By the end of the XIX century, it was impossible to imagine an authentic social Revolution that did not base its dreams of redemption in the figure of the human being, a beacon that overgrows the limits of race and nation, was already unimaginable. The Greek democracy excluded slaves and women and the ideologues of the bourgeois revolution would ignore the colonized peoples. But neither could them, nor farmers and workers of the metropolis, emancipate themselves without a humanist conception that embraced all of them, even colonists or operators. When Napoleón Bonaparte accepted, before the belligerence of the insurgent, the abolition of slavery only in the colony of Saint Domingue, Toussaint Louverture, an illiterate black person who had been a slave protested:

What we want is not a circumstantial freedom conceded just to us —he said with a “realist” political wit, alien to any pragmatic posture—what we want is the absolute adoption of the principle that states that any man, born red, black or white, can’t be the property of their neighbour. Today we are free, because we are the strongest. The Consul maintains slavery in Martinica and in the Bourbon island; so we will be slaves when he is stronger.

In 1871 José Martí, with barely 18 years, denounced the blindness of the heirs of the Enlightenment who in Spain defended the rights their were denying in their colonies:

(…) even the men that dream of a universal federation, with free atoms inside the free molecule, with respect towards foreign independence as the base of force and their own independence, cursed the petition of rights that they asked for, sanctioned the oppression of independence they preached, and sanctified as representatives of peace and moral, the war of extermination and the oblivion of the heart. (…) They asked yesterday, they ask today, the broadest freedom for them, but yet, they applaud the unconditional war that suffocates the freedom petition of everybody else.

Marti himself, leaves in 1895 a basic concept for the Cuban revolutionaries: “The motherland is humanity, is that portion of humanity that we see closer to us and in where we happen to be born”. The Cuban independence guaranteed the physical and moral space for a Republic of Justice and Solidarity, with the poor people of the Planet, even though Martí, as well as Bolivar, dreamt of a bigger Motherland, that would integrate all the people that live from the Bravo river to the Patagonia.

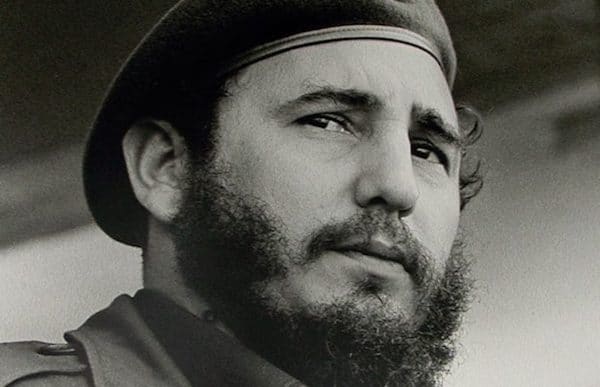

No other Latin American Marxist was such a preacher of Marti’s ideas than Fidel Castro. Marti and Fidel were the only leaders in the brief and intense Cuban history, that achieved the necessary unity of the revolutionary forces; a unity alien to conciliator pacts, capable of disassembling the domination consensuses -which stated the incapacity of the Cuban, the inferiority of the woman and black man, the inevitability of dependence-, and founding the ones of emancipation, with virtuous men and women who overcame themselves. Fidel, like Martí, had faith in the victory, in his people, in the reasons of struggle, in the possibility of what seemed impossible. He picked up both colonial and neocolonial emancipatory traditions -with Marti as one of the main outstanding figures-, the traditions of the exploited in the Capital, of Marxist thought and of the October Revolution, whose 100th anniversary was recently celebrated.

The Cuban Revolution of 1959 thought itself as part of the rebellion of the colonized and exploited people of the world, as a step in the difficult fight towards emancipation of the human beings. It is true that revolutions are not exported, that they are born from unrepeatable and specific conditions, but the concept of solidarity, based in justice, is basic in socialism, and it can’t be a good that corresponds to limits like a house, neighborhood or country.

Fidel’s Cuba exercised solidarity among brothers, without any conditions nor geopolitical calculations, and it didn’t stop before the conveniences that contravened their principles; they did so in Asia, Africa and Latin America. Cubans donated blood in massive amounts for the assaulted Vietnamese, we yielded a pound of our sugar fee to the Chile of Allende, we struggled alongside those who fought for their people in other lands of the world, and there were many who perished on the way; we advanced, hand in hand along with Sandinistas and triumphant Bolivarians, in the edification of the new country. We built schools, hospitals, saved or fixed hundreds thousands of beings who lacked of medical attention. Internationalism was an unbreakable principle that was exercised with a clear sense of the historical moment.

Fidel’s Cuba didn’t stop before ideological considerations or shameful regimes that conspired to overthrow it, and it sent doctors to Somoza’s Nicaragua when the earthquake of 1972 devastated country’s capital. It built a contingent that has carries the name of an internationalist New Yorker of our first independence war, in order to help the American people after hurricane Katrina. The only ideology that they wielded wasn’t articulated in words: it was centered around the actions, the unselfishness, the dedication. Two hundred fifty six Cuban health workers attended to the people that suffered the worst outbreak of Ebola in Western Africa and in the whole World. There, they found African doctors of the affected countries and from other countries of the continent that studied in Cuba, some even in High School and Pre-University School, like many other Arab and Latin American youths.

When in 1998, Hurricane Mitch razed the Central American Caribbean -another hurricane of ideological character had paralyzed the international left, after the downfall of the so called “socialist field”- Fidel re launched internationalism and with him, the certainty that another better world is possible if there is political will. Each medical brigade that traveled to a country in a disaster situation or that had applied for our help, was personally dismissed by him, who insisted in the idea of respecting the traditions, beliefs and political credos of the patients they would attend.

Fidel, would actually reactivate the work of solidarity of every authentic revolution after a dark and luminous decade of resistance, the 90s -the foundational solidarity, backed up by a crisis of conduction that always avoided to harm the most poor people and which survived, despite deficiencies and shutdowns, in the so called “bottle” of the streets of the city- and expand it towards the exterior, with the Integral Health Plan in Central America and Haiti (after that Venezuela would be incorporated), and towards the interior, with the Battle of Ideas, which sought to rescue young people from least favored demographic segments. Both actions of solidarity had always an impact in the interior of the country: each health worker that saved lives in precarious conditions, in marginal or intricate zones and every social workers that would guide their peers down the beautiful and cobbled path of self improvement, could (if they had it inside) “recycle” their own revolutionary spirit.

Making justice central was the only way to reactivate the Revolution.

In this context, Fidel found an equal: Hugo Chávez. Together they covered every wasteland, every river, every mountain, every urban neighborhood of Our America, every heart of a Latin American. Together their shouted: Let it be unity in solidarity!

The concept of Fidel’s Revolution (the ethical code), acquires sense in the context of Fidel’s life and work. If Motherland is Humanity, Socialism is justice and it is revolutionary Humanism. None of the aspects or ideas that this concept shows can be understood if they are unframed from the main principle: the struggle against injustice, wherever it happens, and against capitalism and imperialism, is what is needed. Who says that Fidel doesn’t live anymore? His concept of Revolution exceeds the words that compose it; and it interacts with history, past history and future history; because without justice there is no Motherland, without solidarity -internal and external-, there is no Motherland, without the conquests we achieved, and the ones we want to achieve, there is no Motherland.