The unemployment rate edged up again in May, reaching 9.1 percent, as the rate of private-sector job growth slowed to just 83,000. There were also downward revisions to the prior two months data, which lowered the average for the last three months to 160,000, approximately 70,000 more than what is needed to keep pace with the growth of the labor force. Some of the weakness in May probably stemmed from quirks that exaggerated April job growth. For example, the retail sector reportedly added 64,000 jobs in April. It lost 8,500 in May. Health added 36,700 jobs in April, compared with an increase of just 17,400 in May. Food manufacturing added 6,300 jobs in April, it lost 7,000 in May. These are most likely quirks of seasonal adjustments, not sharp shifts in the economy itself.

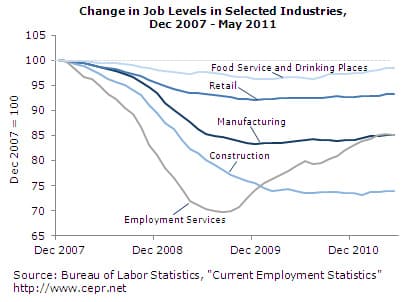

Taking a longer, three-month snapshot, there is not much that is very encouraging. A loss of 5,000 jobs in manufacturing brings the average gain over the last three months to 13,000. Construction added 2,000 jobs in May, bringing its average gain to 4,000. Job growth in retail has averaged 16,700 over the last three months. Health care has added an average of 28,000 jobs since February. The rate in restaurants has been 23,000.

Construction employment is likely to remain close to flat for the rest of the year. Manufacturing may go back to adding jobs, but probably only at a rate of around 10,000 per month. At that pace, it will take two decades for employment to return to its pre-recession level.

One especially discouraging sign was the loss of 2,200 jobs in the employment services sector following a weak gain in April. The weak growth in this sector, coupled with the stagnation in hours, suggests that job growth is not likely to accelerate soon. The weakness in the private sector goes along with a government sector that lost 29,000 jobs in May and has lost an average of 24,300 jobs over the last three months.

Wage growth remains weak. Over the last three months the average hourly wage increased at a 1.6 percent annual rate. This is down slightly from its 1.8 percent rate of growth over the last year.

There was nothing in the household data to suggest a brighter picture. The overall employment-to-population ratio (EPOP) was unchanged at 58.4 percent, just 0.2 percentage points above its low for the downturn. The EPOP for African Americans fell by 0.3 percentage points to 51.2 percent, hitting another new low for the downturn. The EPOP for black men fell 0.8 percentage points to 56.1 percent, a new low. The EPOP for black women was unchanged at its low for the downturn of 53.7 percent.

By education, the least educated are faring worse, with the EPOP for workers without high school degrees falling 0.4 percentage points to 38.5 percent, also a low for the downturn. Interestingly the data on unemployment by industry shows a sharp year-over-year drop for construction. The 16.3 percent May rate is 3.8 percentage points below the May 2010 level. The current rate suggests that unemployment in the construction industry may at most be adding 0.3 percentage points of structural unemployment.

Unemployment spells are again getting longer with both the mean and median durations rising. The mean duration rose to 39.7 weeks, a new high for the downturn.

There is very little positive news in this report. It should be viewed in conjunction with the stronger growth in April, which makes the picture somewhat better. However, even the 160,000 average growth over the last three months was very weak for this stage in a recovery, and there are more signs suggesting slower growth than any acceleration.

The decline in house prices seems sure to continue for the rest of the year. This loss of wealth ($1 trillion since last summer) coupled with wage growth that is lagging inflation will ensure weak consumption growth. State and local governments will continue to make cutbacks, and there is a strong likelihood of further cuts in federal spending in the fiscal year beginning October 1. The unemployment rate may continue to creep upward without new stimulus.

Dean Baker is co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington, D.C. He is the author of several books, including False Profits: Recovering from the Bubble Economy. This article was first published by CEPR on 3 June 2011 under a Creative Commons license.

| Print