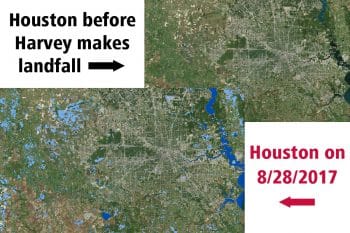

Top-right: TerraSAR-X satellite image before the hurricane. Bottom-left: TerraSAR-X recordings of 29 August 2017 showing high-water areas (light-blue) and water courses (dark blue). Credit: DLR (CC-BY 3.0).

As Harvey continues to wreak havoc in the Southeast, one issue is starting to emerge as a growing threat to public health and safety: Houston’s vast oil, gas, and chemical production landscape. We’ve already seen accidental releases of chemicals at facilities owned by ExxonMobil, Chevron, and others. Now we are seeing explosions at Arkema’s Crosby facility 20 miles northeast of Houston, due to power failures and flooding. And there remains a threat of additional explosions.

There is no reason to believe the Crosby facility is the only one at risk of chemical disasters right now. The coast of southeast Texas and Louisiana has a whole lot of petrochemical production—infrastructure that was exactly in the path of Hurricane Harvey and continues to be hit by its remnants. I’ve studied (and been worried about) chemical safety, sea level rise, and storm surge risk to oil and gas infrastructure in the Gulf for several years, and many of those fears are now playing out. Here are some things we know about petrochemical production in the Gulf, its storm risks, who’s impacted, and who’s responsible.

1. Arkema’s Crosby Plant explosion risk shows the danger of President Trump’s chemical disaster policy.

Back in June the Trump administration delayed the EPA Risk Management Plan rule until February 2019. Finalized in January 2017, the new EPA RMP rule is designed to enhance chemical risk disclosure from companies, improve access to risk information for emergency responders and the public, and push companies to consider safer alternatives and preventative measures. Yet, the rule is now delayed more than a year, thus delaying the time when companies will be preparing for and disclosing details about their chemical risks and safety measures.

Today’s explosions at Arkema are exactly the reason that chemical safety policies are so important. We are witnessing in real time the confusion that results from limited access to chemical safety information in an emergency situation. As the situation at the Crosby facility (Tier 2 under the RMP) continues to unfold, the media, decisionmakers, law enforcement, and the public are scrambling to figure out what chemicals are on site and what public safety risks remain for nearby communities and first responders. The facility’s current risk disclosure is limited in detail. This shows that the improved RMP rule is sorely needed. The rule’s needless delay is putting public safety at risk.

2. Oil refineries are routinely damaged in major storms, climate change makes that worse.

You know how people tell you to buy gas when there’s a storm in the gulf? The advice isn’t unfounded. A significant portion of U.S. oil refining capacity is in the Gulf of Mexico, and refining operations are shut down days in advance of storms. At least 22% of U.S. refining capacity is offline right now thanks to Harvey. Such shutdowns disrupt major supply chains and affect gas prices across the country, for weeks or months after. Refineries are especially vulnerable to storm impacts, with 120 oil and gas facilities within ten feet of the high tide line. Oil and other chemical spillage is now expected during major storms. When Superstorm Sandy struck in 2012, for example, Phillips 66’s Bayway refinery in Linden, NJ, spilled 7,800 gallons of oil.

Under a changing climate, this vulnerability worsens for a few reasons. The Gulf Coast faces rates of sea level rise that are among the highest in the world, partly because segments of land in the region are subsiding. This means storms ride in on higher seas, able to worsen storm surge levels. Further, thanks to warmer sea surface temperatures, climate change is expected to increase Atlantic hurricane intensity, meaning the storms that do form could be more damaging, with higher winds and greater rainfall totals. Yet, we’ve seen the Trump administration repeatedly roll back, walk back and revoke policies in place to help us mitigate and manage these types of risks.

3. Refinery spills and leaks harm surrounding communities.

After Murphy Oil’s Meraux refinery spilled 25,000 barrels of oil during Hurricane Katrina, more than a square mile of neighborhood was contaminated and Murphy Oil had to pay $330 million in settlements. Photo: UCS/Jean Sideris.

What makes the above points more concerning is the fact that people live close by. Like really close. Thanks to a lack of zoning laws and environmental racism, people in Houston live at an eyebrow-raising proximity to oil and gas infrastructure.

Take the Manchester Community, for example, sandwiched between the major roadways, a rail yard, and oil and gas infrastructure. A report from the Union of Concerned Scientists and Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services (T.e.j.a.s) last year found that low-income communities and communities of color face disproportionate impacts in Houston when it comes to chemical safety risk and exposure to harmful industrial emissions. The report found large disparities between Houston communities in terms of overall toxicity levels from chemical exposures, showing that toxicity levels from exposures in Manchester are more than three times higher than in more affluent and white Houston communities.

Low-income communities and communities of color are routinely exposed to adverse impacts from refinery emissions, and in storms they are also likely to bear the brunt of the impacts, with less money and attention spent on their recovery. We need to make sure that communities most impacted by this tragedy get a fair share of the recovery efforts. If you’d like to donate in a way that supports these communities, a list of organizations is here. And if you’d like to support T.e.j.a.s. and the Manchester community, you can do so here.

On top of this, we know that chemical spills are likely to be a more lasting and problematic element to the recovery than the water alone. Cleaning toxic chemicals out of houses is no easy or cheap task. After Katrina, for example, damaged tanks at Murphy Oil’s Meraux refinery spilled 25,000 barrels of oil, covering over a square mile of neighborhood and contaminating 1,700 homes. Murphy Oil paid $330 million to settle 6,200 claims, buy contaminated property, and perform cleanups. One graffiti sign in a nearby neighborhood read “Damaged by Katrina, Ruined by Murphy Oil, USA.”

4. Refineries are regulated, but that hasn’t been enough.

Where there are refineries, there’s exposure to toxic chemicals. Refineries are of course subject to regulations designed to protect people from harmful levels of pollution; however, disasters like Harvey show the inadequacy of those regulations. Refineries often have spikes in emissions that can expose nearby communities to unsafe levels of pollution. This happens on a normal day. During a storm event with flooding or wind impacts, these chemical releases are more likely. First, many refineries shut down in advance of approaching storms. This sounds positive, and emissions will stop, right? In fact, this can mean (and has, in the case of Harvey) a lot of flaring that releases chemicals into the air.

On top of this, the state has temporarily shut down its air monitoring, leaving it to companies to self-report to nearby communities, a situation that likely means communities have limited access to air quality information. Ramping up refineries after a shutdown also comes with risks of explosions and unsafe emissions. The Chemical Safety Board, which monitors and advises industry on chemical safety issues, has urged companies to exercise caution and follow protocol closely when starting up refining operations after the storm, given the higher accident risks during startup. The Chemical Safety Board, by the way, was on the chopping block in the President’s recent budget. Without it, an investigation into what happened at Arkema’s Crosby plant and how to prevent it in the future will never happen.

5. Companies should be held responsible for any spills that happened.

Public companies are required to report and prepare for any material risks their businesses face, including extreme weather and climate change. Companies don’t always do a good job of disclosing this information, however. As a result, the public doesn’t know much about what risks companies have and what they are doing to mitigate those risks.

Indeed, investors, communities, and public interest groups have long been demanding that companies do a better job of disclosing such risks. In 2015, a group of investors and the Union of Concerned Scientists asked Exxon Mobil, Chevron, Marathon Petroleum, Phillips 66, and Valero to improve their disclosure of climate and storm risks. Some responded, but since then we’ve only seen modest improvements in company disclosure of such risks at their refineries.

In Exxon Mobil’s 2016 risk disclosures, for example, the company wrote that its facilities are “designed, constructed, and operated to withstand a variety of extreme climatic and other conditions, with safety factors built in to cover a number of engineering uncertainties, including those associated with wave, wind, and current intensity, marine ice flow patterns, permafrost stability, storm surge magnitude, temperature extremes, extreme rain fall events, and earthquakes.” Yet we learn few other details about what conditions they are thinking about and what preparations are in place to mitigate those risks. The irony, of course, is that these companies are dealing with the consequences of climate change, as they are continuing to contribute to it through emissions of their products.

6. None of this is new.

In many ways, Harvey is unprecedented. Its levels of rain boggle the minds of even the most imaginative meteorologists. But we had all the information we needed to prepare for this event. The hurricane was forecast far in advance. We knew that climate change stands to make such events worse. We knew how to prepare communities and infrastructure for major storms. We knew why we shouldn’t build infrastructure in floodplains and why we shouldn’t design infrastructure that can’t withstand wind and water risks.

Yet, we live in a world where our president revokes policies that ensure our infrastructure is storm ready, where climate mitigation efforts have stagnated, and where disaster relief efforts often don’t reach those that need it most.

We must do better. We must remember the tragedy that is unfolding before us right now and use it to advance policies that ensure that future events like this are less likely and less damaging when they do happen. Our nation’s future depends on it.