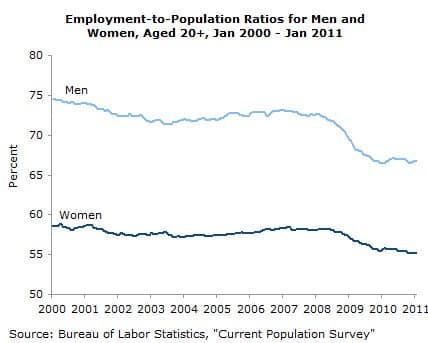

For the second consecutive month, the unemployment rate fell by 0.4 percentage points, despite the weak job growth reported in the establishment survey. The establishment survey showed a gain of just 36,000 jobs in January, following a revised gain of 121,000 jobs in December. The big gainers in January were white men, who saw their unemployment rate fall by 0.6 percentage points for the second consecutive month; although at 7.9 percent it is still somewhat higher than the 7.0 percent rate for white women, which is a decrease of 0.3 percentage points since December. The unemployment rate for Hispanics also fell by 0.6 percentage points to 11.9 percent. The latest data from the employment-to-population ratio for men is still 7.7 percentage points below its peak in 2000, while the EPOP for women is down by 3.6 percentage points. There was little change in the employment situation of blacks. Their overall unemployment rate of 15.7 percent remains near the peak for the downturn, as does the 45.4 percent unemployment rate for black teens.

By educational attainment, the biggest gainers were college graduates who saw a 0.6 percentage-point drop in their unemployment rate to 4.2 percent. The unemployment rate for college grads has fallen from 5.1 percent to 4.2 percent in two months, a decline of 17.6 percent. The unemployment rate for people without high school degrees fell by 1.1 percent in January, but this was associated with a 0.3 percentage point drop in their EPOP.

There were also 524,000 people involuntarily working part-time. This figure is down by 1.1 million from its September level.

Month-to-month comparisons are made difficult by the change in the population controls in the household survey. With the change in controls, employment rose by 117,000; however, the gain would have been 589,000 had it not been for the change. While this is a large difference with the 36,000 job gain shown in the establishment data, such discrepancies are not uncommon, especially in the month of January.

In January of 1992, 1994, and 1997, the household survey showed gains in employment (not counting any population control effects) of 512,000, 502,000, and 438,000, respectively. These gains exceeded the gains reported in the establishment survey by 463,000, 234,000, and 235,000, respectively. In January of 2000, the employment gain (adjusted for the change in controls) was 784,000, or 535,000 more than the gain shown by the establishment survey.

The numbers in the surveys tend to converge over time. The household survey had been showing slower employment growth than the establishment survey. The increase in employment since January 2010, adjusted for the change in controls, is 1,284,000. This compares to a gain of 984,000 jobs in the establishment survey.

The picture in the establishment survey is mostly quite bleak. The average rate of job creation over the last three months has been just 87,000, a rate that is not fast enough to keep pace with the growth of the labor force. Furthermore, there is no sector showing especially strong growth.

Retail added 27,500 jobs, but this followed two months where it had lost 12,800. Healthcare added just 10,600 jobs, less than half its average over the last year. Restaurants reduced employment by 4,400 in January. State and local government reduced employment by 12,000, and construction employment fell by another 32,000. Finance lost 10,000 jobs. There was an anomalous loss of 44,8000 courier jobs, but this reversed a jump of roughly the same size in December. The one notable bright spot was manufacturing, which added 49,000 jobs, which seem to be centered on the auto industry.

There is little evidence that employers are about to pick up the pace of hiring. Jobs in the temp sector increased by just 13,200 after rising at an average rate of 31,500 in the prior three months. Average weekly hours actually fell slightly from 34.3 to 34.2 hours. And wage growth remains very weak with the average hour wage increasing at just 1.54 percent annual rate over the last quarter, down from a 1.96 percent rate over the last year.

Dean Baker is an economist and Co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, in Washington, D.C. This article was first published by CEPR on 4 February 2011 under a Creative Commons license.

| Print