Great Britain has known about the Malvinas’ hydrocarbon wealth for decades. The reserves may be worth half a billion dollars.

Great Britain’s interest in the Malvinas’ oil dates back to at least 35 years ago. In 1975, the Crown initiated surveys. Two exploratory missions between 1998 and 2009 eventually demonstrated its potential.

The inclusion of oil in the Malvinas Islands dispute is nothing new. Between 1974 and 1980, the international price of wool — the principal Kelper economic sustenance and the only Kelper export product — suffered a record drop, depressing the islands’ GDP by 25% (Robert Laver, The Falklands/Malvinas Case, 2001). The socioeconomic situation became untenable. Britain then found itself in the dilemma of finally giving in to Argentina’s demands or else attempting an urgent economic diversification and modernization of the islands. The plan was to gradually replace wool by other resources: fisheries in the short term and minerals and hydrocarbons in the medium and long term.

For the purpose of discovering a natural wealth replacement in the archipelago, critical to the success of the plan, Britain sent missions to the islands, each of which was made up of parliamentarians, geologists, and military men, between 1975 and 1976. The results were encouraging. The strategy of economic modernization — key to retaining the islands under the dominion of the Crown — implicitly meant including the population of the islands in the negotiating table with Argentina, in violation of UN Resolution 2065, since the main stakeholders in the exploitation of these new resources would be the Kelpers. Thirty-five years later, the British plan for socioeconomic modernization of the islands is one step away from becoming reality.

That there is oil in the Malvinas is no surprise to anyone. However, how much oil there is remains a question. For that, the key question turns out to be the minimum price of a barrel of oil that makes commercial exploitation viable and the type of crude available for extraction. What is the threshold price and what is the quality of the crude? Below the international price of $25 per barrel, according to the operators themselves (Rockhopper-Interim Report, 2008), the Malvinas oil extraction will be unviable. Today oil is trading at $77 a barrel, and all projections indicate that the prices will remain thereabout or even rise in coming years.

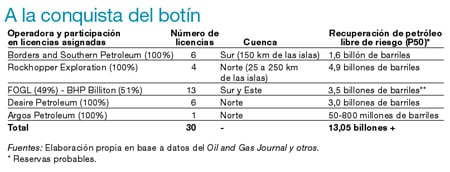

In terms of quality — and in principle only for the North Basin of the Malvinas — the Shell well 14/10-1 drilled in 1998 proved the existence of medium crude of 27 º API (North Falkland Basin-Desire Report, 2009 ). After the acquisition of these data, the first exploratory phase of 1998-2001 was initiated, with the participation of Shell, Amerada Hess, Lasmo, Lundin, the British Geological Survey, and the United States Geological Survey. The second exploratory phase of 2001-2009 counted on British companies Borders & Southern Petroleum, Rockhopper Exploration, Desire Petroleum, Arcadia Petroleum, and Argus Petroleum. Now, Australia’s BHP Billiton and the Kelpers’ own Falkland Oil and Gas Limited (FOGL) are preparing to step into the ultimate exploratory phase, one that will eventually confirm the Malvinas’ oil potential and inaugurate the much prized extractive phase.

According to estimates by the same operators, the offshore petroleum potential of the islands would be a minimum of 6.525 billion barrels of oil. If these probable reserves — equivalent to about US$502.425 million at $77 per barrel, yesterday’s price — are proven, the Malvinas oil will be more than three times the proven reserves of our country as of December 2008 (1.987 billion barrels, according to the Energy Ministry of Argentina).

Meanwhile, the contracts for the tendered areas have benefited the Kelper government for many years: $30,000 per year in taxes before the discovery. Upon the discovery of oil (with the reserves proven and the extraction stage initiated), the island government will charge the operators some $375,000 per year/production area, a 21% corporate tax (which will rise to 26% after a contract year), and a 9% royalty on the total extracted.

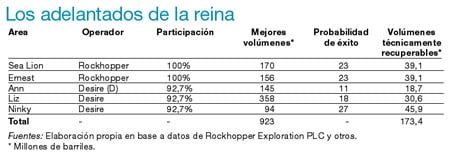

The total offshore exploratory potential of the Malvinas consists of a surface area of four sedimentary basins around it. The total area of the four basins amounts to approximately 400,000 km2, more than thirty times the size of the Gran Malvina and Soledad Islands together, almost two and a half times the province of Córdoba, and 50% larger than the British North Sea oilfields. Of the four basins, the most cost-effective (due to its low depths and proximity to the islands), as well as in possession of the largest amount of potential oil (3.900 billion barrels, 60% of the estimated volumes on the way to being certified), is the so-called North Basin. This basin covers an area 50 kilometers wide and 230 kilometers long. The south and east basins, while promising, are at greater depths and the tendered areas closest to the islands are located a little less than 150 kilometers away (as opposed to about 25 km in the case of the North Basin).

Why so far away? Is it just due to a geological issue? As confirmed to this author by the islands’ director of mineral resources, Phyll Rendell, in 2004, a sort of exclusion zone has been created south of the islands, where any drilling is forbidden. The reason is simple: in that area lie British shipwrecks that are believed to contain nuclear war material.

To the Conquest of the Booty The Queen’s Viceroys  |

Among the principal oil operators in the Malvinas is Desire Petroleum (1996), whose founder, Labor MP Colin Phipps, participated in one of the aforementioned mid-70s missions with the aim of finding a natural wealth substitute in the archipelago. Colin died in 2009, and his son Stephen, age 52, took charge of the company with 13.38% of the equity. Former broker at the London and New York Stock Exchanges, Stephen says that his father attended the Cabinet meeting where Margaret Thatcher decided to declare war on Argentina (WalesOnline-UK News, 3 December 2009).

With the third-generation semi-submersible rig Ocean Guardian contracted by Desire for this final stage, the first wells are slated to be drilled in the area named Liz (92.5% Desire and 7.5% Rockhopper), and then the drilling will proceed under the Rockhopper operation in the Sea Lion and Ernest areas. Depending on the results, the operation will continue in the remaining fifteen areas of the North Basin. Technically recoverable volumes to be confirmed in the coming months may amount to the volume of crude that Argentina extracts in eight months.

The beginning of this final exploratory phase has, for Argentina (and UNASUR), not only geopolitical (a military base of a foreign power on national territory) and political (the only 21st-century colonial enclave in action) implications, but also fundamentally economic (the probable reserves on the islands equivalent to about US$502.425 million) and energy (if these reserves are proven, the lifespan of Argentina’s proven reserves would extend from 6-7 years to about 27 years) ones. The British initiative greatly harms the economic and energy national security of Argentina.

The original article “Tras un manto de sospechas y especulaciones” was published by Página/12 on 18 February 2010. Translation by Yoshie Furuhashi (@yoshiefuruhashi | yoshie.furuhashi [at] gmail.com).

|

| Print