The Fifth Five-Year Plan of the Islamic Republic of Iran (1389-93, 2010-14), still under review by the parliament, has a clear goal for reducing inequality in five years — a Gini index of 0.35 for income. This is a substantial reduction from the high level of inequality that has plagued Iran in recent years. The law for targeting of subsidies, which was passed last January but is still in limbo, is the main instrument for reaching this target. It aims to raise prices of energy products to world prices during the plan period and redistribute half of the proceeds to lower income households. How radical would the redistribution have to be for the government to reach its inequality goal?

To answer this question properly one would need a serious modeling exercise, but a little play with numbers is enough to give us an idea of the potential of the targeting law to create a more equal distribution of income. I also recognize that the premise of the exercise — plans and their targets — may be too optimistic. President Ahmadinejad is not a big fan of planning — in 2007 he dissolved the 60-year-old Management and Plan Organization — and the last plan missed its targets by wide margins. The Fourth Plan aimed at 8 percent annual growth, 9% inflation, and 7 percent unemployment, but only got 5 percent growth, 15 percent inflation, and 11 percent unemployment.

Those goals were not reached perhaps because they were too ambitious. Is a Gini index of 0.35 an ambitious goal for income inequality? Yes and no. Yes, because Iran has historically had high levels of inequality. No, because this is the level of income equality that Iran’s neighbors enjoy; Egypt, India, Pakistan, and Turkey, all have Gini indices about or below 0.35. In the 1970s, inequality in Iran reached Latin American levels and the Gini index was above 0.50; revolutionary redistribution in the 1980s brought it down, to around 0.40-0.45, where it was before the oil boom of the 1970s and where it has stayed in the last twenty years (see my article for a review of this evidence). Iranian inequality has moved up and down with oil prices, but has been remarkably resilient to changes in policy from Rafsanjani to Khatami to Ahmadinejad — so far at least. To lower the Gini index to 0.35 would be a first in Iran’s recent history and a serious challenge. Can the targeting of subsidies do what the Rafsanjani and Khatami administrations failed to do? The answer I propose here is yes, technically speaking, but. . . .

A Simple Simulation

To demonstrate the yes part, I will simulate the targeting of subsidies using the 2007 round of the Household Expenditures and Income Survey collected by Iran’s Statistical Center. Inequality, as measured by per capita expenditures, was rather high in 2007 (Gini=0.44), but came down somewhat in 2008, mainly because of the recession. It turns out that even for a high inequality year such as 2007 redistributing the subsidy for just three of the four items that I listed in a previous post could bring down the Gini index to 0.35.

Here is how my simple simulation works: the revenues saved from subsidies for gasoline, natural gas, and electricity in 2007, about 130 trillion rials ($13 billion), is distributed equally among individuals below the median per capita expenditures (pce). To obtain the simulated pce after redistribution, I first subtract the actual amount of direct subsidies from the pce of all individuals, and then, for those below the median pce, I add back an equal share of the saved $13 billion. How it should work is a lot more complicated and, as I said earlier, requires serious modeling. In reality, when subsidies are reduced expenditures go up, not down as I have assumed here. Furthermore, changes in relative prices cause consumers to make substitutions, ending up with a different basket than they started with, again unlike what I assume here. But, in the end their real expenditures will fall, just as I assume here, albeit by less than the amount of the subsidy because of the substitutions.

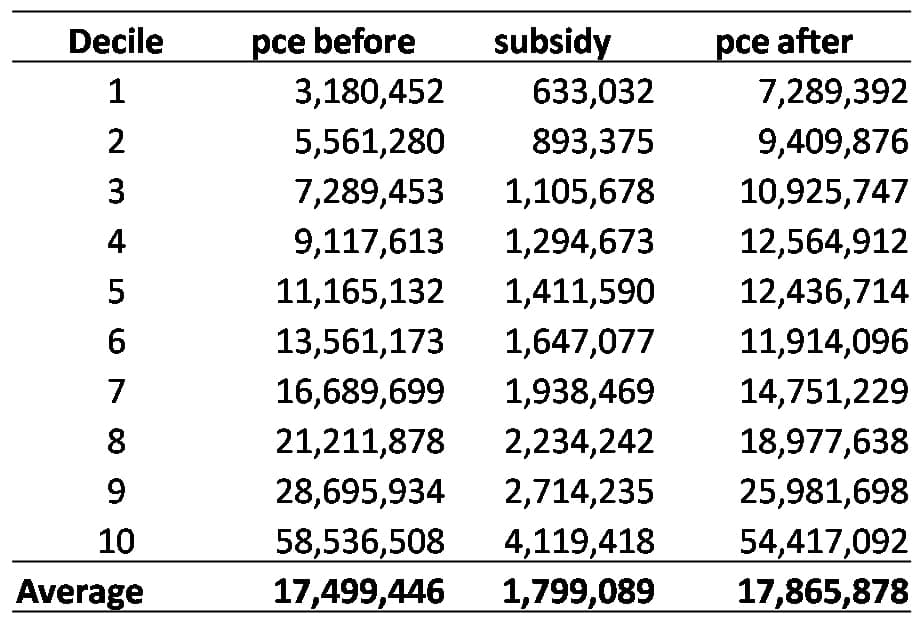

The table below shows the actual 2007 pce (pce before), the subsidy per person from these three items, and the simulated pce after redistribution (all in 2007 rials per year). The assumptions behind the level of the subsidy are as in my previous post on this subject (four times the actual price).

Notes: All numbers are 2007 rials per person per year.

Source: Author’s calculations, Household Expenditure and Income Survey, 2007, Statistical Center of Iran.

Notice that the average person in the 6th decile, which will not get cash back according to my scheme, will become worse off than the average person in the fourth decile! The distributions that result from the pce before and pce after are quite different, and the Gini index falls from 0.44 before to 0.35 after redistribution. The large drop in the index is an indication of the size and the regressive nature of Iran’s energy subsidies. The figure below depicts the Lorenz curves for before and after redistribution:

Note: The Lorenz curve shows the share of the lowest x percent of the population in total expenditures. The ratio of the area between the curve and the line of perfect inequality to the lower triangle is the Gini index.

As expected, the Lorenz curve for the simulated pce (with redistribution) falls inside the curve for the actual pce. (The Gini numbers indicate that the area between the two curves is 9 percent of the area of the triangle under the line of perfect equality.)

But . . .

Solving Iran’s inequality problem by targeting subsidies is easy on my computer but not in the real world. There are three problems. First, as the fiasco of the classification system with “branches” demonstrates, about which I wrote briefly in a previous post, finding who is above and who is below the median income is fraught with complications. There is a new director at the Statistical Center of Iran, which championed the scheme, so perhaps there is some rethinking of using household data to tell who’s got what.

Second, my calculations assume that the refund money is distributed to individuals not families, which in practice is not easy to do. In all likelihood, the government will give the money to the head of the household, which in Iran is defined as the male breadwinner unless none is present. In most households the head — male or female — would probably do the right thing, and distribute the money in a fashion that would serve the needs of its weaker members as well, but not in all families. The danger is that, in the poorer families (especially those with drug addicts), children and women would benefit little, undermining the goal of equity. There is a lot to learn about these conjectures from survey data, but I have not come across any.

Third, and most important, cash-back programs tend to be short-term fixes for deeper problems of inequality — such as poor incentives for investment in human capital and inequality of opportunity. Mexico’s cash-for-enrollment Progresa/Oportunidades program is an example of a successful program that has improved incentives for the poor. There is nothing in the current version of Iran’s targeting legislation that aims to improve incentives or level the playing field.

The cash rebate part of the existing targeting law could be designed to address some of these issues, by giving the money, for example, to mothers (incentives) or investing the funds in health and education services in poorer neighborhoods (level the playing field). Post-revolution Iran is known for success in the delivery of basic services such as electricity, health, and education to poorer areas that have done much to level the playing field. Young rural women are no longer saddled, as they were a generation ago, with heavy child-bearing and child-rearing duties that used to set them on a separate path in their human development compared to their urban counterparts. (You can read more of my writings on these issues here, here, and here). These investments have produced impressive reductions in poverty since the 1980s, though their impact on equity is yet to be seen. To reach greater equity much more work is needed in leveling the playing field. There is work to be done for greater equality of opportunity in education; access to quality schools, especially above the primary level, and access to private tutoring, which now seems necessary for securing a coveted position in a good university, are far from equal. Would anyone seriously argue that the money invested in these services would have been better spent as direct handouts? Cash assistance programs have been important in reducing suffering, but they are not the reason why rural women and children are healthier and better educated.

Djavad Salehi-Isfahani is a Dubai Initiative research fellow at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard University. This article was first published in his blog Tyranny of Numbers on 31 March 2010; it is reproduced here for non-profit educational purposes.

|

| Print