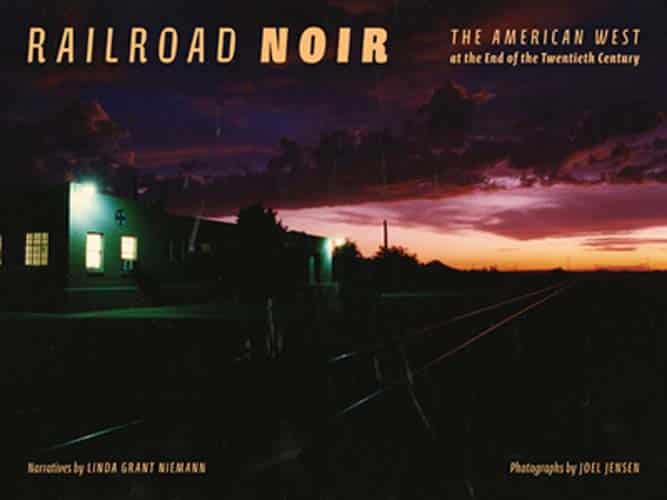

Linda Grant Niemann. Railroad Noir: The American West at the End of the Twentieth Century. Photographs by Joel Jensen. Indiana University Press, 2010. Pp. 168. ISBN-13: 978-0-253-35446-4.

Linda Niemann worked for twenty years as a railroad brakeman in the western US. I have worked for twenty years in a railroad diesel shop in the eastern US. Linda’s job, once she went booming, took her over hundreds of miles of territory in the west, from Southern California to South Texas. My shop job kept me in one yard, wearing a groove into the highway from home to work. Linda often lived out of motels or the back of her pickup. I have always been able to sleep at home at night. So as far as railroading goes, our experiences are about as far apart as they can be in one industry.

Linda Niemann worked for twenty years as a railroad brakeman in the western US. I have worked for twenty years in a railroad diesel shop in the eastern US. Linda’s job, once she went booming, took her over hundreds of miles of territory in the west, from Southern California to South Texas. My shop job kept me in one yard, wearing a groove into the highway from home to work. Linda often lived out of motels or the back of her pickup. I have always been able to sleep at home at night. So as far as railroading goes, our experiences are about as far apart as they can be in one industry.

Nonetheless, certain aspects of the life are universal. The camaraderie born of working in a hidden world of work, the “giant in the background” of America, at once covered with romantic lore of the lonesome whistle across the plains, while at the same time made up of a gritty reality of dirty relentless jobs with shifts that make a 9-to-5 schedule impossible. Never mind having Saturdays and Sundays off. Transportation railroaders live by a phone that can ring at any time, shop workers can count on years of shift work with days off during the week.

So while I have not known the wide open spaces Linda has seen in her railroad travels — so unlike some of the claustrophobic shop jobs like working under a locomotive changing inside brake shoes — I can share in the delights of the secret handshake language of railroading that makes a glossary essential to Linda’s books.

Don’t be put off by having to learn the railroad lingo in Noir though. Linda Niemann, now a professor of literature in Georgia, got her PhD before she started railroading and this book is full of the pungent evocative prose that made her first book, Boomer, such a treat, even a cult object.

Here she is in Texas:

One day I was called for a hauler to Galveston and saw the Gulf of Mexico for the first time. The hoghead had asked me to run and I sat in his seat, kept the throttle on 3, and opened the window to the offshore breeze sweeping the causeway as we walked on water, rocking toward the island, owning the way. Yarding the train there, we sunk into the sand, the rotting ties hardly held by spikes, the cars leaning so much we nearly cornered the engine getting around them on an adjacent rail. The placed smelled like the sea, but humid and decayed. The oily smell of the Gulf seeped through the sand, coating everything.

Yet a PhD in literature does not get in the way when slinging rails talk, for example:

Meanwhile I’d watch the shove down to John at the industry, to see that we didn’t run over any commuters on the platform. He’d make the hook, ride the rear car out, and peel off to take the shove on the main. We’d leave our pulls on the main, John would ride the point with the spot cars inside, and I would hang the marker on the rear car and go back the main line switch to watch the shove out. John would peel off the last car at the gate, close up, and sprint over to the main to make the couple. I’d send him the cars, close the derail, and report us to the dispatcher as traveling east back to the yard — after our air test, of course.

Got that all ye that park the car in the mall Saturdays???

I should mention that this is a real coffee table book, with beautiful photos by Joel Jensen interspersed between Linda’s stories. Jensen’s photos look like he still uses film, slightly granular, with lots of shots of railroading at evening, suiting very much the “noir” theme of the book.

“Noir” also is a theme for Linda personally. This book picks up where Boomer left off, she is no longer a “baby” rail except for seniority, and she documents the dark decline in the switchman’s craft as the Southern Pacific is taken over by Union Pacific, radios and remote control make their appearance and teamwork is replaced by technology supervised by an increasingly autocratic management.

As in Boomer Linda does not flinch from both the good and bad in her personal life as a rail. Relationships come and go; she takes time to learn another language and culture, Spanish and Mexican; and finally she is driven out of the railroad life by a bout of breast cancer.

In the railroad shop I’ve seen steel brake shoes weighing 30 lbs replaced by composites, mechanical linkage replaced by electronic fuel injection, and 26L mechanical air brake systems replaced by computerized electro-mechanical systems. Not that I am nostalgic for those immense brake shoes for billy goat switchers, or for hoisting in place 26L control valves, jobs that used to take two people. But we must recognized that capitalism constantly seeks to replace human labor with machines and the work force shrinks a little more with each technical rollout without necessarily any payoff for the worker.

On the transportation side, 10 years after she ended her railroad career, Linda Niemann ends her book with interviews with railroaders working today, often alone with a remote control on their belt, and wonders where this brave new world takes us, when we are talking about moving thousands of tons on steel wheels thousands of miles every day. In her twenty years of western railroading she lived through much of the changes and she sees what has been lost in human terms and in terms of skill and craft.

She says, “The twenty year gap in hiring is now a chicken coming home to roost. When I left the railroad in 1999, they were just hiring new people. Now the old heads are going, going, gone. There is no one to teach the craft and the craft is being deskilled. No getting on and off moving equipment. No drops or other skilled moves requiring teamwork.”

Someday all of us as a society will have to confront the questions she lived on the rails: what is the price, the real price of progress under capitalism? Can we all live with working alone with a computer or a remote control? And can we really live, or just survive? Or can we even survive?

Railroad Noir poses these questions in the context of railroading, with vivid elegant prose accompanied by Joel Jensen’s starkly dramatic color photography. It’s a book that should be read by a bigger public than the world of rail.

|

Jon Flanders is a member and former president of IAM LL 1145 and a member of the Troy Area Labor Council, AFL-CIO. |

| Print