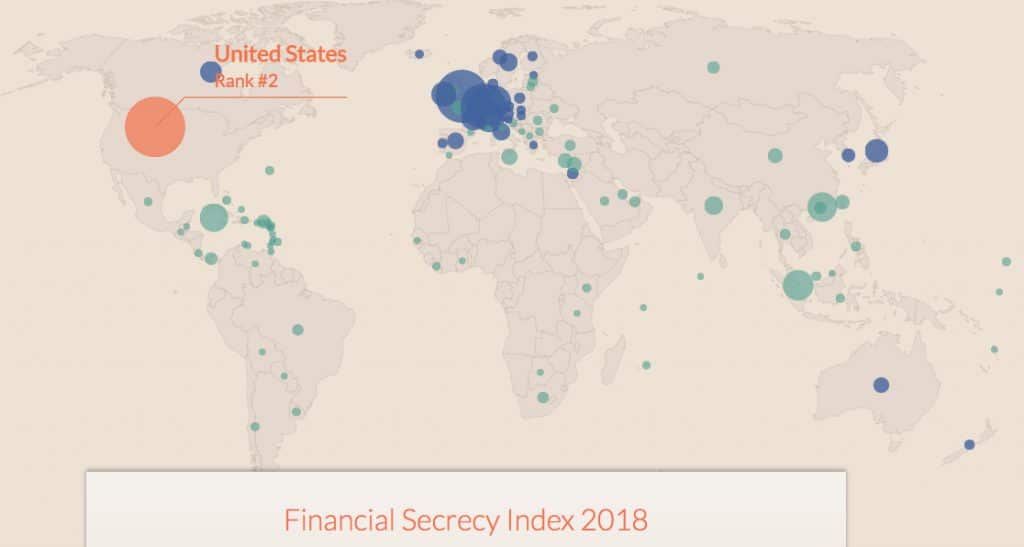

According to the Tax Justice Network, the United States ranks second in the 2018 Financial Secrecy Index. This is based on a secrecy score of 59.8, which is practically unchanged from 2015. The only country ahead of the United States is Switzerland, with a secrecy score of 76. The rise of the United States continues a long-term trend, as the country was one of the few to increase their secrecy score in the 2015 index.

According to the Tax Justice Network, the United States ranks second in the 2018 Financial Secrecy Index. This is based on a secrecy score of 59.8, which is practically unchanged from 2015. The only country ahead of the United States is Switzerland, with a secrecy score of 76. The rise of the United States continues a long-term trend, as the country was one of the few to increase their secrecy score in the 2015 index.

The continued rise of the United States in the 2018 index comes on the back of a significant change in the U.S. share of the global market for offshore financial services. Between 2015 and 2018, the United States increased its market share by 14 percent. In total, the United States accounts for 22.3 percent of the global market in offshore financial services.

So, actually, we’re #1!

History

The United States has long been a secrecy jurisdiction or tax haven at the federal level. For example, the 1921 Revenue Act exempted interest income on bank deposits owned by non-U.S. residents, and this was explicitly justified at the time as a measure to a attract (tax-evading) foreign capital to the United States.

Another factor influencing policy makers later on was the Vietnam War, which opened up growing external balance of payments deficits—after a long history of surpluses. The United States increasingly needed foreign loans to finance these deficits and it did so, in significant part, by a attracting the proceeds of tax evasion and other illicit foreign money. Foreigners invested in the United States for many reasons, not least the fact of the U.S. dollar being the global reserve currency—but secrecy and tax-free treatment were also key attractions.

Alongside this history of U.S. federal-level secrecy, individual U.S. states have been hosting the formation of secretive shell companies—especially as several states (such as Delaware, Wyoming, and Nevada) have engaged in a race to the bottom to outbid one other in offering ever more egregious secrecy facilities.

Here is how it works. A wealthy Ukrainian, say, sets up a Delaware shell company using a local company forma on agent. That Delaware agent will provide nominee officers and directors (typically lawyers) to serve as fronts for the real owners, and their details and photocopies of their passports can be made public but that gets you no closer to who the genuine Ukrainian owner of that company is: if the nominees are lawyers they are bound by attorney-client privilege not to reveal the information (if they even have it: the owner of that shell company may be another secretive shell company or trust somewhere else). The company can run millions through its bank account but nobody—whether domestic or foreign law enforcement—can crack through that form of secrecy in any efficient or effective way.