Here is a short version of a paper presented at the 9th Australian International Political Economy Network (AIPEN) Workshop, 8–9 February 2018 at Monash University, Melbourne.

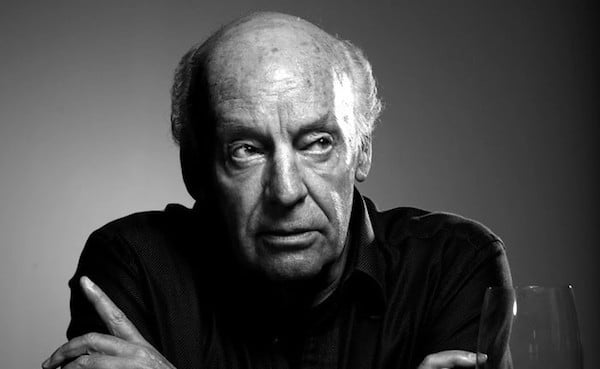

Uruguyan novelist and historian Eduardo Galeano (1940–2015) wrote more than 40 books. Monthly Review lauded his creative non-fiction Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent (1973[1971]) as ‘outstanding political economy … and perhaps the finest description of primitive capital accumulation since Marx’. More than one million copies were sold, translations appearing in many languages as it became a classic in history, geography, literature, and cultural and ethnographic studies (Rohter 2014).

Uruguyan novelist and historian Eduardo Galeano (1940–2015) wrote more than 40 books. Monthly Review lauded his creative non-fiction Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent (1973[1971]) as ‘outstanding political economy … and perhaps the finest description of primitive capital accumulation since Marx’. More than one million copies were sold, translations appearing in many languages as it became a classic in history, geography, literature, and cultural and ethnographic studies (Rohter 2014).

In Open Veins, Galeano traces a rapacious history of dispossession as capital’s soldiers and managers fractured the continent into territories and nations, and named the whole ‘Latin America’, an exotic trading playground in which Indigenous peoples almost always lost. They lost soil and minerals, they lost their cultures and virginity, they lost their languages, forms of governance and Indigenous sensibilities — all for the global accumulation of capital centralised in Europe and North America.

Galeano reports on this half-millennium-long history in ethnographic detail and with journalistic flair, embroidering narratives where money drives the plot. Cyclic seasonal and natural rhythms of Indigenous cultures are challenged by a linear workday clock time of offices, machinery and stock exchanges. The perpetual abstract growth of money as capital concretely meant expansive exploitation of landscapes and human energy.

Galeano had a multicultural working-class background, drifting into journalism to become an internationally renowned and awarded author of insightful non-fictional analysis featuring elements of magical realism. He revealed how it feels for Latin Americans to live within, alongside and in conflict with capitalism. His space was glocal; he read the present as an embodiment of the past. ‘By saying no to the freedom of money,’ wrote Galeano (1992, 244), ‘we are saying yes to the freedom of the people: a mistreated and wounded freedom, a thousand times defeated as in Chile and, as in Chile, a thousand times arisen.’

Witmer (2006, 1) has described Galeano’s Voices in Time (2006[2004]) as a ‘fluid mosaic’ of hundreds of ‘prose poems’. Indeed, many of Galeano’s books comprise short-short stories, which cascade into collages of meanings, communities and neighbourhoods of being. These short-short stories are cells with internal and external dynamics, in and for themselves while contributing to the whole just as leaves, fruit, bark and roots constitute a tree. Not only does his work show discipline in selecting precise and appropriate words but also a film editor’s concern with carefully cutting from this and that scene in order to compose a well-paced documentary-style logic in his narrative.

Nonmarket socialism

Five years before he died, Galeano agreed to a complied selection of extracts from previous works appearing as a chapter in a nonmarket socialist collection, Life Without Money: Building Fair and Sustainable Economies (published late 2011). Yet the book was bereft of this richly textured chapter. When the co-editors came to clearing permissions, the Galeano chapter was pulled due to complicated copyright agreements with seven publishers and a standard clamp on electronic reprints.

Nevertheless, drawing on the un-published draft of this chapter, one finds that Galeano’s attacks on the market and vision of a community-based mode of production point to a form of socialism centring on use values, participatory governance and direct democracy, i.e. nonmarket socialism. Galeano’s work is consistent with nonmarket socialist visions — and strategies for a socialist transition — that dispense with the state and the market, thus avoiding monetary values and relations, undercutting props of class in monetary exchange, cutting capital off at its knees, and developing substantive participatory democracy.

Nevertheless, drawing on the un-published draft of this chapter, one finds that Galeano’s attacks on the market and vision of a community-based mode of production point to a form of socialism centring on use values, participatory governance and direct democracy, i.e. nonmarket socialism. Galeano’s work is consistent with nonmarket socialist visions — and strategies for a socialist transition — that dispense with the state and the market, thus avoiding monetary values and relations, undercutting props of class in monetary exchange, cutting capital off at its knees, and developing substantive participatory democracy.

No-one else has drawn attention to this nonmarket socialist reading of Galeano but it explains why, close to his death, he described Open Veins as ‘badly written’ and the text so ‘extremely leaden’ that ‘my physique can’t tolerate it’. But this did not equate with renouncing socialism — as was widely speculated — but rather highlighted his rejection of the mainstream socialist approaches of many political economists and populist politicians. (Rohter 2014)

Indeed, Galeano’s ‘community-based mode of production’ is consistent with anti-politics calls for commons, participatory democracy and sharing economies. He is much closer to the Marx who railed against Proudhon and Owenists than to the actually existing socialism of Castro and Cuban statism. Thus, Galeano would criticise Soviet communism by saying: ‘[S]ocialism is not dead because it hasn’t been born. It’s something I hope that humanity may perhaps find.’ (Potosi 2003: 7)

Galeano’s contribution to nonmarket socialism

Galeano’s work certainly expresses a nonmarket socialist analysis in his strong appreciation of the world of use values. His black humour and cinematographer-like point of view clearly define a highly ideological appearance-world of exchange values — price, profit and speculation. In Upside Down: A Primer for the Looking-Glass World (2001) the world of exchange values is thrown into stark relief by the everyday search to fulfil basic needs with real use values and the struggle to maintain an Indigenous reverence and stewardship of nature.

While mocking exchange values and monetary capitalist structures that contort social and environmental values, Galeano’s analysis strips our world back to the essentials of use values, implying more straightforward, efficient and effective dynamics of balance and sustainability. Galeano continually points to the absurdity and vacuity of excessive consumption and reveals, instead, qualitative and experiential realities. His socialist vision requires re-growing the human and humane, the natural and ecological, a world of synergies with Indigenous, diverse and mega-natural relationships and values.

He shows the absurdity of private property in Indian perspectives: ‘The land has an owner?’, but ‘We are its children … it nurtures us … It looks after us … How is it to be sold? How bought?’ (Galeano 1987, 225) Thus, Galeano calls for the restitution of local sustainability in a timeless and time-full approach: ‘It’s out of hope, not nostalgia, that we must recover a community-based mode of production and way of life, founded not on greed but on solidarity, age-old freedoms and identity between human beings and nature.’ (Galeano 1991)

Instead, the standardisation of humanity characteristic of globalisation is a dominating force that unifies space and time in ‘a sort of massacre of our capacity to be diverse, to have so many different ways to live life, celebrate, eat, dance, dream, drink, think, and feel.’ (Galeano in Potosi 2003: 7) Such insights support visions and strategies of nonmarket socialism that embody diversity, security and plenty just as much as a space full of spaces and a time full of times.

In short, Galeano seamlessly blends that people and planet caring approach central to postcapitalism, offering a language and images of a nurturing and abundant nonmarket socialism. He binds the tragedy of the Global South with the Global North casting both as deplorable. He attacks our disabling politics — stuck in economic domination.

Galeano’s passion and politics remind that we cannot build socialism from political economy or straightforward traditional left politics. It is a cultural process of becoming, through practices that revalue social relationships and nature in terms of qualitative — not quantitative — minimalism and efficacy. Galeano shows that another mode of production exists today, in this space in this time, in embryo.