There is much confusion about the current economic situation, among left media and organizations as well as in the mainstream media. This is certainly understandable given its complexity. But what many are referring to as causes are symptoms of a deeper underlying problem — in other words, sparks that produced the Great Recession by igniting the fuel that was already present. In order to decide what to do about the current dismal situation, it is essential to have an understanding of the underlying problem.

The symptoms that many confuse with the cause run the gamut — from lending for “sub-prime” mortgages to government deregulation of the financial industry to the chicanery and outright fraud that existed in the financial sector to the increasing levels of inequality of wealth and income. Now many see the “problem” in state and local government debts and the national debt. Others come up with “explanations” that are further afield — somehow it’s all connected to “peak oil.” There have even been claims of not enough savings and lack of capital. Incredibly, the assertion of insufficient capital is made at a time when there are still trillions of dollars of capital literally sloshing through the global financial system as the wealthy look for profitable ways to invest their funds.

How Bad Is the Current Economic Situation?

Well, it all depends upon who you are and where your interests lie. Actually things are going pretty well if your name is John Paulson and you manage a hedge fund, you received $5 billion in profits in 2010 (enough to pay 100,000 people a wage of $50,000 each for the year), and, because of a tax loophole, your income will be taxed at the low capital gains rate rather than as ordinary income. Or things are pretty good if you are managers or hold stock in some of the major corporations — US business has accumulated around $2 trillion in profits, money it really doesn’t know how to profitably invest. And there are lots of other people not doing badly even in these times. However, if you are a regular “working-stiff” or one of the unemployed, things are not going well at all. There are currently some 15 million people officially considered unemployed. But if you add in those who have become too discouraged to look for work (and aren’t considered “officially” unemployed) and those who need full-time work but can only find part-time work, there are some 25 million people who need jobs. To put this in some perspective, the private sector currently employs less than 110 million people. And with state and local governments shedding jobs for the foreseeable future and Congress in a ridiculous and highly hypocritical tizzy regarding the Federal debt, the private sector is all that’s left to produce jobs. But how in the world is the private sector going to increase employment by some 23 percent within any reasonable period of time? When taking into account the natural growth of the working age population, this means continually adding around 250,000 total net new jobs a month for close to 10 years. Such a continuous addition of so many jobs for so many years never happened before, and the chances of it happening over the next decade are close to zero.

There are other issues aside from just the number of unemployed. About forty percent of the unemployed have not worked for more than 27 weeks. In addition, there are 1.4 million “99ers” who have reached the end of the extension of their unemployment benefits, and their numbers are expected to increase significantly during 2011. The psychological and physical effects on the unemployed — especially the long-term unemployed — are devastating. Even during times when jobs are increasing, there is a lot of “normal” turnover, with over 20 million people fired each year. And though many of these get new jobs quickly when the economy is growing quickly, losing a job has a negative effect on a person’s self-esteem and long-term health prospects.

Underlying It All

The issues mentioned above as possible causes of the Great Recession and its aftermath are but symptoms of a critical underlying fact of life of capitalism: the growth of the economy (that is the Gross National Product or GDP — the sum of goods and services produced during the year) has been stalling for a long time.

Lets take a look at what has happened over the last 80 years (Table 1). There can be little doubt that the U.S. economy has been slowing down ever since the so-called “golden years” of the 1950s and 1960s that followed the Second World War. But why has the slowdown occurred, and why to such an extent that the economic growth in the most recent decade is more similar to the 1930s than any decade since?

Table 1: Real Average Annual Growth of GDP by Decade

| Average rate of growth (% per year) |

||

| 1930s | 1.3 | |

| 1940s | 5.9 | |

| 1950s | 4.1 | |

| 1960s | 4.4 | |

| 1970s | 3.3 | |

| 1980s | 3.1 | |

| 1990s | 3.1 | |

| 2000s | 1.9* | |

* Note: for 2001-2010 the average is 1.8 percent growth.

Source: calculated from Real Gross Domestic Product, St. Louis Federal Reserve “FRED” database,

research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/data/GDPCA.txt

The explanation given by economists such as Paul Baran, Paul Sweezy, and Harry Magdoff is that stagnation is the normal situation of “mature” capitalist countries. With the basic societal infrastructure — highways, electric transmission lines, water supplies for cities, etc. — already built and monopoly and oligopoly conditions developing, the search for profits leads to a capacity to produce becoming far greater than the ability to sell everything that could be produced. During an upswing in the economy capitalists invest in more capacity based on assumptions of continuing growth and desiring to gain market share. The overcapacity this creates leads to a constant and more frantic search to find ways to sell more — leading to a vast increase in the sales effort. This problem also creates a push to try to sell goods abroad, something that many governments, including the Obama administration, view as one of the ways to help the economy get out of the current situation. But even before the Great Recession began, there was a huge overcapacity in many sectors — in the U.S. and the world. For example, there was the capacity to produce about 30 percent more automobiles in the US and the world than were being purchased. (For much of the 2000s before the Great Recession began, the automaker GM was losing money on the cars they produced but was able to keep going because its financial division, GMAC, was so profitable.) Investment in the productive sector (the “real” economy) tends to slow down in response to large amounts of excess capacity. After all, what’s the point of investing in new plant and equipment and retail stores when there is already overcapacity? With investments in the real economy of goods and services declining, this not only affects the present but puts future growth and job creation at risk. A few mature economies — Germany is a prime example — are able to grow their economy by exporting more than they import. Obviously, simple math and logic indicates that not all countries can do this.

So what needs explaining are not the periods of stagnation, but, rather, the periods of rapid growth. A number of economists have pointed to the extraordinary transformative effects of certain technologies — in other words, technologies that caused such changes and had so many spinoffs that there was significant self-propelling growth for prolonged periods. The railroads in the late 19th century was one of those transformative technologies — affecting society and the economy dramatically and in such ways that led to a prolonged period of economic expansion. Free land was given to the builders of the transcontinental railroads, new towns sprung up along the lines, and others grew in response to the increased economic activity that rails provided. Agricultural products could be more easily shipped to markets, making farming the Midwestern region more attractive. Railroads encouraged European settlers to populate vast stretches of the country. In a period of forty years (1850 to 1890) the United States rail system grew from 9,000 miles to over 160,000 miles. More steel was needed not just for the rails but for the rail cars, the storage bins for grains near rail terminals, etc. By the early 20th century the railroads directly employed over 1 million workers — some ten percent of the industrial workforce. This was a technology that had so many spinoffs and stimulated so many other aspects of life and the economy that its effects lasted for years.

A more recent transformative technology was the “automobilization” of the U.S. — the mass use and multitude of direct and indirect effects of the automobile was explosive in the post-Second World War era. The auto industry used a lot of labor as did the supplying industries. But there was also the huge undertaking of the interstate highway system which is still having effects today decades after it was finished, as it stimulated the growth of suburbs, the development of the trucking industry as the main way to ship goods within the country, the zillions of fast food outlets, gas stations, repair shops, motels and hotels, large box store centers growing near interstate exits, etc. In the immediate post-Second World War years there was also a large stimulus provided by the pent-up demand (and savings) during the war, the sales of goods for rebuilding Europe and Japan, the Korean War, etc. Nevertheless, all the offshoots of the automobile undeniably provided for a long wave of self-propelling growth, as capitalists made investments to build new factories, stores, homes, etc., which in themselves stimulated employment, and then provided more jobs as the new facilities and equipment were put to use to make new things and services for sale.

There has been no transformative technology introduced since then — transformative in the way the railroad and automobile produced self-reinforcing growth, directly and through the multitude of spinoff effects. What about the computer and all the electronic gadgets we now have? Many, of course, are produced abroad and do not directly produce many manufacturing jobs in the U.S. Some of the new information technology (IT) has clearly allowed companies to “do more with less,” a nice way to say that they can fire people and have the remaining workers do more by working more efficiently. Introduction of labor-saving technology is nothing new — it’s been going on ever since the beginning of the industrial revolution. So while the “computerization” of the U.S. has certainly affected how we live, work, and communicate, transport goods and keep track of inventories, and so on, it has not transformed the economy into a prolonged period self-propelling growth.

How Did Capitalists and Government Respond to Stagnation?

As we might expect, when the economy grows at increasing slower rates, capitalists find fewer ways to profitably invest their money in the “real” economy of goods and services — where commodities are actually produced and sold. So how in the world are they going to use their money to make more money? The accumulation of capital is the very purpose at the root of the capitalist system. Thus in the 1980s capital turned to an old technique — increasing orienting their activities to make money by using only money, producing no product or service at all. “Something for nothing. It never loses its charm,” as Michael Lewis has put it. Thus capitalists began to grow the financial system (that made making money with money possible) and used their influence in government to clear the barriers to making money in this fashion, while making sure that new barriers weren’t imposed.

But How Do You Make Money without Making a Tangible Product or Service?

Let’s take a look at how it’s done. These are some of the main ways:

a) Loaning money to, for example;

- individuals wanting to buy or improve homes (mortgages), or to buy cars (auto loans), or to buy a variety of consumer items (credit cards);

- corporations wanting to expand (including buying up competitors); and

- private capital that wants to buy companies only to legally loot them (by taking on new company debt and using the money to pay “fees” to themselves) and then resell the companies — buy it, strip it, and flip it, as the saying goes.

b) creating an unending variety of bets (called “financial instruments” or “financial products”) and then sell them to speculators (“investors”) who think that they might make some real money on these bets. Some of these are backed by an asset or a promise to pay (such as pools of mortgages); some are backed by nothing — just betting on things as simple as whether the price of corn or gold or natural gas might go up or down and as complicated as a computer-derived formula that no one really understood. There are literally trillions of dollars a day that are bet on the change in prices of currencies vs. one another. If you want to, you can bet that a particular company or even country will not be able to pay off its bonds. It was, and continues to be, literally a giant casino — you can bet on literally anything imaginable and lots of things that are quite unimaginable to normal human beings. The gambling created even more debt as the big players used high amounts of leverage, placing their bets with 20 or 30 dollars or more of borrowed money for every dollar of their own.

As the “financialization” of the economy progressed, an increasing share of corporate profits were derived from this sector that made nothing — just before the beginning of the Great Recession (in 2007), 40 percent of all domestic corporate products came from financial sector. Finance, which had been an important, but small, part of the economy (doing such things as providing loans to companies in the “real economy” or helping them raise the money from others), became a dominant sector with vast political influence at the highest levels of the national government. During this time all sorts of chicanery occurred — as the 19th century French writer Honoré de Balzac said, “Behind every fortune lies a great crime.” Financial institutions peddled stuff that they knew was junk. And the firms that were supposed to grade “investments” as to their quality or safety were, in the words of a hedge fund manager, “turning all this garbage into gold.”

One of the ways to make money in the mortgage (and house-building industry) was to sell “subprime” mortgages — that is, sell mortgages to people who could not afford to pay for the houses they were buying. Michael Lewis, the author of numerous books on the financial system explained that a hedge fund manager he was interviewing knew that “subprime lenders could be scumbags. What he underestimated was the total unabashed complicity of the upper class of American capitalism.” These “subprimes,” given mainly to people with lower incomes, contained many extra fees which made these much more expensive for borrowers. The ultimate subprime loan was a “ninja,” granted with “No verification of Income, Job status, or Assets.” Now comes the good part — the companies that sold the mortgages and got fees from borrowers then turned around and packaged the mortgages along with many others and carved them up into pieces and sold the pieces to “investors.” Since the mortgage originators didn’t keep the mortgages and service them, they wanted to shovel as many of these out the door as possible. There are many complexities that I’ve glossed over, but the essence was explained by an article in the Washington Post (Dec. 16, 2008): “The Wall Street machine cranked out CDOs [the packages of mortgages known as Collateralized Debt Obligations] full tilt from 2005 to 2007. It was a race against time as accelerating delinquencies ate away at the value of mortgage-backed securities that served as collateral for many of the deals. No one was trying to contain the erosion; rather, the players had every incentive to get the securities that backed the deals out of their inventories, so they created as many CDOs as possible.”

What’s the Underlying Cause and What Are the Symptoms?

One of the first signs that a financial crisis had arrived was the losses in value of these CDOs as people couldn’t pay their mortgages. The whole crisis has been referred to as “the subprime mortgage crisis.” Were the subprime mortgages or other financial gimmicks, chicanery, and fraud really the cause the crisis? It makes more sense to view these as natural outcomes of an increasingly “financialized” economy and the economic and political power of the financial interests that grew side-by-side with their wealth. And, to work backwards, the whole increase in the money going into the financial system was a result of having few other places to make lots of money. Sure there were opportunities here and there to invest in the real economy. Huge retail outlets were built and small niche industries created and other such activity took place. But these could not absorb the literally trillions of dollars of capital that was looking for, and “needed,” places to make money.

As with the subprime mortgages, the deregulation of the financial industry was not the problem or even one of the problems. Of course, deregulation of the financial system allowed worse things to occur than they otherwise would have. But deregulation is but a symptom of the political power of the financial sector.

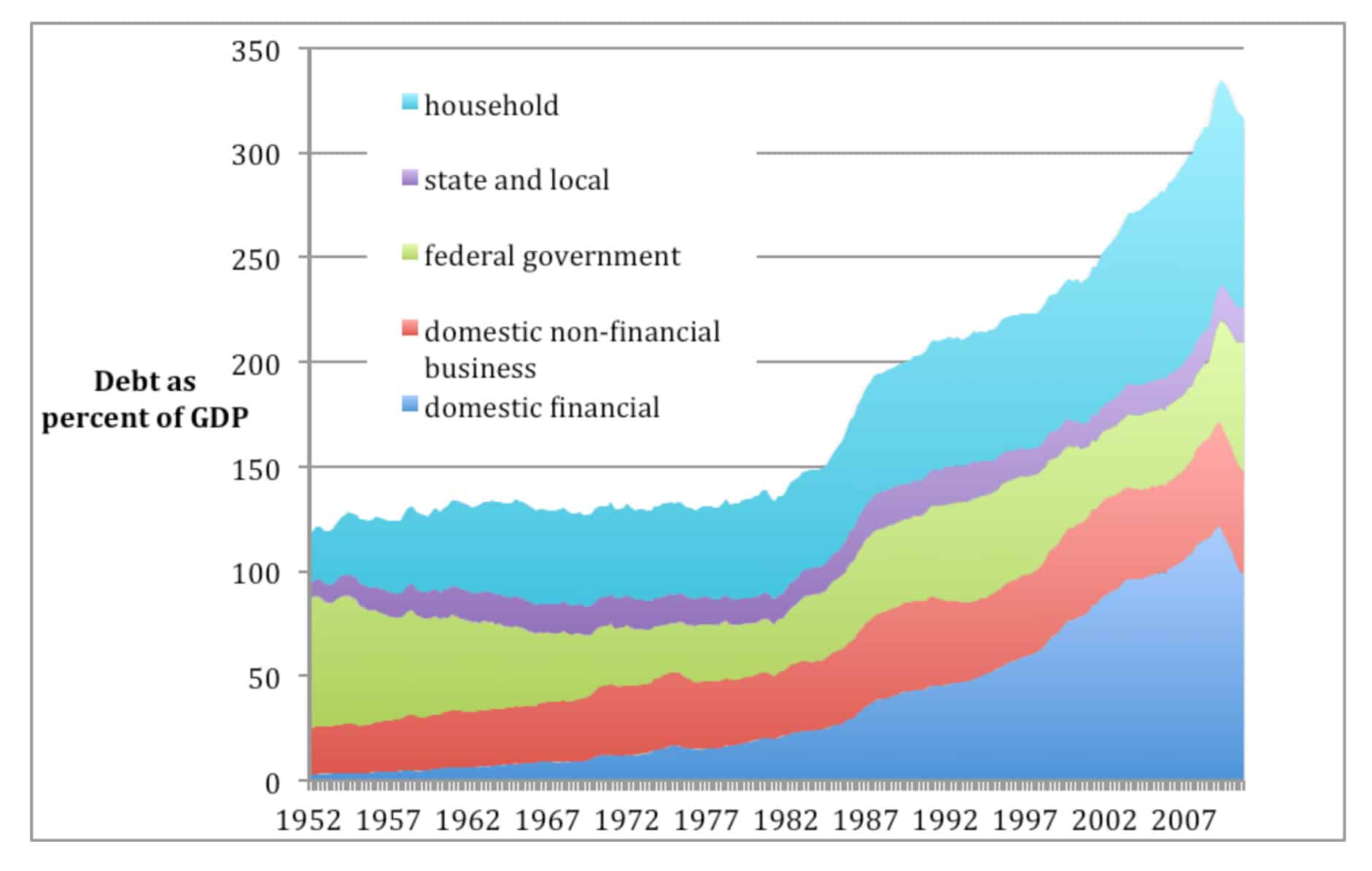

The spectacular growth of the financial sector along with its resulting political power allowed the legal and illegal “irregularities” to occur. And another symptom that developed as the financial system grew — and has not received the attention it deserves — is the nearly incomprehensible growth in debt in all levels of society. It’s not just that debt increased, it increased greatly relative to the underlying economy. This includes household debt, business debt (financial and non-financial businesses), and debts of the local, state, and national governments (chart 1). Total system-wide debt reached a high level of 330% in 2007 and has decreased only slightly in the aftermath of the Great Recession.

Chart 1: Debt of Economic Sectors as percent of the GDP, 1952-2010

This huge and increasing debt from the 1980s to 2007 made the system more and more fragile. The economy depended on increased levels of debt — so people could maintain their standards of living in the face of stagnating wages, so that people wouldn’t complain about the cost of wars because they were financed by debt (so their children and grandchildren could pay for them), so that companies could buy out other companies, so that private capital could buy a company and take out a lot of debt to pay itself back and then sell the company on the stock market, and so on. Increasing debt — relative to the underlying real economy — was critical to keeping it all going. Without increasing levels of debt, the bubbles that kept developing — the housing bubble only being the latest — would not have been possible. Although there is no absolute limit to amount of debt that a society can bear relative to its economy, the higher the debt the less the possibility of extending it further and the more fragile the system becomes. When the economy is so fragile and loaded with debt, any upset can make it hard for people, companies, and governments to pay back what they owe. For instance, the decreased tax income due to the Great Recession, added to the decision not to fully fund the pensions for their employees, has put many state and local governments in a very precarious position — not wanting to increase taxes (or not being able to do so for political reasons) and not having the income to pay all their bills.

Another issue that’s mentioned as causing the crisis is the growing inequality of both income and wealth, back to levels not seen since just before the Depression of the 1930s. With a lower share of the country’s annual income going to the mass of people, people are able to purchase less of the output — especially when they have maxed out their borrowing ability. This very high degree of economic inequality is a real concern from moral and political, as well economic, viewpoints. But the return to outrageous inequality only demonstrates the power of the wealthy to appropriate more of the nation’s wealth. And where did this power come from? Out of the increasing dominance of financial interests and the ability of financial and non-financial wealth to convince media, legislators, and presidents that deregulation was good, that unions had too much power, and that the tax “burden” on the wealthy was holding back the economy by causing them to invest less. (This last argument is, of course, ridiculous — the real problem was not a lack of capital. There were, and are, hoards of capital looking for places to make money. The problem was the opposite of too little capital — there was too much money searching for ways to make more money.)

But again, we have in the growth of debt and the increase in inequality two more symptoms. Growing debt is the natural outcome of an economy that is becoming increasingly dominated by the financial interests. In fact, that is one of the main ways they make money — by loaning it out or borrowing it themselves from other companies in order to leverage their gambling bets. The increase in inequality in the sharing of the country’s wealth is also an indication of the growing strength of financial interests (as well as the weakness of labor’s position relative to capital). And, the financialization itself was the response of the system — capital and government, hand-in-hand — to the tendency toward stagnation.

So no matter where we look, whichever symptom we explore, it all leads back to the tendency of the economy to stagnation and how business and government respond to the stagnation.

So Let’s Sum Up the Argument

The simplified diagram below outlines some of the consequences of stagnation, to help us distinguish between cause and effect (Chart 2). Once the economy is very fragile, a number of different sparks may be able to set the stage for a severe recession. These appear as causes, but are instead only the visible results of processes largely hidden from the view. And they all derive from the reality of a stagnating economy and the ways that business interests and governments have tried to continue creating opportunities to make profits in such an environment.

Chart 2: Simplified Diagram of Consequences of Stagnation

If the Underlying Problem Is Stagnation, Then What’s to Be Done?

The discussion above should have made it clear that the U.S. economy is, to say the least, in a very difficult situation. Chickens, which for decades have been kept away by the growth of debt, gimmicks, and bubbles, are apparently coming home to roost for a while. What makes the situation so potentially intractable and long-lasting is partially the depth of the crisis — there’s a big hole to dig out of because of the temporary measures taken each time a previous crisis arose did not solve the underlying problem. These actions delayed a severe crisis but also made the economy even more fragile. More importantly, the visible symptoms of crisis are the result of a basic characteristic of the system — the tendency toward stagnation — that has been obscured from the public and most economists.

It is not at all clear where the jobs are going to come from to absorb all those millions of people currently needing work as well as the growing numbers of working-age people. There is no truly epoch-making transformative technology on the horizon that can generate the number of jobs needed — not the computer, not “green energy.” It is always possible that one will come along, but I would not suggest betting a lot of money on seeing such a development in the near future. Given the pathetic ability of the private sector to create anywhere near the needed number of jobs, it seems that only a massive Depression Era WPA-type of jobs program will be able to put the huge numbers of people needing jobs back to work.

But there is also another alternative — building a different economic system. One based on satisfying the needs of people in place of the system we have which is based upon accumulation of profits without end. Although this may well seem utopian and far removed from the realities of everyday life in the United States today, an economic system that has as its very foundation to serve the people and protect the environment is the only way to assure a) jobs for everyone, b) the basic necessities of life for everyone, and c) the possibility of reversing the catastrophic degradation of the environment caused primarily by a system that must grow to avoid economic crisis and knows no natural boundaries.

Fred Magdoff (fmagdoff at uvm.edu) is professor emeritus of plant and soil science at the University of Vermont and adjunct professor of crop and soil science at Cornell University. His most recent book is Agriculture and Food in Crisis (co-edited with Brian Tokar, Monthly Review Press, 2010).

var idcomments_acct = ‘c90a61ed51fd7b64001f1361a7a71191’;

var idcomments_post_id;

var idcomments_post_url;