A study last year by London University academics highlighted the shocking disparities in pay between individuals from different backgrounds. Most other papers treated this as minor news or ignored it altogether. The Morning Star rightly put it on the front page under the headline Working Class? That’ll be Six Grand off your Salary (and it was the only paper to mention TUC general secretary Frances O’Grady’s call for worker representation on company boards).

The study found that people from working-class backgrounds who get a professional job are paid an average of £6,800 (17 per cent) less each year than colleagues from more affluent backgrounds.

Even when they have the same educational attainment, role and experience, as their more privileged colleagues, those from poorer backgrounds are still paid an average of £2,242 (7 per cent) less. Women and ethnic minorities face an additional earnings disadvantage.

But it’s important to distinguish between the sociologist’s “social class” from economic class. They are often confused. Social class is a hierarchical division of individuals (at its crudest, “upper,” “middle” and “lower” class) according to their income, occupation, lifestyle, or tastes.

That sociological division is the one usually taught in schools and universities and assumed in the media, for whom the term “working class” is reserved mainly for those who work by manual labour—making or handling things in factories and shops or who correspond to the stereotypes presented in television in programmes such as Benefits Street. Prejudice then justifies widening social inequality. This approach is subjective and confused. For example the creative industries—music, art, theatre, etc—are usually excluded.

Economic class is something different. It refers to people’s relationship to capital and the means of production—how goods and services are produced, what happens to their value, and who controls and profits from the process.

It’s a relationship to power that people experience, not a label to be attached to individuals. Economic class is fundamental to society and to how power functions.

The data reported by the Star used a sociological definition of class based on data from over 60,000 individuals classified by the job of their main earning parent (80 per cent of them fathers) using the government’s seven main occupational groupings.

Managerial and professional jobs refer to classes one (company directors, doctors, lawyers, etc) and two (teachers, nurses, journalists). Classes six and seven refer to “semi-routine” (care workers, receptionists) and “routine” occupations (bar staff, cleaners, bus and lorry drivers, labourers). In between, classes three to five include police officers, secretaries, shopkeepers and small employers, electricians, train drivers and chefs.

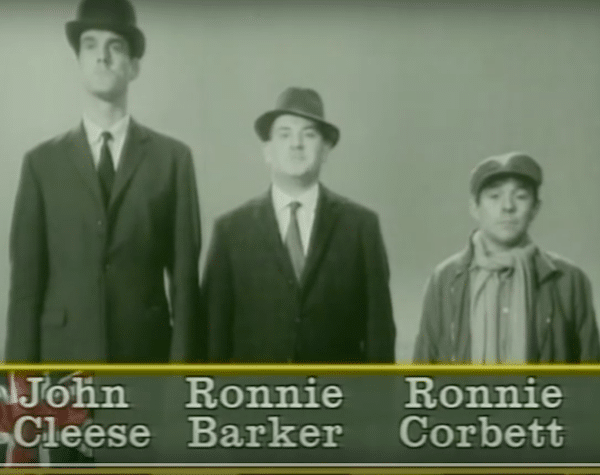

Britain has been described as a “class-ridden society,” far more socially stratified than most other European states. It was satirised by a famous sketch from the 1960s starring John Cleese, Ronnie Barker and Ronnie Corbett as upper, middle and lower class.

Upper-class Cleese looks down on Barker and Corbett. Middle-class Barker looks up to Cleese but down to Corbett. Working-class Corbett, looking up to Barker and Cleese, says merely: “I get a pain in my neck.”

Social class can be a source of prejudice and discrimination. The study reported in the Star used the term working class for those whose parents’ jobs were routine or semi-routine. It uses the term middle class just once (without defining it) to refer to the subtle processes of favouritism or cultural-matching, whereby elite employers misrecognise social and cultural traits they are familiar with as signals of merit and talent.

Opposing this prejudice is important. The report (funded by the government’s Social Mobility Commission) begins by quoting Theresa May’s pledge in her maiden speech as Prime Minister: “We won’t entrench the advantages of the fortunate few, we will do everything we can to help anybody, whatever your background, to go as far as your talents will take you.”

Most of U.S. would say “if only” to that. However, while confronting class prejudice is important, it doesn’t of itself pose any threat to exploitation. On its own it does not challenge core power relationships within capitalism.

Indeed, the lip-service paid by neoliberal politicians like May to improving social mobility reflects their desire to enhance “efficiency” (and labour competition) in key market sectors.

And the “sociological” approach to class—the way it is presented in the media and popularly used—is often divisive, implying that middle-class teachers (for example) do not have a common interest with other workers in building a better world. They do.

From an economic perspective, the working class constitutes all those who have to sell their labour power by hand and brain (the two cannot be separated) in order to subsist and who don’t exploit the labour of others.

There are grey areas of course. Wayne Rooney’s salary at Manchester United topped £15 million a year—around £300,000 per week—though it’s reportedly gone down a bit since joining Everton.

He’d probably be labelled “working class” by a sociologist but with an £82m fortune he arguably doesn’t have to sell his labour any more. And, as pointed out in earlier answers, while the boards and remuneration committees of Britain’s top companies claim that their CEOs (who each receive an average of £5.5m a year, some 130 times more than their employees) “earn” their pay, their work is focused not on producing use-value but on maximising profit and is directly exploitative of their workers.

Social progress requires challenging all prejudice, discrimination and favouritism based on social class, gender, ethnicity or identity, wherever it exists. That is right in itself.

It is also an essential part of enabling people to develop an awareness of their own economic class position—whatever their occupation and whether they are in full or part-time work, self-employed, carers or unemployed—and of the need for collective action.