The Great Refusal: Herbert Marcuse and Contemporary Social Movements. Edited by Andrew T. Lamas, Todd Wolfson and Peter N. Funke, with a Foreword by Angela Y. Davis. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2017. 405pp, $44.95, pbk.

We are, the 1960s radical generation, now once more marching, marching, sometimes it seems mostly with the Millennials by our side. And here comes the ghost of Herbert Marcuse, who was so much with us the first time around.

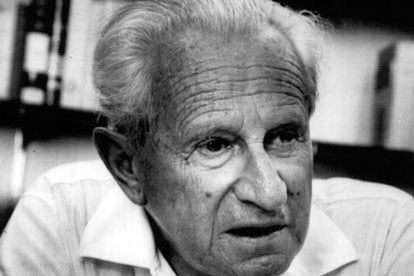

It is a truism that Marcuse has been going in and out of style (at any rate, public attention) since well before his death in 1979. Indeed, he only came into style, as a widely recognized, beloved and despised, figure during the later 1960s, with the rise of the global New Left. Conservatives and grumpy liberals—clearly displaced in attention by someone to their Left and worse, someone who supported young people’s movements—viewed the refugee intellectual entering late middle age as a veritable public menace. “Ma-Ma-Ma,” that is, “Marx-Mao-Marcuse,” a conglomerate monster, Marcuse himself became a third of the mocking phrase meant to ridicule young people’s idols as babyish, immature, the youngsters themselves incapable of recognizing really important intellectuals and the obligation to protect American credibility amidst the War in Vietnam.

That was, of course, a while ago. And the notoriety of the day disguised most of the longer story of the erstwhile Frankfurt School savant who specialized in philosophy—and wrote the distinguished intellectual history Reason and Revolution—but became famous for his elucidation of Freud, Eros and Civilization. When Marcuse became doubly charismatic for a sort of popularization of his own ideas, One Dimensional Man, graduate students (like this reviewer) went digging through his earlier works. Student orators, rousing the collegiate rabble against the Draft and the War, were said to pore through One Dimensional Man the night before the Big Speech, along with another contemporary professor’s book, The Tragedy of American Diplomacy. “They send us to war but they don’t want us to screw.” It was a message, at the reductionist level, with a convincing punch line, even as in loco parentis continued to fade away and young couples rejected their parents’ dire warnings against pre-marital sex. “The more I rebel, the more I want to make love,” in the French phrase of 1968.

Several anthologies of essays about Marcuse, along with a host of Marcuse reprint volumes notably recovering his essays in German and offering his classics with fresh commentary, have appeared over the decades. This one, The Great Refusal, is a sparkler, undoubtedly the best of the critical anthologies. Drawn from a symposium organized at the time of Occupy, it speaks to us vividly today, with mass movements erupting against the new Trump administration. It is at once more global than previous scholarly anthologies about Marcuse, it goes further in evaluating Marcuse alongside other theorists, and it is the first to go far in relating Marcuse’s work to the Black Liberation Struggle.

Angela Davis offers the keynote, “Freedom is a constant struggle.” Marcuse, as “the philosopher of refusal and liberation,” proudly and defiantly “stood with his students, demonstrating the power of youth to transform the world.” She was herself one of those youth and Marcuse was…her teacher. Davis ends her note by urging his appeal for the “Great Refusal” be re-examined, understood and used by the newer generations. It’s a heavy thought for any group of essays to live up to.

And yet these do, in a large volume with a doubtful or overly dense entry or two. Among the strongest would be two essays co-authored by Andrew Lamas (himself also a former student of Marcuse). The first if these, “Mic Check!” treats the Occupation, and the second, “The Great Refusal in a Dimensional Society,” stands are an Afterword to the volume. The lesson here and elsewhere is: ideas count

Joan Braune’s “Hope and Catastrophe Messianism in Erich Fromm and Herbert Marcuse” is actually an anti-Marcuse essay, the odd recollection of social-democratic Fromm who blasted Marcuse’s embrace of young radicals. Braune evidently misses or underrates the depth of the rivalry factor here: Fromm, vastly more famous than his fellow exile in 1960, became vastly less famous over the next decade and beyond. She also does not grasp the ambience of the political moment in the creation of a peace movement. Very quickly, after 1965, the movement divided between those who saw the exit from Vietnam as the only possible end of the war, and those who most urgently did not want the US to “lose” Vietnam, roll history’s dominoes in the wrong way, and give those dastardly communistic nationalists in Vietnam a Win. The latter urged a continued US presence, or as we jokingly described their position, “A little less bombing, please!” It may help to know that the Socialist Party/Social Democratic Federation, in which Fromm played a large symbolic role, was in the process of splitting between a faction that demanded Victory (thus, militantly opposing George McGovern) and a faction that tardily reformed as the DSOC, the Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee. For all his good intentions, Fromm was out of his depth and unable to join we “OUT NOW!” activists.

A few other essays seem to stretch the main conceptual points of Marcuse’s contributions, in order to make the legacy relevant today. I am not so sure of “Asia’s Unknown Uprisings” by Marcuse student George Katsiaficas, although the essay offers some valuable insights into those uprisings. Likewise the essay following, “Chinese Workers in Global Production and Local Resistance,” by Jenny Chan. Marcuse’s biographer and scholar for his previously unpublished essays, Douglas Kellner, perhaps comes the closest to threading the needle with “Insurrection 2011: Great Refusals from the Arab Uprisings through Occupy Everywhere.” If Marcuse has not supernaturally returned to our time, there’s no doubt Kellner has articulated the philosopher’s keen responses for this ghost.

I am especially interested in the essay by Peter Marcuse, the emeritus Columbia professor who has evoked his father’s visions, most notably in Missing Marx, about the former East Germany, after the fall of the East Bloc. (I have a special interest: I happened to have been there for a week in 1990,when other options still seemed open.) “Occupying and Refusing Radically: The Deprived and Dissatisfied Transforming the World” offers a sweeping picture of his father’s response to the reality that the Proletarian Revolution is nowhere in sight. What could “revolution” mean under these circumstances? “All forces of opposition today are working at preparation and only at preparation,” with the uncertainty of the situation pointing either leftward or rightward. How much more relevant than this is now, after the election of 2016, need not be underlined. Nor Peter Marcuse’s conclusion that the “liberation of consciousness” will be necessary in any strategy of the urgently needed transformation.