For many weeks now, the historic social change sweeping across France has drawn increasing attention globally. It should. A genuine, mass democratic upsurge has surprised all those who thought, hoped, or feared that such things could no longer happen in countries like France or the US. Millions of French people — in left political parties, church, and student groups — have accepted and cheered on the leadership of a unified trade union movement. They have recomposed and reinserted a powerful left into French politics. They are profoundly challenging President Sarkozy, his conservative political allies in both houses of the French legislature, and the entire twenty-five-year neo-liberal drift of economics and politics in France. Along the way, they have demonstrated a strength and cohesion that renders the existing French right an annoying small noise in comparison.

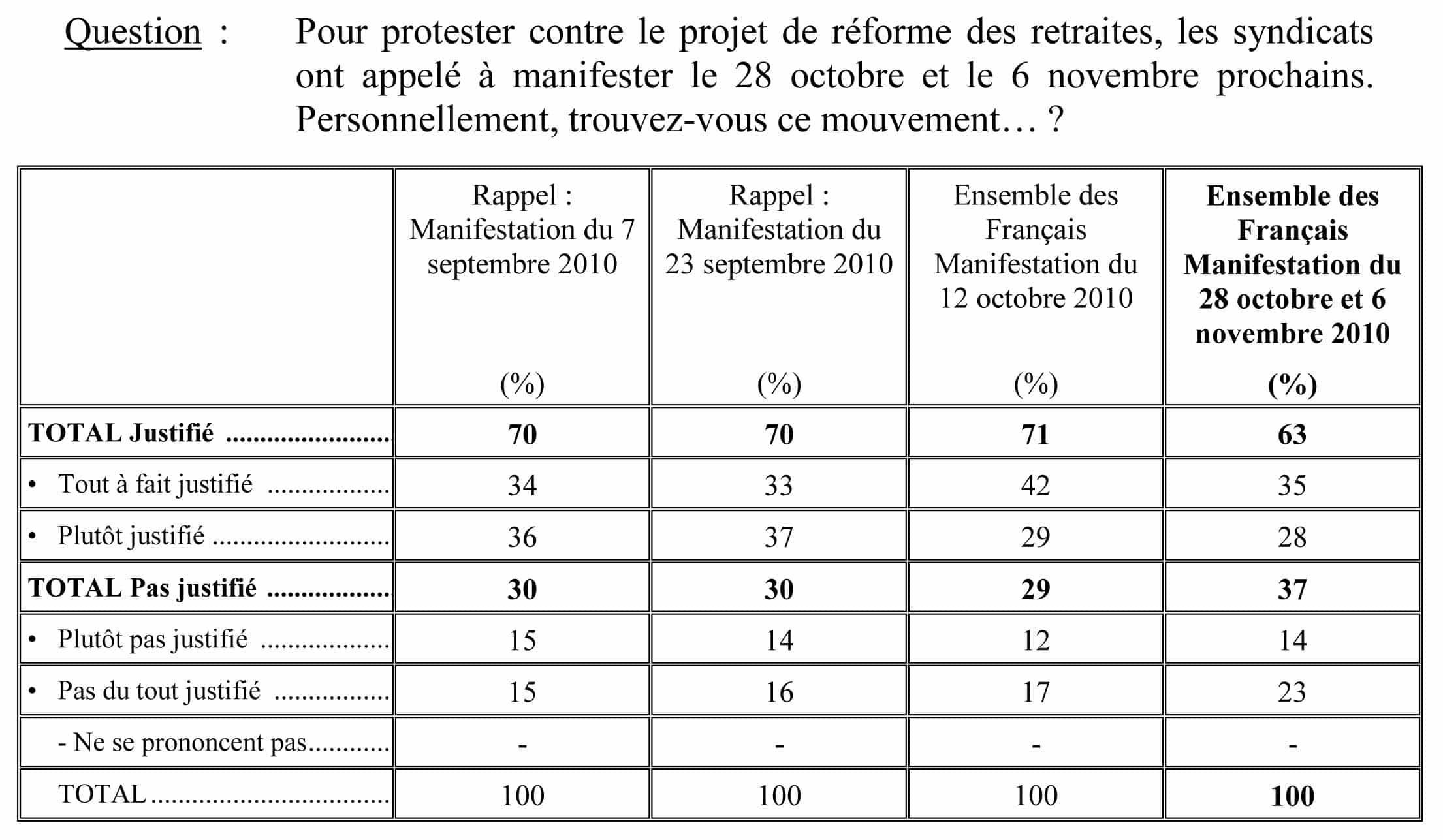

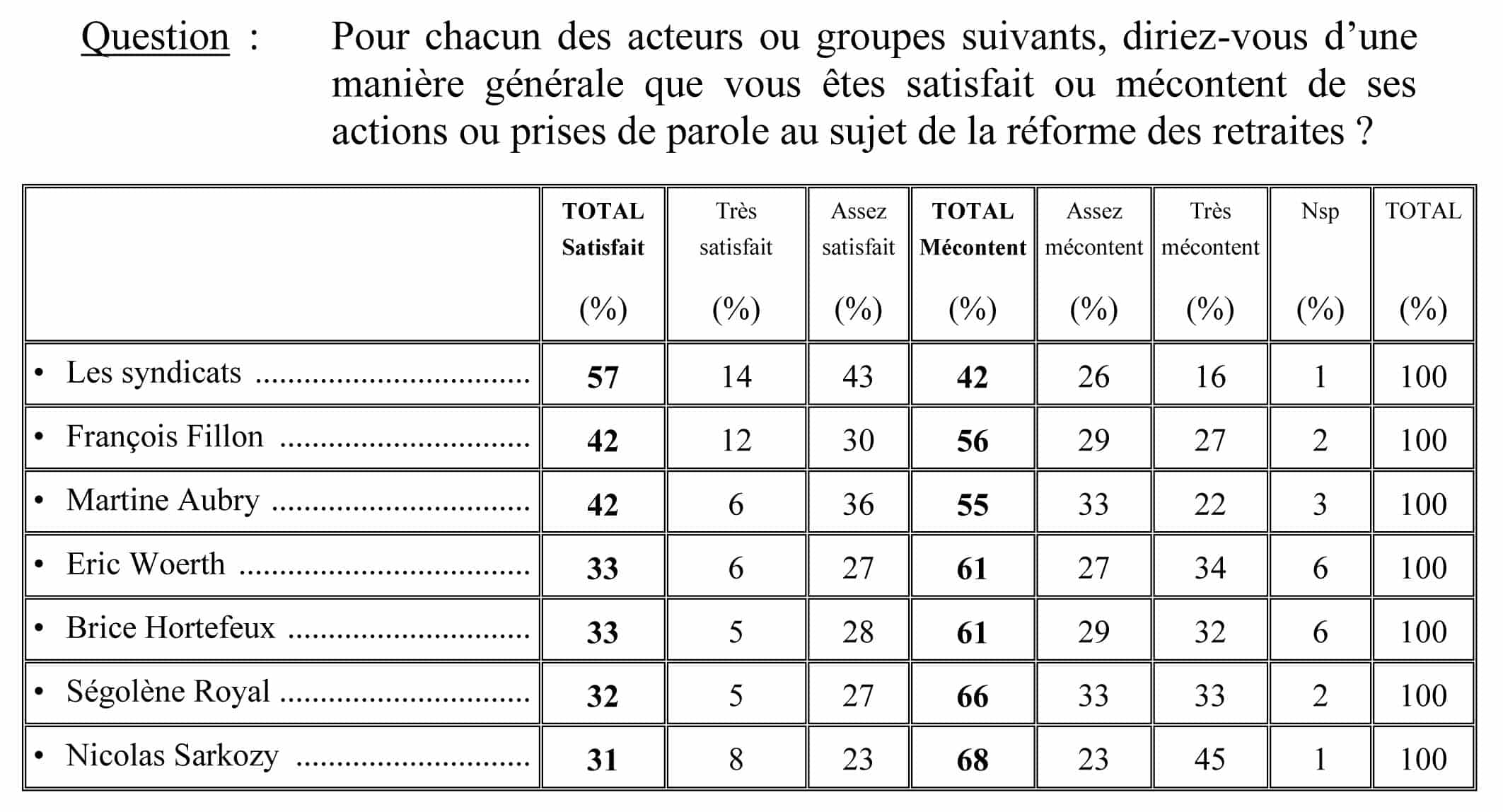

“To protest against the retirement reform, the trade unions have called demonstrations on 28 October and 6 November. Personally, do you find this movement is . . .” (justifié: justified; pas justifié: not justified) Source: “Les Français, la réforme des retraites et le mouvement de protestation: Résultats détaillés” (Ifop, 25 October 2010). “Regarding each of the following actors or groups, would you say, generally, that you are satisfied or dissatisfied with their actions or statements on the issue of retirement reform?” (satisfait: satisfied; mécontent: dissatisfied)  Source: “La satisfaction à l’égard des acteurs impliqués dans la réforme des retraites” (Ifop, 25 October 2010) |

Depending on who counts, the French left has repeatedly mobilized between 1.3 and 2.9 million people into action in over 240 cities and towns across the country. Given that the US has five times the total population of France, the equivalent mass mobilization in the US would entail between 6.5 and 14.4 million. No political movement in US history has so far come close to such numbers of mobilized, active participants. This truly mass mobilization in France began with the general strike on September 7. That action garnered a public opinion poll of 70 per cent either “supporting” or “sympathetic to” the strike movement. That level of public opinion favoring the French strikers and demonstrators has held constant to this day despite escalating government and corporate threats, intimidations, and a defiant Sarkozy’s barking about never compromising. France’s “silent majority” is no longer quiet, thereby exposing the regime as a minority in power that seeks to maintain and exploit its self-serving political and economic positions.

The tension mounts with each passing week. So do the stakes. Behind the intense dispute over details of retirement eligibility, the government’s austerity program, etc., there looms the more basic question of whether France’s majority will continue to absorb the instabilities, inefficiencies, immense costs, and injustice of the country’s capitalist economic system.

The relevance of all this to everyone in this country should be clear. Average working people in the US have suffered since the crisis began in 2007 much as their French counterparts did; indeed, it hit harder here than there. The same issues that concern the French (unemployment, precarious jobs, declining benefits, huge government bailouts of the rich and well-connected, etc.) likewise agitate most people here. France’s experience suggests the potential in other countries for the parallel emergence there of huge left movements opposing policies that burden average citizens with the costs of capitalism’s crisis and of bailouts rewarding the same enterprises that contributed to the crisis. France today suggests that when you further push a population to suffer reduced public payrolls and thus government services (in “austerity” programs to pay for overcoming the crisis), you risk provoking a mass left upheaval into the political, cultural, and ideological life of a country. France will not be the same in the future, no matter how this crisis ends.

The French strikes and demonstrations are coalescing around some basic demands that go far beyond the rejection of Sarkozy’s demand for a two-year postponement of retirements for French workers. Contrary to so many US media reports, that particular issue was never what brought out millions of demonstrators and strikers; that was the bare tip of an iceberg. The issue that mobilizes the French is the basic question of who is to pay for (1) the collapse of global capitalism in 2008 and 2009, (2) the ongoing social and personal costs of high unemployment, loss of homes, reduction of job benefits, and the general assault on most citizens’ standards of living, and (3) the costs of ending the crisis. The French masses have already absorbed and suffered the costs of (1) and (2). They have drawn the line at (3). That they now refuse.

Instead, they demand that the costs of fixing capitalism’s crisis be borne chiefly by taxes on the banks, large corporations, and the wealthy. Those groups are declared to be (1) those most able to pay, (2) those who benefited most from speculations and stock market booms before the crisis began in 2007, (3) those whose investment and business activities were key causes of the crisis, and (4) those who got the biggest, earliest bailouts from governments subservient to them. As the Sarkozy government becomes increasingly isolated and reviled, the French capitalist elite — known there as the “patronat” — must begin to worry. That elite wants Sarkozy to preside effectively over a peaceful, docile, and profitable France, not one convulsed by such powerful oppositions. For them, he is not doing his job well.

Meanwhile, French workers re-learn — and remind everyone else — that, without their work, the economy stops. Corporate executives and politicians bark orders, but nothing happens unless and until workers comply. In their solidarity, the French rediscover the taproots of their political power. And their rediscovery ramifies everywhere, including among US workers, students, and others eager for a mass movement against capitalism’s crisis and the social costs it imposes. US citizens are seeking ways to articulate an attractive left economic and political criticism of the crisis and of the government’s response, and they are seeking a left alternative program to propose. France matters because it suggests a concrete form and substance for what such US citizens seek. Perhaps the best way to undercut the appeal and influence of the Tea Party Right in the US would be, as in France, the upsurge of a comparable left alternative.

Richard D. Wolff is a Professor Emeritus at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst and also a Visiting Professor at the Graduate Program in International Affairs of the New School University in New York. He is the author of New Departures in Marxian Theory (Routledge, 2006) among many other publications. Check out Richard D. Wolff’s documentary film on the current economic crisis, Capitalism Hits the Fan, at www.capitalismhitsthefan.com. Visit Wolff’s Web site at www.rdwolff.com, and order a copy of his new book Capitalism Hits the Fan: The Global Economic Meltdown and What to Do about It.

| Print