’s birth to Sorgono, before permanently moving to Ghilarza). Another scorchingly hot afternoon, a fierce sun beating down. God knows how it’s possible that the thermometer could rise even more in July and August. Little wonder Gramsci always felt cold in prison.

There was no shade in Ales, nowhere open, no place to eat, to buy food, to drink anything—and hot, hot, hot. Yet I was there for Gramsci, and it was endearing how much due care and attention Ales devoted to him. His actual birthplace—a two-story, yellow-façade house at Corso Cattedrale, 14—is now a cultural center hosting talks, book launches, and movie-showings, and still keeps the Gramscian red flag flying: one poster in the window read: “STOP ALL EMBARGO CONTRO CUBA.” Gramsci’s life and thought crops up everywhere in Ales, almost on every street corner, by way of a novel series of plaque-posters detailing his lifeline and different aspects of his work. It had all been lovingly curated and presented, and proclaimed Ales as a “laboratorio di idee,” a laboratory of ideas, inviting visitors “conoscere Antonio Gramsci camminando nel suo paese natale”—“to know Antonio Gramsci by walking in his hometown.”

And I did walk, headed for another landmark, another Piazza Gramsci, with its modern stone sculpture garden that looked weather beaten, worn away by the sun, nicely done but utterly deserted by day because of so little shade. As I strolled, by chance I spotted one of the most interesting signs of Gramsci, an impromptu sign, unprogrammed, indicating that the man isn’t only remembered but that he’s also somehow alive in people: graffiti on a rusty old door of an abandoned building, which piqued my attention and brought a smile to my face: “SONO PESSIMISTA CON INTELLIGENZA,” all of which presumably implies that the daubers were somehow optimists of the will—“ottimista per la volontà,” as Gramsci said, summing up my own sentiment about our post-truth world.

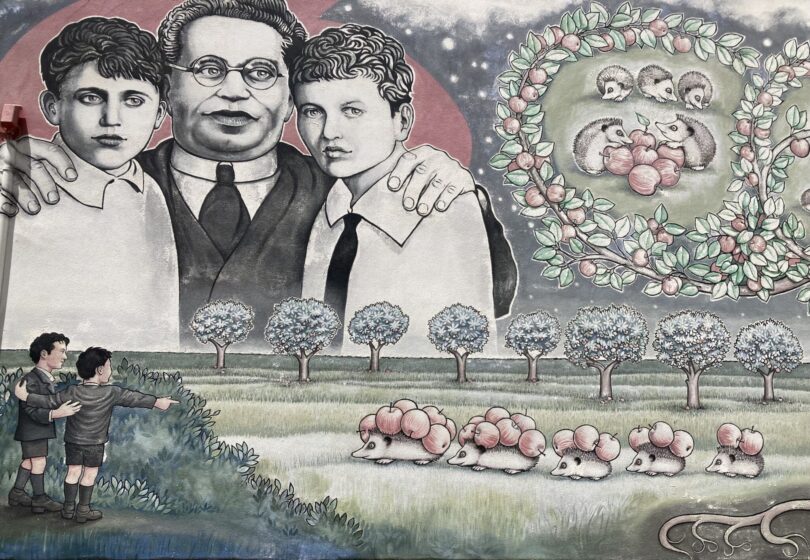

Not far from the graffiti was the loveliest Gramsci homage I’d ever seen, the loveliest and cleverest: a giant mural painted on the side of a whole building, in bright color, huge and stunning, without any trace of desecration, sparklingly clean and vivid. What was so interesting and clever was its blending of reality and fantasy; illustrating some of Gramsci’s childhood adventures with hedgehogs, apples, and snakes; yet also showing him older, smiling, reunited with his two sons, a family portrait, a what might’ve been image if he’d returned to Sardinia, if Delio and Giuliano had somehow made it out of the USSR, come back to Italy to see dad—big ifs. Where was mom Giulia? The mural was so vast that I had a hard time properly capturing it on camera.

To the uninitiated, the hedgehog-apple imagery might be perplexing. For insight let’s invoke a letter (February 22, 1932) from father to son Delio:

One autumn evening when it was already dark, but the moon was shining brightly, I went with another boy, a friend of mine, to a field full of fruit trees, especially apple trees. We hid in a bush, downwind. And there, all of a sudden, hedgehogs popped out, five of them, two larger ones and three tiny ones. In Indian file they moved toward the apple trees, wandered around in the grass and then set to work, helping themselves with their little snouts and legs, they rolled the apples that the wind had shaken from the trees and gathered them together in a small clearing, nicely arranged close together. But obviously the apples lying on the ground were not enough; the largest hedgehog, snout in the air, looked around, picked a tree curved close to the ground and climbed up it, followed by his wife. They settled on a densely laden branch and began to swing rapidly, with brusque jolts, and many more apples fell to the ground. Having gathered these and put them next to the others, all the hedgehogs, both large and small, curled up, with their spines erect, and lay down on the apples that then were stuck to them; some had picked up only a few apples (the small hedgehogs), but father and mother had been able to pierce seven or eight apples each. As they were returning to their den, we jumped out of our hiding place, put the hedgehogs in a small sack and carried them home…I kept them for many months, letting them roam freely in the courtyard, they would hunt for all sorts of small animals…I amused myself by bringing live snakes into the courtyard to see how the hedgehogs would hunt them down.

Ales’ mural offered a beautiful pictorial rendering of Gramsci’s beautiful narrative tale of hedgehogs carrying apples on their backs, gathered together, about to chomp away on their harvested feast. The stars twinkle overhead and a glowing moon gives the whole scene a magical milky charm. Gramsci, aged and portly as he was toward the end, is here radiantly alive, neatly attired in suit and tie, a proud father, arms around his two sons either side of him—a what might have been prospect, a Gramsci family romance, a happier epilogue to the tragic story we know really ensued.

That happy image of Gramsci disturbed me for some time. I remember passing a morning in Santu Lussurgiu, strolling around its old center and then around what’s a sort of small outer suburb, a ring of houses built sometime over the past fifty-years, well after Gramsci’s day. I was deep in thought about Gramsci—not about Gramsci the young lad but Gramsci the older man, the person who might have returned to walk the streets where I was walking. In olden times, Santu Lussurgiu was the site of Sa Carrela è Nanti, a folkloric horse race, a tradition held every Mardi Gras. Horses used to gallop through audience-flocked streets at breakneck speeds, with pairs of riders dressed in flamboyant traditional costumes, donned in obligatory Zoro-like masks. The old town’s walls are still adorned with framed photos of this crazy equine event, now defunct, I looked at some showing the spectacle and its crowds as late as the 1980s.

Perched up on high in Santu Lussurgiu, where you get a sweeping vista of the whole town, is a massive white granite statue of Christ, with placating arms stretched out, and a bright red heart that looks slightly ridiculous, like it’s pulsating, beating for the salvation of the town’s residents. (It resembles Jim Carrey’s heart in The Mask, beating for Cameron Diaz.) I negotiated Santu Lussurgiu’s streets, climbed upward to get a close up of Christ, and witness that panorama before Him. All the while, I tried to visualize Gramsci back here, living in Santu Lussurgiu, imagining his niece Edmea finding Uncle Nino a room, probably near to where he used to lodge, in the old quarter, in a little stone house where various relatives could come and go, cater for his needs, help him recover, regain his strength, his zest for life.

He might have taken short walks in the fresh air, got himself some false teeth, eaten healthily again, found peace and quiet and maybe resumed his work, his letter writing, reconnecting with the outside world, with all the people and places he’d formerly known. Maybe he would have taken the odd aperitivo in town, with his father Francesco, who might have lived himself had his son also lived. Gramsci Sr. and Jr. might have tippled with the town folk; son would have enjoyed speaking their language, their dialect. It could have been right out of the leaves of Machiavelli, of Gramsci’s hero’s life in exile. For downtime, while working on The Prince, Machiavelli loved to sneak through the secret underground passageway of his Chianti wine cellar and pop-up next door at a raucous tavern (L’Albergaccio). He’d guzzle wine, chinwag with peasants and wayfarers, play cards and exchange vulgarities with the butcher, miller, and innkeeper. “Involved in these trifles,” Machiavelli said, “I kept my brain from growing moldy.”

Gramsci’s post-prison life might have been no less bawdy, a homecoming dramatic and heart wrenching, like a scene from Cinema Paradiso—when, after a thirty-year absence, Salvatore, the famous film director, finally returns to his Sicilian native village, attending the funeral of the old cinema projectionist, Alfredo, whom he’d adored as a kid. But maybe Gramsci’s return would’ve been less mawkish; he wasn’t one for fainthearted nostalgia, would have probably been harder, followed the words of the island’s poet laureate, Sebastiano Satta: “His bitter heart lurches./ He does not cry:/ Sardinians should never cry.”

On the other hand, we might wonder how long Gramsci’s convalescence may have lasted before he’d gotten itchy feet, yearned for contact with the wider world again—for engaging politically again. Could he really accept, as he’d hinted to wife Giulia in 1936, “a whole cycle of his life definitively closing”? He’d spent a decade of sedentary life, cut-off from life within four narrow walls; it would be hard to imagine, as a free man, him wanting to sit around all day, behind a desk or in a bar, leading a quiet, mediative and contemplative existence. He’d surely have gotten bored after a while, a country boy who’d tasted the forbidden fruits of cosmopolitanism—in Turin and Vienna, in Moscow and Rome—a roving journalist, activist, and intellectual, a man who’d met Lenin and Victor Serge, who read in different languages, who’d prided himself on his internationalist outlook. Wouldn’t village life have soon become too stifling, too parochial?

Another question we might pose about Gramsci’s return to Sardinia is: did he really plan on staying long? Or was it just easier for him to flee Sardinia than mainland Italy—as he’d apparently told Tatiana, and as she’d written to her sister Eugenia in Moscow? A month prior to Gramsci’s passing, Tatiana told Eugenia (March 25, 1937): “Antonio believes it would be a lot easier to escape from Sardinia than from Italy. We can’t mention it, or rumors will start.” From what would he be fleeing? The Italian fascist authorities? The Russian Communist Party and its apparatchik, suspecting Gramsci as a closet Trotskyite? The Nazis, who’d soon be jack-booting across Europe? And where else might he go?

Gramsci never knew anything about the German bombardment of the Basque town of Guernica; it took place after he’d had his stroke, on April 26, 1937, the day prior to his death. And yet, maybe Gramsci had anticipated a darkening of Europe, was fearing the worst, knew something was brewing, that fascism was not only alive and well but would soon brazenly expand its reach, morph into Nazism? Maybe he feared what was in store for his beloved island should war break out. Mussolini saw Sardinia as a stepping-stone for enlarging his Mediterranean empire. Because of its strategic positioning—only 8 miles from French Corsica—and the importance of Cagliari for launching attacks on Allied shipping in the Mediterranean, Sardinia suffered heavy bombing.

At the same time, the island also had a strong anti-fascist resistance movement, which supported the Allies, and played a significant role in eventual Italian liberation in 1943. If he’d stayed in Sardinia, what role would Gramsci have assumed? A leader of the underground resistance movement? A free man yet a communist enemy of the Nazis, a man who would need to battle on three fronts—against the German Nazis, the Italian fascists, and the Russian Stalinists. Whatever the case, it’s clear his Sardinia peace would have been short-lived, lasting a couple of years only.

On the other hand, would he have opted to join the dissident exodus from mainland Europe? It’s fascinating to consider that the northern Sardinian port of Porto Torres had a direct ferry line to Marseille; from Porto Torres Gramsci could have eloped to the southern French city. Although under German occupation, Marseille’s shady underworld of crime and opportunism, its rowdy bars and back alleys around the Vieux Port, its seafaring and immigrant culture, meant it slipped through the tightening grip of the Gestapo. The city’s cracks offered elicit protection for assorted refugees, dissidents, and Jews, while becoming a wartime waystation for the passage out to the new world. (One of Gramsci’s contemporaries, Walter Benjamin, born 1892, famously didn’t make it out, crossing the Pyrenees from Marseille in September 1940 only to find the Spanish border closed. Stranded, without the right exit visa, he preferred suicide to being sent back, overdosing on morphine in a cheap Portbou hotel.)

Might Gramsci have shacked up with the celebrated artists and intellectuals on the outskirts of Marseille, at the Villa Air Bel, before setting sail in March 1941 on Le Capitaine Paul Lemerle, a converted cargo boat, for Martinique? What a mesmerizing proposition that would have been. Onboard were 350 refugees, as well as a glitterati of creative dissents, castaways of old Europe, including anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, photographer Germaine Krull, surrealist painter Wifredo Lam, the “Pope” of Surrealism himself, André Breton, his wife, the painter-dancer Jacqueline Lamba, together with their six-year-old daughter Aube. The anarcho-Bolshevik revolutionary Victor Serge, himself no stranger to political persecution and imprisonment, was another passenger, accompanied by his twenty-year-old son, Vlady, a budding artist.

Serge and Gramsci were kindred spirits, contemporaries who knew each other in Vienna in the mid-1920s. (There’s a touching photograph of them together, a group shot on a Viennese street, with optimism in the air and a grinning Gramsci.) Serge was remorselessly scathing about people he didn’t like or rate—his Notebooks, 1936-1947 are full of selected character assassinations—yet was generous about those he knew and/or admired, like Gramsci.

A few years after his arrival in Mexico, Serge wrote in his Memoirs of a Revolutionary perhaps the nicest portrait of Gramsci ever written:

Antonio Gramsci was living in Vienna, an industrious and Bohemian exile, late to bed and late to rise, working with the illegal committee of the Italian Communist Party. His head was heavy, his brow high and broad, his lips thin, the whole was carried on a puny, square-shouldered, weak-chested, hunchbacked body. There was grace in the movements of his fine, lanky hands. Gramsci fitted awkwardly into the humdrum of day-to-day existence, losing his way at night in familiar streets, taking the wrong train, indifferent to the comfort of his lodgings and the quality of his meals—but, intellectually, he was absolutely alive. Trained intuitively in the dialectic, quick to uncover falsehood and transfix it with the sting of irony, he viewed the world with exceptional clarity…a frail invalid held in both detestation and respect by Mussolini, Gramsci remained in Rome to carry on the struggle. He was fond of telling stories about his childhood; how he failed his entry into the priesthood, for which his family had marked him out. With short bursts of sardonic laughter, he exposed certain leading figures of fascism with whom he was closely acquainted…a fascist jail kept him outside the operation of those factional struggles whose consequence nearly everywhere was the elimination of the militants of his generation. Our years of darkness were his years of stubborn resistance.

Amid an atmosphere of fugitive uncertainty and fear—fear of being torpedoed or detained by Vichy-controlled Martinique—Serge and Gramsci would’ve had plenty to talk about aboard Le Capitaine Paul Lemerle, plenty of time to argue, to agree and disagree, to agree about disagreeing. Both had the capacity of conviction, believing in the unity of thought, energy, and life, yet were critical of all forms of fanatism. Both knew every idea is subject to revision in the face of new realities. Both would have agreed that the old world was dying and little was left of what they’d known, of what they’d struggled for (Serge’s own title for his memoirs was originally Memories of Vanished Worlds); both knew the new world had yet to be born and monsters lurked in the interregnum, in the darkness at dawn, in the unforgiving years they were each living out. Both would have shared prison tales of hardship and disappointment, told jokes with an inmate gallows humor they knew firsthand.

They’d have likely discussed the relative merits of anarchism and Marxism, agreed about the disasters of Stalinism, found common ground on the need to rebuild socialism through a Constituent Assembly. (In his Notebooks, Serge said socialists “ought to seek influence on the terrain of democracy, in the Constituent Assemblies and elsewhere, accepting compromise in an intransigent spirit.”) They’d have converged and diverged in their views about Georges Sorel, the French political theorist, agreeing about aspects of his anarcho-syndicalism, particularly on the general strike, about its “mythical” nature, that it was a “concrete fantasy” (as Gramsci called it) for arousing and organizing a collective will; yet would have disagreed about Sorel’s ethical repugnance to Jacobinism, which Gramsci recognized as “the categorical embodiment of Machiavelli’s Prince.” The jury would have been out on Gramsci’s feelings about Sorel’s “moral elite,” which Serge liked, the idea that history depends on the caliber of individuals, on how fit and capable they are for making revolution. Maybe Gramsci might have agreed; perhaps this was just another notion of an “organic intellectual”?

After landing in Martinique, where might Gramsci have gone? Followed comrade Serge to Mexico? Taken André Breton’s route, found refuge in New York? They never let Serge into America; no Communist Party member, existant or previous, was ever granted entry; Gramsci would have experienced a similar fate. Mexico would have been the more likely bet. Serge’s weak heart didn’t last long in high-altitude Mexico City: a cardiac arrest struck him down in the back of a cab in 1947. It took several hours before his body was identified. Vlady recalls finding his father on a police station slab. Son noticed the sorry state of dad’s shoes, his soles full of holes, which shocked Vlady because his father had always been so careful about his appearance, even during times of worst deprivation. A few days on, Vlady sketched dad’s hands, which were, as Serge had described Gramsci’s, very beautiful. Not long after, Serge’s final poem was discovered, drafted the day before he’d died, called “Mains”—”Hands”: “What astonishing contact, old man, joins your hands with ours!”

I know, I know–all of this is idle conjecture about Gramsci, maybe even pointless wish-imaging. It didn’t happen. What really happened happened: Gramsci died, never made it out, was never reunited with Serge. While we can act and should speculate on the future, we can’t change the past, the course of a history already done. That past can be falsified, erased and denied, of course, as people in power frequently do—remember Gramsci’s youthful article from Avanti!, penned in 1917, documenting a common bourgeois trait, prevalent today, of renaming old city streets, of coining new names for neighborhoods where a working class past was vivid. “Armed with an encyclopedia and an ax, they proceed to demolish old Turin,” Gramsci wrote of his adopted city. Streets are the common heritage of people,” he said, “of their affections, which united individuals more closely with the bonds of a solidarity of memory.”

So we can’t reinvent Gramsci’s past, shouldn’t reinvent that past. But we might keep his memory alive, find solidarity in that memory, keep him free from any renaming, from the encyclopedia and the ax. His phantom, his death mask, can haunt our present and our future. To remember what happened to him is never to forget his dark times, the dark times that might well threaten us again. Victor Serge recognized this, somehow knew it was his friend’s powerfullest weapon. Twelve-years after their Viennese encounter, “when I emerged from a period of deportation in Russia and arrived in Paris,” Serge writes in Memoirs of a Revolutionary, “I was following a Popular Front demonstration when someone pushed a communist pamphlet into my hand: it contained a picture of Antonio Gramsci, who had died on April 27 of that year.” What should we do with this picture in our own hands? Remember it and pass it on.