Significant efforts are under way to curb alleged fake news and Russian propaganda in the Western hemisphere. This campaign has been accompanied by policies aimed at censoring alternative news organizations and dismantling net neutrality regulations. In my new book Media, Propaganda and the Politics of Intervention (New York: Peter Lang, 2017), I demonstrate, on the basis of a study of US, UK and Germany national newspaper reporting of contemporary conflicts, that the Western mainstream news media actually constitute major providers of biased news. In the last several decades, news media have engaged in a selective discourse of shaming accompanied by devastating military interventions. For anyone seriously concerned about fake news and propaganda, the mainstream news media—rather than the few independent or Russian media outlets reaching Western audiences—should be the major focus.

Fake news by design

Extensive empirical evidence from academic research confirms that due to their institutional design, the mainstream news media have been highly supportive to economic and political power. Just consider the following selected findings:

- Research suggests that Western journalists are hardly able to scrutinize existing capitalist social arrangements, and particularly the unjust class nature of so-called liberal democracies: A classic study by Warren Breed highlighted how journalists at a mid-sized U.S. newspaper abided by policy of a “covert nature” which was internalized as a “pattern of control through reprimand” (pp. 328-329). Executives and veteran staffers mainly enforced this policy in the newsroom. Policy pressures were so determining that they overrode the “personal beliefs” and “ethical ideals” of rank and file journalists (p. 332). Crucially, adherence to newsroom policy translated into slanted news media performance: “For the society as a whole, the existing system of power relation-ships [sic] is maintained. Policy usually protects property and class interests, and thus the strata and groups holding these interests are better able to retain them.” (p. 334) (see Warren Breed, Social Control in the Newsroom: A Functional Analysis. Social Forces, 33(4), 1955, pp. 326-335.)

- Accordingly, the researchers of the Glasgow University Media Group found that journalists believed they were “independent and critical” but at the same time the Group’s studies on television coverage showed how news tended largely to “follow ‘official’ explanations and to justify these in reporting.” (p. 5) (see Glasgow University Media Group, War and Peace News (London: Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1985).

- One of the most consistent findings in journalism studies has, thus, been that official sources and perspectives dominate the news: The U.S. scholar W. Lance Bennett coined the widely cited “indexing” norm according to which news media largely parrot government discourses. As Bennett (p. 106) observed, professional journalists “tend to ‘index’ the range of voices and viewpoints in both news and editorials according to the range of views expressed in mainstream government debate.” As a consequence of the application of the “indexing” norm, non-official sources and critical angles are only incorporated in news and editorial coverage if they are congruent with judgements already expressed in political officialdom (see W. Lance Bennett, Toward a Theory of Press-State Relations in the United States. Journal of Communication, 40(2), 1990, pp. 103-125).

- Elite “indexing” may lead to heavy news media criticism of state managers if there is political conflict within or between parliament, the secret state and the business community. On the one hand, this is exemplified by coverage of U.S. President Donald Trump: News media have scrutinized those aspects of Trump’s presidency that affected sectional elite interests or shed a negative light on the U.S. empire. On the other hand, work by David Edwards and David Cromwell of Media Lens has shown that militarist policies enacted by the Trump administration have not been sufficiently scrutinized because they are congruent with longstanding policies that hold bipartisan support in Washington.

- A more subtle connection exists between intelligence services and the news media. Richard Keeble argued, “while it might be difficult to identify precisely the impact of the spooks…on mainstream politics and media, from the limited evidence it looks to be enormous. As Roy Greenslade, media blogger at the Guardian and editor of the Mirror at the time of the Gulf crisis in 1991, commented: ‘Most tabloid newspapers—or even newspapers in general—are playthings of MI5.’” (p. 35) (see Richard Lance Keeble, Covering Conflict: The Making and Unmaking of New Militarism [Bury St Edmunds: Abramis, 2017]).

- Most liberal democracies institutionalized the “free-market” economic model in the early 20th century. Aside from public service providers like the BBC (which are subject to other constraints), almost all news publishers including “quality” newspapers like the New York Times, the Washington Post, or the Guardian, depend on corporate sponsorship by way of advertising funding. Additionally, news media are controlled by wealthy owners and shareholders and have to operate cost-effective in the market system. As a resulting implication, the mainstream news sector has to support the core interests of the business community whose members act as their sponsors. Thomas Ferguson (p. 400) described the resulting implications: “…major media…controlled by large profit-maximising investors [i.e. owners, advertisers, share holders] do not encourage the dissemination of news and analyses that are likely to lead to popular indignation and, perhaps, government action hostile to all large investors, themselves included.” (see Thomas Ferguson, Golden Rule: The Investment Theory of Party Competition and the Logic of Money-Driven Political Systems [Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press]).

- Consequently, many issues of importance for Western populations will not be featured in the narrow spectrum of mainstream news media reporting. Benjamin I. Page defined such occurrences, when news media exclude issues favored by large segments of the population, as “elite-mass gaps” (p. 118). According to Page: “On some issues these gaps are so great that public discourse, as articulated by officials, experts and journalists, may be quite distant from the values and concerns of ordinary citizens.” (pp. 118–119) (see Benjamin I. Page, (1996) Who Deliberates? Mass Media in Modern Democracy [Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1996].)

- Digital technology potentially allows for diverse information flows. But as Robert W. McChesney has argued in his book Digital Disconnect, the major institutional environment of the old media system has remained intact in the internet age. During the mid-1990s, and as a result of political decision-making, the public-service aspects of the internet were “privatized” and transformed into a “free-market” commodity—much to the discomfort of the scientists who had created the technology with public money. Since “privatization” was institutionalized, advertising funding has become the major driving force of internet technology development. Hence, the core function of today’s digital communication system is user-data-tracking. Online advertising has, thus, opened the floodgates for global mass surveillance by commercial companies and intelligence services. Furthermore, monopoly corporations, closely tied to Western state interests, have effectively colonized the online environment. Additionally, most major online news organizations are either offshoots of powerful corporate legacy providers or are tied to wealthy sponsors. (see Robert W. McChesney, Digital Disconnect: How Capitalism is Turning the Internet Against Democracy [New York: The New Press, 2013]).

Major academic studies, thus, suggest systematic bias—call it fake news or propaganda by design—in the mainstream news media.

Manufactured bloodbaths and military intervention

Building on the Herman-Chomsky Propaganda Model, and some of the studies outlined above, the empirical research in my book assessed how the US, UK and German national press consistently applied double standards in their reporting on bloodbaths associated with so-called “enemy” states as opposed to similar incidents carried out by Western states and their “allies”. Bloodbaths related to “enemy” states served an important public relations function in the pursuit of Western strategic interests. The news media highlighted and scrutinized “enemy” bloodbaths, even if event specifics were contested and hard to verify. The news media also provided a platform for Western officials and interest-party sources to convene about potential reactive measures such as military intervention.

Dismantling Libya

From February 2011 onward, then-Libyan Head of State Muammar Gaddafi’s security forces clashed with protestors in a range of Libyan cities from Benghazi in the East to the capital in Tripoli. The Western news media framed these events as major regime-crackdowns against protestors. The news media generously provided space for officials from US, UK and EU governments, Western experts as well as spokespersons from Libyan opposition groups and defectors. In concert, these voices demanded substantial political and military measures to stop the actions of the Libyan government including military intervention by way of an enforcement of a no-fly zone. Incidentally, this discourse was in alignment with similar calls by affiliates of the Brookings Institution, an organization which, according to academics John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt, was “part of the pro-Israel chorus,” as well as an appeal demanding the implementation of the Responsibility to Protect doctrine (R2P), published by the pro-Israel NGO UN Watch.

A major argument of this campaign was that Gaddafi’s air and security forces would have indiscriminately targeted protestors. For instance, on 25 February, an item in The New York Times by Helene Cooper and Mark Landler mentioned “American officials” who were “discussing a no-flight zone over Libya to prevent Colonel Qaddafi from using military aircraft against demonstrators.” Similarly, on 28 February, the Guardian’s Julian Borger, Patrick Wintour and Martin Chulov reported that then-British Prime Minister David Cameron “had told the Ministry of Defence and the chief of the defense staff to draw up plans for a no-fly zone in coordination with Britain’s NATO allies.” The journalists said such policy “would be designed principally to prevent attacks on Libyan people by the Gaddafi regime—mainly by his helicopter gunships.”

Yet, Libyan government atrocities could not be independently corroborated. First of all, Western journalists hardly had access to the theater. As the Independent’s Catrina Stewart and Kim Sengupta wrote on 21 February: “The picture in Libya is at times confused. Foreign reporters have been barred from the country, and the authorities have periodically blocked access to the internet.” (Gaddafi regime: We will fight to the end, 21 February, pp-1-2) Secondly, the narrative that Gaddafi’s air force targeted protestors had quickly collapsed. On 2 March 2011, a report by the Washington Post’s Karen DeYoung and Craig Whitlock referred to Robert Gates, then-US Secretary of Defense, and Admiral Mike Mullen, then-chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, who “told reporters that they had no confirmed reports that Libyan leader Moammar Gaddafi had used airstrikes against civilians or opposition forces that occupy the eastern half of the country.” However, this high-level testimony was only cursory reported and did not change the overall tenor of the press.

Thus, on 17 March 2011, about one month after the first reports on the Libya “crackdown” had been published, the United Nations Security Council authorized a NATO intervention as a consequence of which the Gaddafi regime was dismantled. This so-called “humanitarian intervention” was far more deadly than the violence that had preceded it. According to one scholarly estimate by Alan J. Kuperman, “NATO intervention magnified the death toll in Libya by about seven to ten times.” (p. 123) (see A Model Humanitarian Intervention? Reassessing NATO’s Libya Campaign. International Security, 38(1), 2013.) The same study also suggested that Libyan security forces had not indiscriminately targeted protestors during the clashes (see pp. 108-113). This finding was broadly confirmed by a report of the UK Parliament’s House of Common’s Foreign Affairs Committee, published on 9 September 2016. Yet, at this point in time, the political, social and economic fabric of Libya was crumbling.

In conclusion, NATO rather than Gaddafi had administered a bloodbath in Libya in 2011. While Gaddafi’s “crackdown” against protestors was manufactured, the mainstream news media would largely ignore the fact that NATO actions had actually led to the dismantlement of the Libyan state.

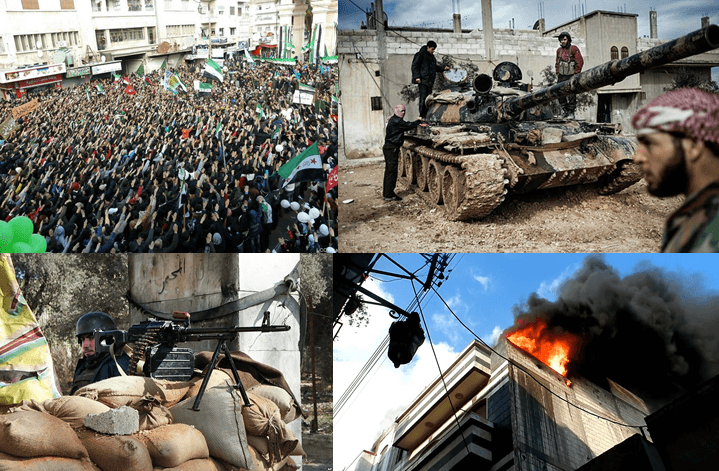

Destabilizing Syria

When covering the Syrian War that erupted shortly after the March 2011 uprising against the Bashar al-Assad government, the Western news media adopted the same model that they had institutionalized during their reporting on Libya. The news media narrative on Syria drew heavily from second-hand evidence provided by official Western as well as Syrian opposition sources. News media propaganda emphasized the culpability of the Syrian government almost like a monolith. The fact that Western states and their allies had provided significant aid to the opposition—policies that destabilized Syria and further fueled the conflict—was ignored.

On 21 April 2012, the United Nations had tasked a 90-day monitoring mission in Syria to broker a ceasefire between Syrian government and opposition forces as well as to implement a six-point peace plan to end the conflict, put forward by the then-Special Envoy to Syria, Kofi Annan. Following its implementation, the peace plan had led to an initial decrease in violence. On 25 May 2012, about 116 civilians were slaughtered in the Syrian village of Taldou, which is located in the Houla region in western Homs. The so-called Houla massacre rekindled the conflict and this led to a suspension of the UN peace plan in August 2012. Moreover, Houla constituted the first major event that shifted international attention towards “humanitarian intervention” in Syria.

Two competing political narratives about the Houla incident should emerge: (1) According to Western officials and Syrian opposition activists, the Assad regime and its paramilitary forces—the Alawite Shabiha militias—had conducted a sectarian killing of Sunni Muslim civilians. (2) The Syrian government, on the other hand, had blamed opposition militants for the killings. The news media highlighted the first narrative whilst marginalizing the perspective of the Syrian government and its allies. This was striking since even about three weeks after the Houla massacre took place, Major General Robert Mood, then-Head of the United Nations Supervision Mission in Syria, said the facts and circumstances relating to the incident remained unclear and pointing to conflicting local witness testimony.

Moreover, there were important contextual factors. As Patrick Cockburn stated in a report for the Independent on May 27, 2012, the Houla “massacre could mark a crucial stage in the war in Syria because it will energize the insurgents inside and outside the country” and will also “underline that the ceasefire arranged by the UN-Arab League envoy Kofi Annan is foundering.” Additionally, in another article published a day earlier, Cockburn discussed how the ceasefire related to the war parties and the Houla event:

The ceasefire was only sporadically implemented from the beginning. The government has always had more interest in its successful implementation, which would stabilise its authority, than the insurgents, who need to keep the pot of rebellion boiling. The UN monitoring team says that during the ceasefire “the levels of offensive military operations by the government significantly decreased” while there has been “an increase in militant attacks and targeted killings”. But any credit the Syrian government might be hoping for showing restraint will disappear if the latest atrocities are confirmed.

If Cockburn’s statements were accurate, then the Houla massacre could have destabilized the Syrian government’s prospects under the ceasefire. Furthermore, as observed by the UN monitoring team cited by Cockburn, not the Syrian government but factions of the opposition had actually increased their militant attacks, which included targeted killings. And the Houla incident was mainly comprised of targeted killings. These contextual factors could at least have cautioned the news media about assigning culpability for the Houla massacre to the Syrian government.

Yet, the news media prominently carried indignant statements by Western official and Syrian opposition actors who demanded international intervention against the Assad-government. This discourse included discussions about the implementation of military policies, such as the imposition of a no-fly zone, as well as various political measures ranging from regime change operations, sanctions and aid for the opposition to demands for independent investigations and the referral of Syria to the International Criminal Court (ICC).

Significantly, my study found that eleven major national US, UK and Germany newspapers published 262 items during the first two-weeks of coverage after Houla, of which 133 (50.7 per cent) included statements mentioning or discussing some form of military intervention in Syria. On the other hand, the news media was hardly able to interrogate critically the goals of the Syrian opposition—which already in November 2011 had asked for foreign intervention—and its Western and Arab state supporters.

The news media only rarely provided analysis that cast a negative light on the Syrian opposition. For instance, a critical op-ed comment by Patrick Seale in the Guardian on 27 May argued: “The strategy of the armed opposition is to seek to trigger a foreign armed intervention by staging lethal clashes and blaming the resulting carnage on the regime.” That the Houla massacre fit well into such a pattern was hardly a concern for the news media.

In conclusion, it would not be surprising if the hyper-militarist discourse featured in the news media was, in fact, detrimental to the goals of the UN peace plan and contributed towards escalating the conflict in Syria.