The establishment survey showed the economy adding just 39,000 jobs in November. As a result of slow job growth, the unemployment rate rose to 9.8 percent. The employment-to-population ratio (EPOP) fell to 58.2 percent, the low hit in December of last year. The EPOP for white men and white women both dropped below their prior troughs. The EPOP for men fell to 67.3 percent, just below the 67.4 percent level of last December. The EPOP for white women fell to 55.2 percent, 0.1 percentage points below the 55.3 percent level of October. The EPOP for Hispanics also hit a new low of 58.5 percent, while their unemployment rate hit a new high of 13.2 percent.

By age, workers over 55 appear to be doing best, having an employment gain of 123,000, while employment for younger workers fell 73,000. This continues a pattern that has been present since the beginning of the downturn. Employment for workers over age 55 has risen by 1,783,000 since the start of the recession. It has fallen by 1,389,000 for workers between the ages of 25-34 and by 1,819,000 for workers between the ages of 45-54. However, the biggest job loss has been among workers between the ages of 35-44, who have seen a drop in employment of 3,540,000, or 10.4 percent.

There were no clear patterns in job loss by education level. The EPOPs for workers without college degrees fell in November. However, workers with college degrees had the biggest rise in unemployment rates, with a 0.4 percentage point jump, pushing the unemployment rate for college grads to 5.1 percent, a record high.

Other data in the household survey were consistent with a very weak labor market; although there was a decline of 217,000 in the number of people involuntarily working part-time. The number of discouraged workers jumped to 1,282,000, almost 50 percent above its year-ago level.

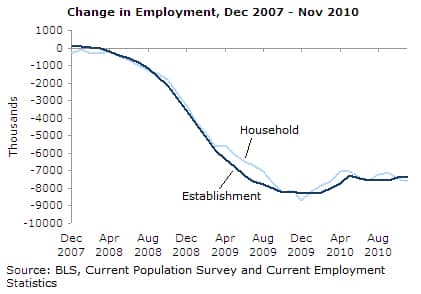

Interestingly, the household survey has shown a drop in employment of 17,000 since March, a period in which the establishment survey shows a gain of 690,000 jobs.

The data in the establishment survey offer little hope of the labor market improving anytime soon. The 50,000 job gain in the private sector was the weakest performance since a 16,000 increase in January. Any evidence of building momentum appears to have dissipated. Both construction and manufacturing lost jobs in November, 5,000 and 13,000, respectively. Employment is likely to stabilize or even rise slightly in manufacturing in the months ahead, but falling non-residential construction will lead to further job loss in that sector.

Retail trade lost 28,100 jobs in November, with a decline of 14,500 jobs in general merchandise stores leading the way. This is consistent with a view that stores began their Christmas seasons early, beginning their hiring in October instead of November. This should also dampen the optimism around the relatively good November sales figures released this week.

Health care added 19,200 workers in November, while restaurants added 11,700, both almost equal to their average over the last year. Employment services saw modest growth in November, adding 44,800 jobs and bringing the three-month gain in the sector to 120,000 jobs. While this is a positive sign, it is still weak growth for a recovery. Last year, employment services added 107,000 jobs in the month of November alone. State and local governments shed 13,000 jobs in November. This will continue to be a drag on an already weak economy.

One positive sign is that hourly wage growth has increased at a 2.2 percent annual rate over the last quarter. This suggests that wages are at least keeping pace with inflation.

There is very little basis for optimism about the near-term future in this report. There is no sector showing strong job growth at this point. Furthermore, average weekly hours actually fell slightly for non-supervisory workers, suggesting that the demand for labor might actually be weakening. With house prices again dropping rapidly and additional cutbacks coming at all levels of government, there are no obvious engines of growth in this economy.

Dean Baker is an economist and Co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, in Washington, D.C. This article was first published by CEPR on 3 December 2010 under a Creative Commons license.

| Print