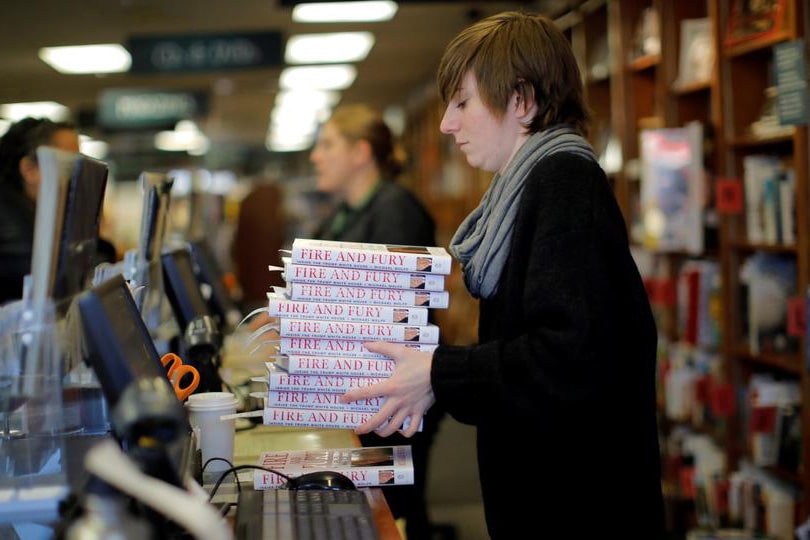

The extraordinary media attention directed at journalist Michael Wolff’s book Fire and Fury: Inside the Trump White House (Henry Holt, 2018)—heightened by Trump’s own attacks on Wolff’s book—has merely brought out into the open what was already obvious, namely that all of Trump’s closest aides consider him mentally unstable, narcissistic, incompetent, uninformed, and dangerously ill-equipped to be president. The general picture is of a West Wing rife with infighting and general chaos, particularly in the first 100 days when the Bannon/Breitbart and what Wolff calls the “Jarvanka” (standing for Jared Kushner and Ivanka Trump) factions were perfectly free to square off against each other. In the midst of all of this turmoil was Russiagate, which, however, Wolff to his credit recognizes, is mainly a distraction, when compared to the emerging new forces in U.S. politics.

Indeed, more important than the discord in the White House and the clownish behavior of POTUS or the disdain with which he is viewed by his closest aides, is what Wolff’s Fire and Fury reveals about the deeper crisis of U.S. capitalism and the body politic—but which is ignored in most media accounts of the book. Here the elephant in the room is not Trump himself but the nationalist-populist movement that brought him to power (identified with his supposed solid political base of 35 percent of the population) and that now seems to be escaping his grasp. This is the real argument that unifies Wolff’s book. It is the reason he places so much emphasis on Charlottesville and the neo-Nazi Richard Spencer.

The term “nationalist-populist,” which gains a kind of strength or spectral quality from its obvious association with “nationalist-socialist,” has a long currency in Europe as a way of designating movements that are within the fascist genus, especially those of the neofascist ilk.1 Bannon—who is an admirer of Julius Evola, the Italian fascist theorist who advised both Mussolini and Hitler and then became the leading postwar exponent of neofascism—introduced into Breitbart and the right-wing discourse in general the designation “nationalist-populist” to describe the new alt-right movement.2 The intent was clearly to get away from the term “populist,” which the liberal-democratic establishment was using to describe grassroots movements of both the left and the right (casting aspersions on both). For Bannon, the consummate neofascist strategist, this new designation was necessary to make clear the hard right, neofascist character of the emerging political movement, in which he regarded Trump as a mere “vessel” (176).

Wolff fails to connect all of the dots with respect to the rise of the nationalist-populist movement, but nonetheless has a clear instinctive sense of what is happening. His book is explicitly structured throughout around the Trump and Bannon relationship/conflict, and the contest for leadership of the nationalist-populist movement. As in a dime novel readying the reader prepared for the next outrageous installment, Wolff concludes with Bannon’s plans to take the movement away from Trump and to propel it in a more incendiary direction. What is at issue here is the “deconstruction of the administrative state” as originally envisioned by Trumpism’s most extreme nationalist-populist adherents. As Wolff writes, “Asked about Trump’s leadership of the nationalist-populist movement, Bannon [in October 2017] registered a not inconsiderable change in the political landscape: I am the leader of the nationalist-populist movement” (301).

Trump is a financial capitalist who is also nationalist, racist, and authoritarian. But he does not read. As Wolff tells us anything in print has no existence for him. He has no real ideas and no strategy of his own beyond an innate cupidity, a kind of media savvy, and a sense of being able to act with impunity. Wolff reminds us, that it was Bannon who wrote, with his Breitbart colleague and Trump senior adviser, Stephen Miller, Trump’s nationalist-populist inaugural address; who articulated the goal of the “deconstruction of the administrative state”; who conceived the anti-Islamic immigration orders; who was behind Trump’s attempt to identify himself with Andrew Jackson; who was the strongest proponent of leaving the Paris Climate Accord; and who argued that geopolitically the main goal had to be to challenge China if the United States was not to face an economic apocalypse. Most importantly, it was Bannon—whose favorite paper, according to Wolff, is the left-liberal Guardian in the UK, which he puts to his own alt-right purposes—who recognized that the U.S. was in economic crisis and decline (276). He was therefore able to bring to bear a sophisticated white lower middle class, racist ideology—which Trump benefited from and innately represents but could hardly be said to understand. Wolff quotes Bannon as saying that “He [Trump] gets it” with regard to the neo-fascist program, and then immediately qualifying this by saying “Or he gets what he gets” (6). At the end of Wolff’s book Bannon is seen as standing alone, challenging Trump’s leadership of the national-populist (neofascist) movement by promoting a Cro-Magnon right against establishment Republican candidates, beginning with his support of Roy Moore in Alabama.

Wolff, though hardly an admirer of Bannon, clearly subscribed to the latter’s assessment in Fall 2017 that Trump had a one-third chance of being impeached, a one-third chance of being removed by his own cabinet on the grounds of incompetence and mental instability via the 25th amendment, and a one-third chance of making it somehow to the end of his term. Trump, in Bannon’s assessment, had a zero chance of making it to a second term (309). The supposed 35 percent of the electorate that were steadfastly loyal to Trump, Bannon insisted, would embrace a more authentic national-populist leadership leaving Trump himself behind. Regardless of what transpired in the White house the neofascist movement would continue to grow. Bannon even mentioned to Wolff the possibility of his own presidential campaign (which he said would be backed by hard right billionaires like Robert Mercer—which ended up angering Mercer and causing him to declare he was cutting off his support for Bannon). As Wolff ominously concludes his book:

Trump, in Bannon’s view, was a chapter, or even a detour, in the Trump revolution, which had always been about the weaknesses of the two major parties. The Trump presidency—however long it lasted—had created the opening that would provide the true outsiders their opportunity. Trump was just the beginning.

Standing on the Breitbart steps, that October morning, Bannon smiled and said: “It’s going to be wild as shit” (310).

This is the real story of Wolff’s Fire and Fury, ignored by an establishment media that has no interest in revealing anything about the class struggle. Moreover, the danger is much greater than an opportunistic, maverick liberal journalist like Wolff, however streetwise, is able to grasp. As I wrote in the conclusion to Trump in the White House:

There is little doubt that Breitbart and Bannon represent the rise of a full-fledged neo-fascist politics. Indeed, the rise of the radical right as the most combative sector of Trumpism helps us to situate Trump himself, based on the old adage that you can judge people by the company they keep. Bannon, as Trump’s campaign manager and chief White House strategist, master-minded a neo-fascist, that is racist, ultra-nationalist, patriarchal, and financial-capitalist path to power, well in keeping with Trump’s own views. Moreover, Bannon and other Breitbart figures in the Trump White House demonstrate considerable knowledge of and affinity for today’s transnational neo-fascist movements emerging in Europe.

Trumpism is thus not to be regarded as an accidental or ephemeral movement—regardless of the eventual political fate of Trump himself, who is presently beleaguered by Russiagate investigations throwing the future of his administration into question. The neo-fascist monster, once released on the world, will not easily go away. Rather it is a definite manifestation of the crisis of the U.S. imperial economy, emanating both from the deepening stagnation of monopoly-finance capital and the gradual erosion of U.S. economic hegemony.3

It should be clear by now that Trumpism is a disease of the society, not a personality fault confined to one or two individuals—a view that even Wolff at times seems prone to holding. In the midst of the structural crisis of capitalism associated with neoliberalism, and the growing instability of its ever more onerous rule, key sectors of capitalist class have taken a hard right turn and has unleashed the largely white lower-middle class (also subsuming some of the more privileged sections of the working class), with its nationalist, racist, patriarchal, and anti-establishment liberal politics, as its rearguard defender, with the object of a blitzkrieg attack on the U.S. domestic population. Ultimately, as in all movements of the fascist genus, the main beneficiaries will be monopoly capital (today monopoly-finance capital) while the neo-fascist lower middle class foot soldiers will experience betrayal after betrayal. In many ways this resembles the old slavocracy and continual betrayal of the class of poor whites, who nonetheless defended the plantation system. Here Bannon’s instinct that Trump was Andrew Jackson holds true—but this time as both tragedy and farce.

Fascism—today neofascism—emerges in a capitalist system in crisis, and is the ultimate recourse of the capitalist class . To stop today’s nationalist-populist movement, bankrolled by what Bernie Sanders calls the “billionaire class”—against which mainstream liberals only raise a faint-hearted response, limited by their loyalty to the system of possessive individualism—requires nothing less than a volcanic eruption of the anti-capitalist left, rooted in a working class aimed at re-occupying the society as a whole.

Notes

- ↩ Walter Laquer, Fascism: Past, Present and Future (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 7, 201.

- ↩ John Bellamy Foster, Trump in the White House (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2017), 33-34, 66-71, 77; Steve Bannon, “All Citizens of All Backgrounds are Part of the Nationalist-Populist Movement,” Breitbart, September 10, 2017.

- ↩ Foster, Trump in the White House, 114-15.