The FCC is under attack—and so too is the First Amendment. As the primary regulator of how media and information gets to our nation’s citizens, the Federal Communications Commission has a critical role to play in protecting the open Internet, free speech, and free press in our democracy. Though the agency has always enjoyed a cozy relationship with the industries it regulates, ever since the Trump administration arrived in Washington, the FCC’s mission to preserve the public commons has been threatened, assaulted and torn asunder. And like a bad horror movie cliché, these calls to eviscerate the FCC have been coming from inside the agency.

Repealing net neutrality has drawn a huge amount of public visibility—and rightly so—but that decision is just the latest in a string of ominous, industry-friendly giveaways by the Trump administration’s FCC. It has also rolled back local TV station ownership limits on media giants like Sinclair Broadcasting Group and rescinded the longtime “main studio” rule that required local stations to maintain community newsrooms and fostered more local journalism. And the agency’s leadership has begun a campaign to actively abdicate its enforcement mission and pass it over to the smaller, less well-funded Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which lacks the FCC’s deep industry knowledge and proactive regulatory power.

“This is the worst FCC I can remember,” says Michael Copps, bluntly. Copps, who served as FCC commissioner from 2001 to 2011 and now advises Common Cause’s Media and Democracy Reform Initiative, says he has watched new FCC chair Ajit Pai’s leadership with growing alarm. “There’s an audacity to it, a lack of process. It’s just God-awful,” Copps says of the agency’s breakneck pursuit of a reactionary, “market-based” agenda. “This FCC is on an outright tear to wreak untold damage on our media ecosystem, on our news and information, free speech, democracy and self-government.”

Death of the Open Internet?

The FCC’s 3–2 vote to repeal net neutrality—with the two Democratic commissioners dissenting—is the most high-profile and controversial step the agency has taken in the Trump era. It reverses a rule passed by the Obama administration FCC in February 2015 that put internet traffic under the “Common Carrier” protections of Title II of the Communications Act of 1934. In effect, net neutrality means the government prohibits cable companies and Internet Service Providers (ISPs) from blocking, slowing or otherwise discriminating against the web traffic of their users. Much like a public utility, all content to the consumer must be treated the same—hence, net neutrality. Right-wing opponents of the rule—which included then-Commissioner Pai, who voted against net neutrality—complained it was a case of unnecessary government overreach, and made a series of apocalyptic claims about its potential impact.

“One of the things that’s really outlandish about how this FCC has gone about its net neutrality proceeding is that Pai has just straight-up ignored all the available evidence of the impact of the rule,” explains Craig Aaron, president and CEO of the media industry watchdog group Free Press:

Net neutrality opponents talked about how internet infrastructure will suffer. But if you actually look at what the phone and cable companies are reporting to their own investors since 2015: They’re bragging about deployment, they’re talking about all the faster speeds they’re providing, they’re talking about doing more with less money.

In endorsing a return to the “light touch” status quo ante—which is itself a misreading of the agency’s regulatory history—Pai cites studies that show a slight dip in broadband investment since 2015. But that proof is notably funded by the telecom industry, and other reporting on companies like Comcastcontradicts his claims. So, like the widespread passage of draconian voter ID laws to combat a nonexistent epidemic of vote fraud, the Trump administration FCC’s justification for killing net neutrality is a right-wing “solution” to a phony problem. Aaron chalks up this FCC’s unwillingness to accept the truth as proof they don’t really care about consumers or the public interest. “To them, it really comes down to regulation is bad, and regulations passed by the Obama administration are worse.”

Even if motivated by partisan spite, the impact of losing net neutrality could be devastating for all news consumers and a free and independent press. With no legal or regulatory prohibitions stopping them, telecom companies and ISPs would feel emboldened—spurred on by their shareholders—to start picking and choosing one kind of content over another to maximize profits.

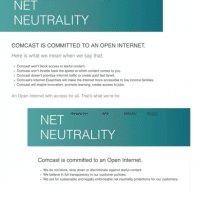

Comcast‘s net neutrality pledge, before and after the day (4/26/17) the FCC’s Ajit Pai announced his plan to scale back net neutrality requirements. (Ars Technica, 11/29/17)

Coincidentally, on the same day Pai announced his plan to roll back net neutrality last April, Comcast, the nation’s largest cable company and the owner of NBCUniversal, was caught subtly changing the language of its online net neutrality pledge. Before, the company promised to never offer “paid prioritization” (fast lanes) of Internet traffic; now it merely said it would not engage in “anti-competitive prioritization.” That vague, legalistic language amounts to a semi truck-sized loophole, ripe for abuse.

“There’s just so much incentive for a Comcast, which owns all these channels and movie studios, to give their own content a leg up and they can do it in ways that, as an end user, you might not know what’s going on,” Aaron points out.

For example, you might try to watch a Democracy Now!broadcast and you get that spinning wheel of death. It’s not loading, so unless you’re really committed to seeing it, you’ll probably go somewhere else, like NBC News, that loads quicker. That’s the kind of advantage they want. It’s like a big horserace, except they own the track and can give themselves a head start, and even if it’s only a few seconds in load time or a certain percentage in quality difference, that’s a big deal.

The backlash to the repeal has been ferocious. Just between Pai’s announcement in April and the end of August, the FCC received nearly 22 million public comments about the rule change. Most of these comments opposed the repeal: a Pew analysis found six out of the seven most prevalent comments supported net neutrality. And public polling also finds a majority of Americans prefer to keep net neutrality.

There was also a large-scale campaign of fraudulent FCC comments using 1 million stolen identities, which the FCC is refusing to help investigate. On the day before the repeal, 18 state attorney generals went public with a letter calling on Pai to delay the vote until the million-plus fraudulent public comments could be properly investigated.

Part of the overwhelming response can be attributed to comedian John Oliver, whose May segment in support of net neutrality went viral and has garnered more than 6 million views online. But the resistance runs far deeper than that.

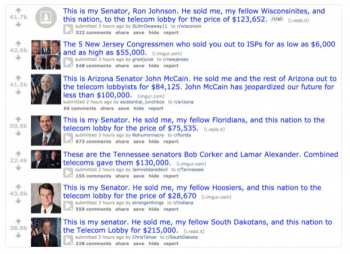

Reddit‘s front page, devoted to pointing out lawmakers who supported net neutrality–or sold it out. (image: Cory Doctorow, 1/11/17)

An open letter signed by more than 50 mayors of US cities, from New York City to Salem, Virginia, called on the FCC to abandon its repeal. On the same day Michael Flynn pleaded guilty, the entire front page of Reddit was devoted to supporting net neutrality and expressing outrage at industry-funded lawmakers who failed to support it. (Even in the r/NASCAR subreddit, the most upvoted story ever is now about the need to protect net neutrality.) Members of Congress have been deluged with calls and comments as well. During the week of Thanksgiving, Illinois Congressman Mike Quigley reported 4,204 constituent calls supporting net neutrality, 0 against. Even the “father of the Internet,” Vint Cerf, and numerous other tech leaders have spoken out in support of net neutrality.

“Net neutrality has become a new third rail,” Aaron says. “This is very much a political issue now.” Despite the broad grassroots opposition, not to mention the unanswered questions about the legitimacy of some of the FCC comments, Pai and his fellow Republicans on the commission pushed ahead and voted to end net neutrality anyway.

Gutting Big Media Accountability

“What Pai is doing is moving us to an anti-competitive, ‘pay to play’ system of the internet, one that makes it harder for citizen journalists who have a camera or a phone to report and compete with big media companies,” explains Phillip Berenbroick, senior policy counsel for the open internet advocacy group Public Knowledge. And a mostly overlooked element of this plan, Berenbroick adds, is Pai’s push to strip the FCC of its regulatory and enforcement duties.

“In effect, the FCC is trying to dump enforcement of the Internet onto the FTC, which is already overtaxed,” Berenbroick explains. Pai justifies this move as a step toward more accountability, and he often calls the FTC, which oversees everything from diapers to airlines, the “nation’s premier civil law enforcement agency.” This tough talk is just a ruse, however, and glosses over the fundamental weaknesses inherent in dumping the FCC’s enforcement responsibilities onto another agency. Even FTC commissioner Terrell McSweeny acknowledged back in April that his agency would not be as capable as the FCC at policing internet blocking or tiered-content prioritization.

First of all, Berenbroick points out that the FTC lacks deep institutional knowledge of the communications industry, making it unlikely to effectively deal with technical or legal issues that could lead to anti-competitive behavior by massive media corporations. The agency also has roughly 550 fewer employees than the FCC, and Trump has just proposed cutting its fiscal year 2018 budget to $306 million, $16 million less than the FCC’s.

Most importantly, the FTC can only enforce “unfair and deceptive trade practices.” In effect, it can only police companies after the fact for failing to live up to their own voluntary commitments. With legions of lawyers at their disposal, giant media corporations are unlikely to be swayed by consumer complaints of internet traffic discrimination when these same companies are able to write (and rewrite) the rules they’re supposed to follow.

Of course, the Trump FCC’s abdication of its regulatory duties is not surprising. One of Trump’s early telecom policy advisors, Mark Jamison, talked openly about eliminating the agency during last year’s presidential transition period. Just weeks before Trump’s election, Jamison had written an op-ed for the right-wing American Enterprise Institute, not-so-subtly titled: “Do We Need the FCC?” (Of note: Jamison previously advised cell phone corporation Sprint on regulatory issues.) In the post, Jamison claims one reason the FCC is no longer necessary is that “telecommunications network providers and ISPs are rarely, if ever, monopolies.” In fact, Pai’s predecessor, former FCC chair Tom Wheeler, pointed out in 2014 that four out of five Americans had only one choice for an ISP at basic broadband speeds of 25Mbps.

“The FCC, as the expert regulator of the communications industry, is far better positioned to deal with internet regulation, because it has the authority to write rules that prohibit bad behavior from happening in the first place,” Berenbroick notes. “If I were a cable company [Pai’s plan] is exactly what I would want.” For his part, Pai, a former lawyer for telecom giant Verizon, seems unconcerned about the appearance of bias. In fact, at a telecom industry dinner last week—hosted by Sinclair—the FCC chair joked about his “love” of his former company.

Wheeler, who led the fight to pass net neutrality, has likewise criticized the FCC’s efforts to dump enforcement on the FTC, calling it an “abomination.” In an op-edlast week, Wheeler noted the irony of such a move, since telecom giant AT&Trecently won a court case where it successfully argued that the FTC had no jurisdiction over its internet traffic activity.

Sensing the fury aimed at this naked surrender to industry, Pai released a joint Memorandum of Understanding just two days before the repeal about how the FCC and FTC would work together to monitor the internet. But the substance of the plan was little changed; it was little more than a blatant attempt at damage control. Democratic FCC commissioner Mignon Clyburn blasted it as a “confusing, lackluster, reactionary afterthought.” The repeal vote still happened, however. Because in the Trump era FCC, the prospect that multi-billion-dollar media conglomerates could fall through the cracks, and their online control over the nation’s news and information could go essentially unregulated, is more a feature than a bug.

Undermining Local Journalism

The damage wrought by this FCC doesn’t stop with repealing net neutrality, though. As that more public battle has raged, the agency quietly gutted media ownership rules last month, opening the door to even more local TV consolidation, which could have a catastrophic impact on news diversity and local journalism. “Net neutrality has gotten more attention, because consumers can better understand the idea of my Netflix feed slowing down and buffering if I don’t pay Verizon more for video streaming,” notes University of Delaware public policy professor Danilo Yanich. “But media consolidation suffers because it is an abstract concern for news consumers; it’s hard for viewers to be outraged about the stories your new local TV station doesn’t cover.”

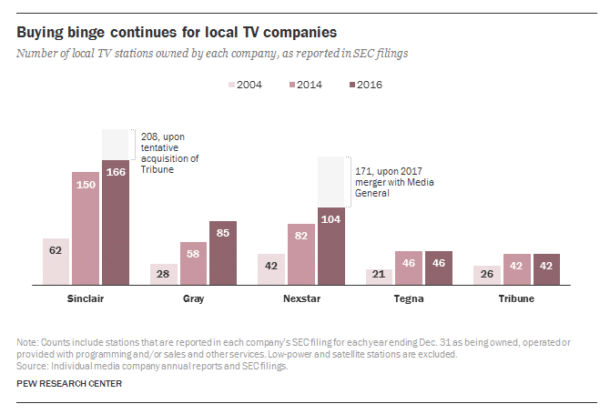

Companies like Sinclair, Gray and Nexstar have bought up hundreds of TV stations since 2004. (Chart: Pew, 5/11/17)

Local TV, which just a few years ago was considered a dying backwater, has become among the hottest properties in the media industry recently. Between 2013 and 2016, the local TV news industry saw more than $20 billion in mergers and acquisitions deals, with hundreds of stations changing hands. As a result, several dominant players, among them Sinclair Broadcasting and Nexstar, have emerged. According to a Pew Research Center analysis of BIA Kelsey data, by the time 2017 arrived, five companies owned 37 percent of all full-power local TV stations in the country. This has translated into $2 billion in additional revenue for these companies since 2014.

“The mantra from these big media groups now is ‘go big or go home,’” says Yanich.

Mergers create more leverage for local TV media groups to charge broadcasters and cable companies more money for retransmission. And the reason they can say that is because they now control dozens or hundreds of stations across the country.

But local TV has also turned into a lucrative cash cow thanks to the radically changed landscape of political advertising in the wake of the 2011 Citizens United ruling, he explains. After analyzing the finances of seven major TV station corporations, a Pew report found that their combined political ad revenue jumped from $574 million in 2012 to $696 million in 2014 to $843 million last year. And those numbers are projected to grow even more in the future.

“Local TV news remains an extremely important vehicle for political communication,” Yanich explains. That is, in part, because local journalism is the most trusted form of news. Currently, Yanich is working on a book studying the relationship between political ads and news content in the 2016 election. He notes that this trust factor, plus the fact that local TV reaches a large number of voters who aren’t hardened partisans, makes it an appealing target for political influencers. “So a lot of money will keep going into local TV for political ads in 2020, because that’s the best way to get the message across to these undecided voters.”

Greater media consolidation may be good for the bottom lines of local TV conglomerates, but it’s not good for journalism. “This has huge implications, and it’s going on in the backyards of America, but most folks don’t know it because it’s simply not covered,” Yanich says.

It’s certainly not covered in depth in the mainstream press. It might be covered by FAIR or industry journals, but a local TV station in Philadelphia is certainly not going to tell you about the duopoly it has with another local station. What it instead says is: “We are extending the reach of the primary station.”

That’s why the FCC’s under-the-radar accompanying decision to rescind the “main studio” rule is so damaging. Previously, local TV stations were required to maintain a newsroom in the communities they covered, the goal being to keep their journalism centered on local issues. But with the rule lifted, local TV giants are now free to gobble up more and more stations, and then shut down those newly acquired local newsrooms to pad their profits. They can then pipe in pre-packaged news produced in faraway studios to save even more money. “You end up with the same anchors, same videos, same narrative,” Yanich explains. “Coupled with the move to end net neutrality, more media consolidation will have the effect of squelching dissent, whether for ideological or commercial reasons.”

Former Trump and Sarah Palin advisor Boris Epshteyn is one of Sinclair‘s must-carry commentators (7/8/17).

Indeed, greater local media consolidation will make it much easier to manipulate the news to fit the agenda of a corporate parent. Nowhere is this more apparent than at Sinclair Broadcasting, the largest TV station owner in the country, which has a well-established track record of coloring its news to favor right-wing ideology. A recent example: Back in May, when Montana Republican Congressional candidate Greg Gianforte physically attacked a reporter on the eve of a special election, the local Sinclair affiliate refused to cover the story, even though numerous other news outlets did and a Fox affiliate witnessed and had an audio recording of the assault. Even more egregious, Sinclair forces its affiliates to run long, pro-Trump commentaries in its news broadcasts as many as nine times a week. Now Sinclair wants to bring this kind of broadcast mindset to even more of the country—in May, it proposed a massive acquisition of the fifth-largest local TV company, Tribune Media, which would give it more than 200 stations nationwide, and broadcast access to three out of four American homes.

The consequences for the homogenization and hollowing out of local and independent news are ominous. “As a viewer in a community, I’m better served if there are multiple newsrooms trying to hold public officials accountable. You want competing sources of information, different viewpoints and voices,” Free Press’s Aaron points out:

But if it’s all under the same corporate roof and literally produced by the same people, you can’t have that. In multiple communities right now, if you’re clicking through on Election Night, your local outlets might be simulcasting the same content on multiple channels.

The Fight Ahead

While this flagrant rollback of media consolidation rules looks unlikely to be reversed anytime soon under the Trump administration, net neutrality stands a better chance of being preserved. The political pressure on Congress to protect Title II internet regulation shows little signs of stopping. And numerous free press and civil liberties groups plan on suing the FCC to temporarily halt and, ultimately, reverse the repeal.

“We think this FCC completely botched the process. It has just ignored the public and never addressed the apparent fraud happening in the comments,” Aaron says. Likewise, the FCC’s public review simply disappeared the more than 50,000 consumer complaints lodged against internet providers since net neutrality went into effect. Notes Aaron:

When it comes to the FCC and administrative law, the fact that there is a new president, in and of itself, is not a winning argument for changing rules. There was a 10-year fight to get net neutrality, and then the decision was upheld in court. So here comes Ajit Pai who says, “Sorry, new sheriff in town, we don’t need any of it.” There’s a legal burden there to prove that. We will sue him, it will go to federal court and we like our chances.

That legal fight could take more than a year to reach a final resolution, almost guaranteeing that net neutrality will be a key campaign issue in the 2018 midterm elections. Republican Sen. John Thune has been at the forefront of this issue, publicly calling for a bipartisan, congressional fix to settle the open internet issue once and for all. Some media giants, like AT&T, have echoed his call for a legislative solution as well. But upon closer inspection, these Republican and corporate definitions of “open internet” would still shortchange consumers and make it harder on the independent press. No Democrats have signed on to sponsor his bill.

“We shouldn’t fall for a compromise that is 5 percent less awful than what the FCC is doing,” Aaron warns:

Senator Thune’s bill codifies basic internet protections, but strips the FCC of any ability to adjust or adapt to new abuses or tactics. It will also prohibit tactics the telecom and media companies don’t have any intention of doing anyway. They will call it “net neutrality,” but it will be a toothless version.

Getting the American public more involved in a real, transparent debate over net neutrality—along with a broader discussion of what kind of media and news environment we want to encourage—is critically important to the future of our country, says former FCC commissioner Copps. And it would stand in stark contrast to Pai’s cloistered approach, where he rarely ventures outside a friendly bubble of conservative think tanks and the airwaves of Fox News to tout his industry-first policies.

“The American people need to know what he wants to do, and he needs to really hear what the American people think,” Copps says of Pai. The former FCC commissioner points to two dark forces at work right now gaining ever greater control over our national discourse: the power of big money and big media, and an extreme, right-wing ideology that thinks an unfettered free market is the cure for all evils.

“We have this technology that has the potential to be the town square of our democracy, but this FCC is setting up fewer and fewer, huge gatekeepers to that,” he says. As a result, cherished ideals like freedom of expression and freedom of the press are now under threat from a Trump administration that prioritizes multinational telecom and corporate media profits above all else. “Big media sees you and me and all the people in the United States not as citizens,” Copps says, “but as products to be delivered to advertisers.”