Introduction

Many policymakers and analysts are arguing that there is an urgent need to make changes to Social Security. They point out that the projections from the Congressional Budget Office and the Social Security Trustees show the program to be out of balance in the long-term, therefore we would be best advised to make changes as soon as possible. It is argued that this will both make the necessary changes easier and also will provide confidence to financial markets that the country can deal with major problems.

While it is understandable that those seeking to cut Social Security benefits and/or privatize the program would push for quick action, it is difficult to understand why supporters of the existing Social Security system would take this view. There is enormous public confusion (much of it deliberately cultivated) about the extent of the program’s projected shortfall. This makes it far more likely that any changes to the program in the current environment will involve more cuts than would take place among a better-informed electorate.

This paper argues that supporters of the existing Social Security system should try to ensure that no major changes to the core program are implemented in the immediate future. It points out that:

- There is good reason for believing that the public will be better informed about the financial state of Social Security in the future, in part because of the weakening of some of the main sources of misinformation;

- Many more people will be directly dependent on Social Security in the near future. These people and their families will likely be strong defenders of the program;

- The group of near retirees, who may be the victims of early action, will desperately need their Social Security since they have seen much of their wealth eliminated with the collapse of the housing bubble; and

- The concern over “maintaining the confidence of financial markets” is an empty claim that can be used to justify almost any policy.

Keeping Fear Alive: The Effort to Undermine Confidence in Social Security

Polls consistently show that a large majority of working age people does not expect to be able to collect Social Security benefits.1 They have been led to believe that the program is hugely out of balance and will soon run out of money. Of course this is clearly not the case. The projections that are derived from the Social Security Trustees’ intermediate assumptions show that the program could pay all scheduled benefits for the next 27 years even if nothing is done. After 2037, the projections show that Social Security would still be able pay a benefit that is larger in real terms than what current retirees receive, even though it would be just 75 percent of the scheduled benefit. The payable benefit would continue to rise through time, so that even if nothing is ever done to change the program, a retiree in 2100 could anticipate a benefit that is more than twice as high as what current retirees receive today.

Presumably Congress will not allow the payable benefit to fall below the scheduled benefit. If a shortfall really was imminent, it is likely that Congress would make the necessary adjustments to keep the program paying full benefits. This is exactly what happened in 1982-83, when the program literally did run out of money. Congress took steps to ensure that benefits were paid each month. It then established the Greenspan Commission whose reforms laid the basis for another 54 years of solvency. Adjustments of the size put in place in 1983 could keep Social Security fully solvent into the 22nd century even if we waited until 2030 to act.

These are the basic facts about the state of the program, yet only a small share of the public knows them. This matters hugely in terms of the willingness to accept cuts in the Social Security. People are far more likely to accept cuts in the program if they never expected to see their benefits anyhow. On the other hand, if there were widespread awareness of the fact that the program was fully funded for the near-term future and largely funded for the indefinite future then there would likely be more objections to proposals that substantially reduce benefits.

The public’s ignorance of Social Security only matters if there is reason to believe that it will be better informed in the future. This is the case, primarily because of recent trends in the media.

Traditional news outlets are mostly owned and controlled by individuals who are deeply hostile to Social Security. The best example of such an outlet is the Washington Post, which regularly uses both its opinion and news pages to promote the view that the program is in crisis, that benefits are far too generous, and that large cuts are essential. As a result of having one of the largest circulations in the country and also being located in Washington, the Post is enormously influential in public debate.

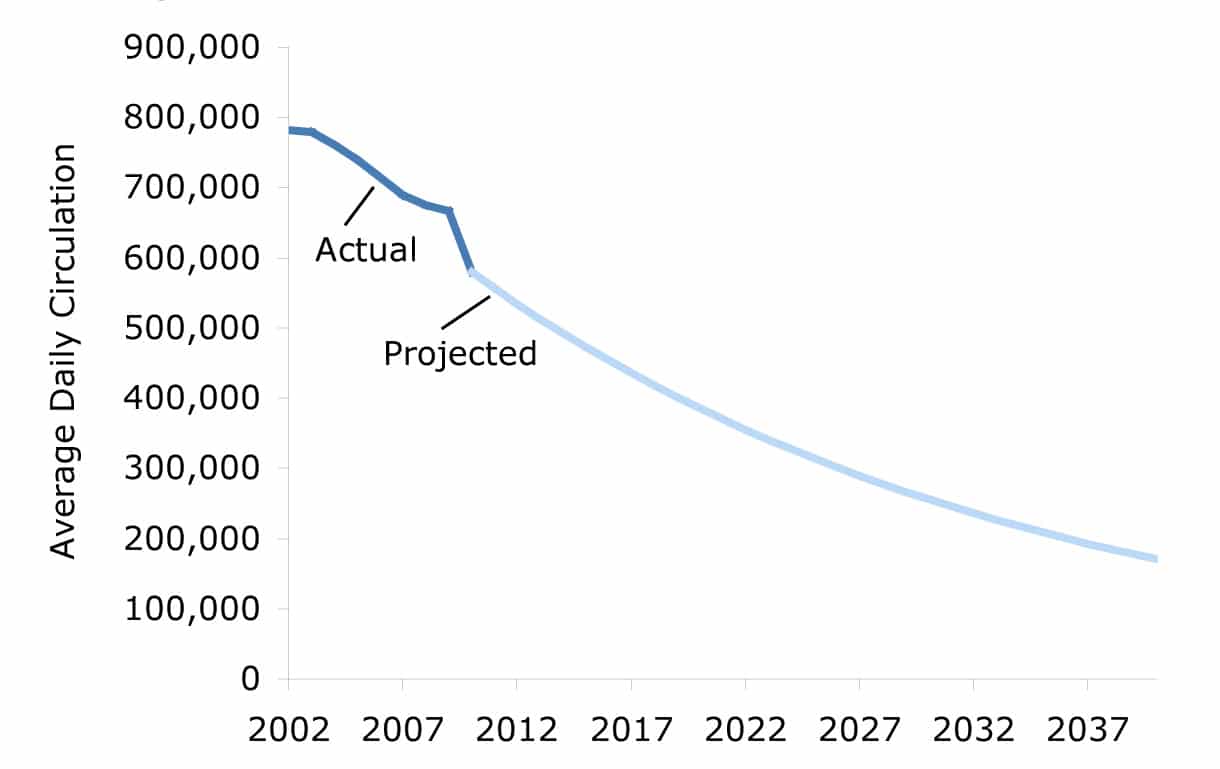

However, the Post‘s circulation is falling rapidly. Figure 1 shows data on the Washington Post‘s average daily circulation from 2002 through 2010 and projects it forward until 2040. Daily circulation has already fallen from close to 800,000 in 2002 to less than 600,000 in 2010. If the Post‘s circulation continues its 3.7 percent annual rate of decline, then it will be under 400,000 by 2020 and less than 300,000 by 2030. It can be assumed that the paper’s influence in national debates will experience a corresponding decline.

FIGURE 1: Washington Post Circulation

Source: ABC Reader Profile Studies and ABC Audience-FAX eTrends

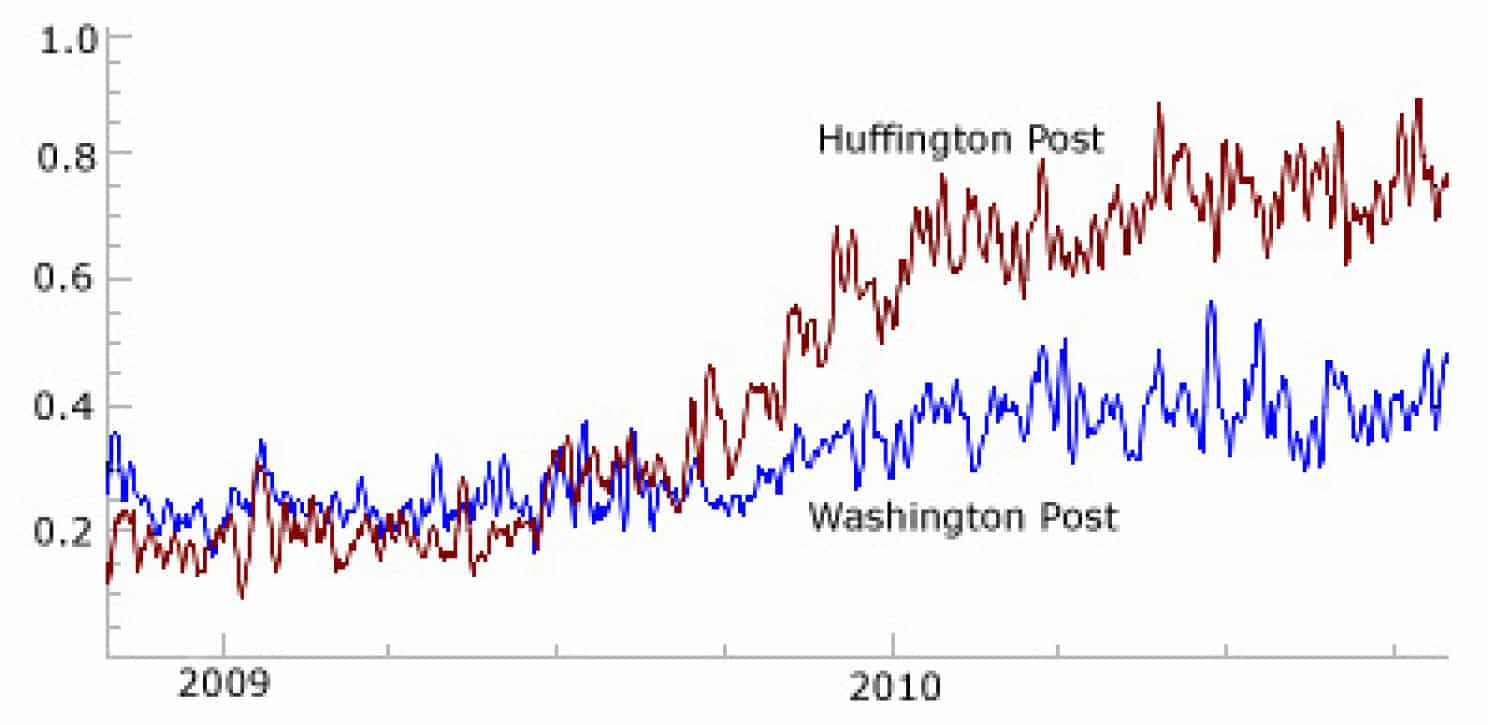

By contrast, many of the new media outlets that are growing have a more informed and nuanced view of the program. For example, the Huffington Post, one of the largest of the exclusively web-based news sources, has many reporters and columnists who take a more balanced view of Social Security’s finances.2 While circulation at the Washington Post has been shrinking, the number of web viewers of the Huffington Post has been growing rapidly. The number of viewers of the Huffington Post first began to regularly exceed the viewers of the Washington Post in the second half of 2009. By the second half of 2010 the Huffington Post was drawing almost twice as many viewers as the Washington Post, as shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2: Washington Post and Huffington Post, Global Reach (% of all Internet Users)

Source: Alexa.com

These two news outlets are representative of a larger trend of new media sources supplanting the traditional media outlets. While not all new media outlets can be expected to give the same treatment to Social Security as the Huffington Post, and not all traditional news outlets are as hostile as the Washington Post, it is likely that the mix of rising new media outlets will be substantially more balanced in their treatment than the declining old media outlets. For this reason, it is likely that the public will be much more knowledgeable about the true state of Social Security in 10 or 20 years than it is today.

The Growing Dependency on Social Security

The baby boom generation is now reaching the age of eligibility for Social Security. As a result, the number of people who are receiving benefits is projected to rise rapidly over the next two decades. The strongest supporters of Social Security are the people who are dependent on the program. This is not only out of self-interest. Beneficiaries appreciate the program more than the rest of the population. They know how important it is for sustaining their standard of living and they also know that Social Security is there for them, as opposed to the tens of millions of younger people who think that the program is about to evaporate.

Seniors consistently oppose cuts not just to their own benefits, but also to benefits for their children and grandchildren. They want future generations to be able to benefit from the program just as they have. For this reason, the greater the share of the population that is actually dependent on Social Security, the harder it will be for politicians to implement large cuts.

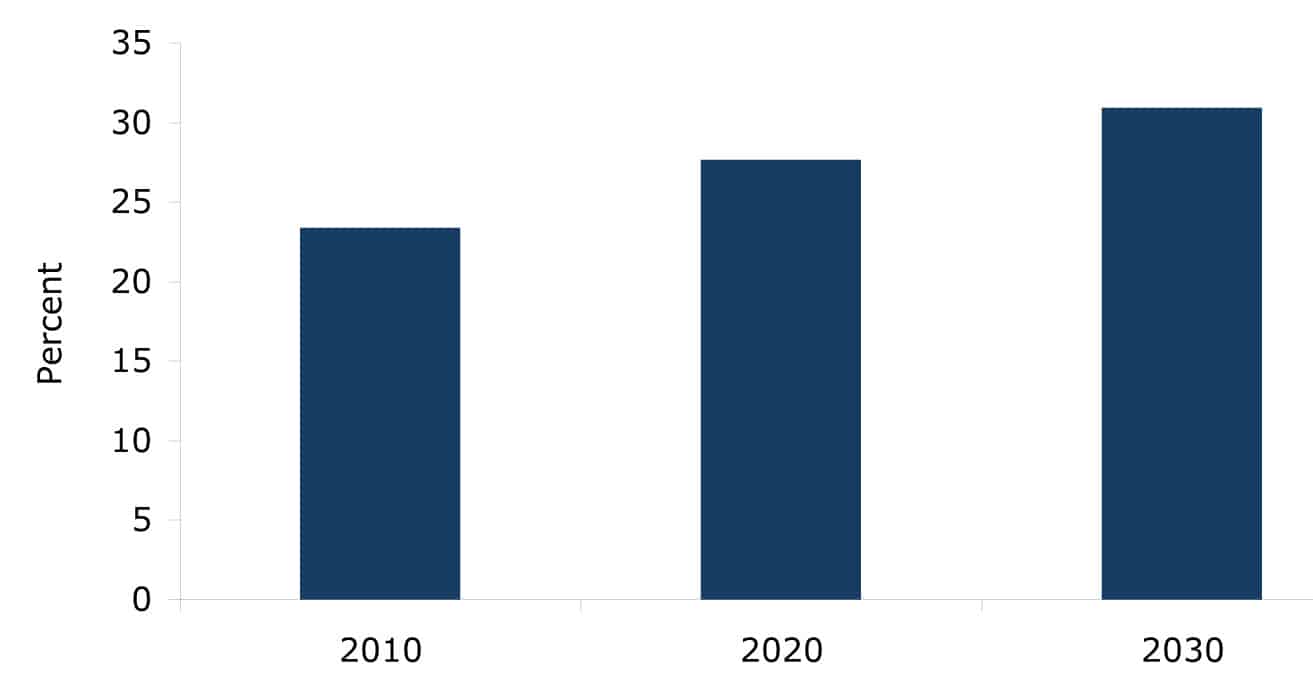

Figure 3 shows the percentage of the adult population that is projected to be dependent on Social Security. The percentage of beneficiaries rises from 23.5 percent in 2010, to 27.8 percent in 2020, and to 31.0 percent in 2030. By 2030, the share of the voting age population that will actually be receiving benefits from Social Security will be nearly one-third higher than it is today. Given the age skewing among actual voters (the elderly turn out in higher percentages), the growth in the share of beneficiaries among voters may be even larger. This will mean that it will be far more difficult for politicians to support benefit cuts in 2020 or 2030 than in 2010.

FIGURE 3: Ratio of Social Security Beneficiaries to Adult Population

Source: 2010 Social Security Trustees Report, Tables V.A2, V.C4, and V.C5.

Protecting the Victims of the Housing Crash from Another Attack

One of the main arguments of proponents of early action on Social Security is that eliminating the shortfall will be easier if we move quickly. This usually means that if we make the current generation of near retirees receive lower benefits, then the future tax increases and/or benefit cuts that will be required to balance the program’s funding will be less. While this is logically true, it raises the question of whether it is desirable to make near retirees accept lower benefits.

The current cohort of near retirees (people between the ages of 50 and 65 in 2010) has been the victim of a uniquely bad period in American economic history. Most of the members of this age cohort saw little by way of wage gains during their working lifetime as a hugely disproportionate share of the benefits of productivity growth went to those at the top of the income scale.

In addition, the limited wealth that they were able to accumulate during their working years was largely destroyed by the collapse of the housing bubble. As a result, the vast majority of these workers are approaching retirement with little other than their Social Security to support them. The median net worth (including home equity) of older baby boomers (between the ages of 55 and 64) is just $170,000.3 This would leave the median household with roughly enough money to pay off the mortgage on the median house and then be entirely dependent on Social Security for all their expenses. The median late baby boomer has roughly $80,000 in net worth including their home equity, roughly enough to pay off half the mortgage on the median house.

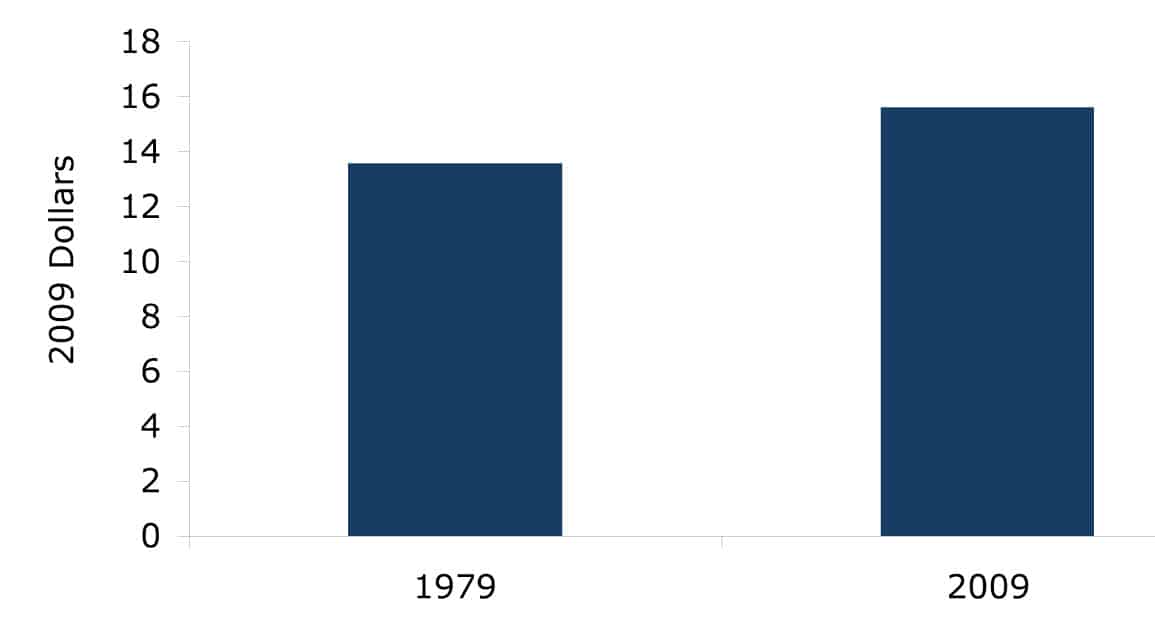

Figure 4 shows the median real hourly wage for 1979 and 2009. As can be seen, the median hourly wage rose by just 14.6 percent over this 30-year period even though productivity grew by more than 50 percent. By contrast, median wages rose more or less in step with the rapid productivity growth that the U.S. economy experienced over the years 1947 to 1973. By 1973, the median real wage was almost twice as high as it was at the end of World War II

FIGURE 4: Median Real Hourly Wage

Source: Author’s analysis of Current Population Survey data.

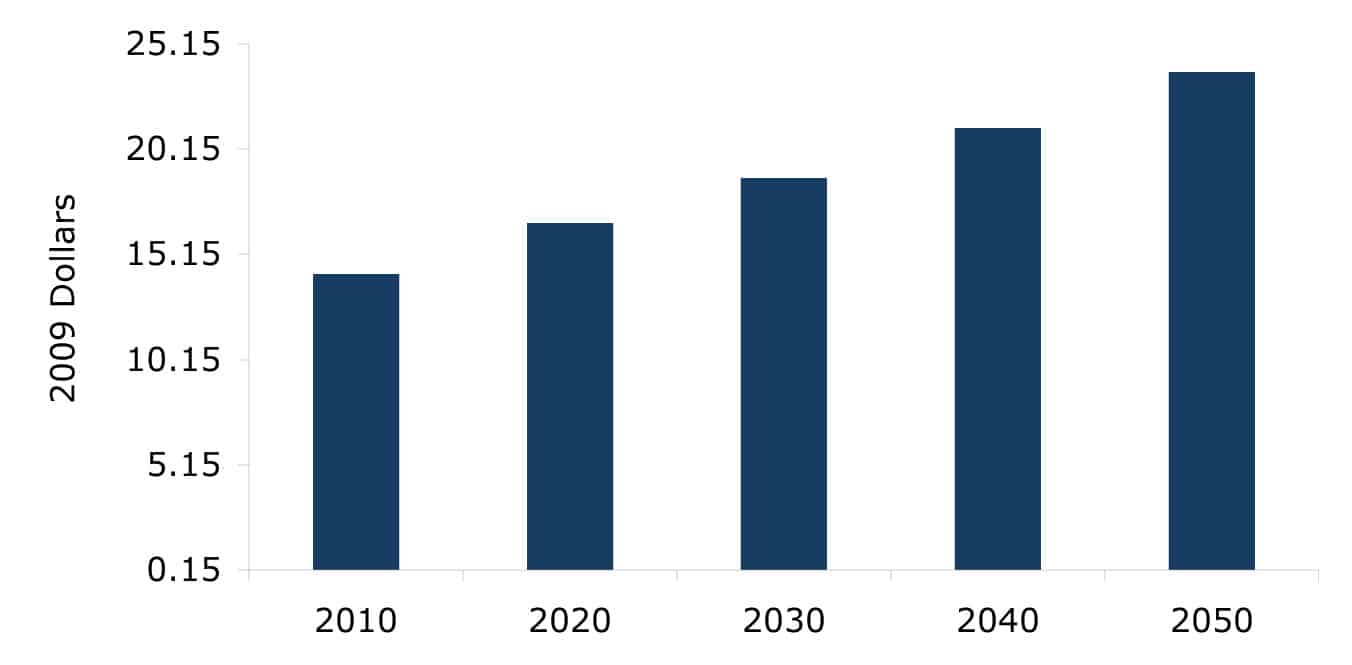

The Social Security trustees projections assume that there will be little increase in inequality in future years. If this is the case, then median wages will rise pretty much in step with average wages. Figures 5 show projections for the real median hourly wage over the next four decades under this assumption.

FIGURE 5: Projected Median Real Hourly Wage

Source: Social Security Trustees Report, 2010, Table V.B1 and author’s calculations.

In this scenario, median wages will be more than 25 percent higher in 2030 than they are today and more than 60 percent higher in 2050. There is no guarantee that the Trustees’ projections will prove accurate on either wage growth or distribution, but if they are, then they imply that young workers just entering the labor force will see substantial improvements in living standards over their working lifetime. Such gains will far outpace the gains of their parents’ or grandparents’ generations. This would suggest that an approach to Social Security that was concerned with generational equity would more likely turn to these younger generations for tax increases and/or benefit cuts rather than imposing a further burden on the cohort than has been the primary victim of the economic policy and mismanagement of the last three decades.4

The Con Game: Reassuring Financial Markets

One of the arguments often given for cutting Social Security benefits is that — even though we know the economy can easily bear the additional costs that Social Security will impose in coming decade — it is necessary to make cuts to the program to reassure financial markets. This is perhaps the most cynical rationale of all.

The reality is that no one knows exactly what will reassure financial markets. Furthermore, reassurance is not a yes/no proposition. The relevant question would be exactly how much reassurance would be bought with cuts of what magnitude? No one has attempted to answer this question, probably because it would expose the absurdity of the whole effort.

Guessing what financial markets will do in response to various policies and/or events is a difficult task. There are a small number of people who do this well and are highly rewarded. None of the people who make the argument that we need to cut Social Security to reassure financial markets are prominent members of this group of knowledgeable market forecasters. (Taking a saying from a different context, this appears to be a case where those who tell don’t know, and those who know don’t tell.)

It is a common political tactic to claim that a policy that cannot be supported on other grounds must be pursued to appease financial markets.5 Even if there may be a short-term movement in financial markets that follows a particular policy change, it does not follow that this movement will be lasting. In other words, it could be the case that the stock market will jump by 10 percent if large cuts to Social Security are put in place. However, this could just be the result of the fact that market actors are expecting the market to rise in response to the cuts. The movement may not reflect their actual assessment of the economy or future corporate profits and therefore may not be enduring.

Furthermore, it is not clear that the movement in the market would even be desirable from the standpoint of the economy as a whole. Suppose that a cut to Social Security benefits led to the further inflation of a stock bubble. This would have the effect of leading to a stock-wealth-induced rise in consumption and decline in national saving. This would be undesirable from the perspective of everyone except the small group of people who hold large amounts of stock. If a bubble-inflating rise in stock prices is the predicted effect of a cut in Social Security benefits, then it would be a strong argument against cutting benefits, not an argument for cuts.

As a practical matter, anyone wishing to argue that cuts to Social Security are necessary to assuage financial markets should be expected to lay out specifically what they expect the impact of a particular set of cuts to be on markets. That way, both the validity of the claim and the expected benefits of the outcome can be assessed. In the absence of such specifics, arguments for cuts to Social Security based on their impact on financial markets do not deserve to be taken seriously.

Conclusion: Social Security Can Wait and So Should We

There is no good reason for rushing forward with changes to Social Security. The official projections show that the program will be fully solvent for nearly three decades with no changes whatsoever. The necessary changes that are projected to be needed to keep the program fully solvent in subsequent decades are not especially large compared to budgetary changes made in prior decades, such as the military build-up in the 80s or cost of the wars in the last decade.

Given the extraordinary degree of misinformation surrounding the program, the country would be well advised to wait until the public is better informed before making major policy changes. Recent trends in the media suggest that this is likely. Similarly, the growing percentage of the population that receives Social Security will also increase knowledge of and appreciation for the program. It is understandable that the proponents of large cuts and/or privatization would like to rush action in order to take advantage of the public’s ignorance, but it is difficult to see why the program’s supporters would go along.

1 For example, a CNN poll conducted in the summer of 2010 found that 60 percent of adults under the age of 60 did not believe that Social Security would be able to provide them with any benefit when they retired. Seventy percent of those under the age of 50 did not believe that Social Security would be able to provide them a benefit when they retire. (Results viewed at Pollingreport.com on 11-2-10, “Social Security,” at www.pollingreport.com/social.htm.)

2 The author’s columns occasionally appear in the Huffington Post.

3 These estimates are taken from Rosnick, David and Dean Baker. 2009. “The Wealth of the Baby Boom Cohorts After the Collapse of the Housing Bubble.” Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research. Available at www.cepr.net/documents/publications/baby-boomer-wealth-2009-02.pdf.

4 See Schmitt, John. 2009. “Inequality as Policy: The United States Since 1979.” Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research. Available at www.cepr.net/documents/publications/inequality-policy-2009-10.pdf.

5 In the fall of 2008, when the TARP was originally voted down by the House of Representatives, proponents of the program seized on the plunge in the stock market that day as evidence of the need for approval of the program. None of these TARP advocates took the much steeper plunge in the market that followed the approval of the TARP as a signal that the program was a failure.

Dean Baker is an economist and Co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, in Washington, D.C. This article was first published by CEPR in November 2010 under a Creative Commons license.

| Print