Thank you for joining me in celebration of Holy Abapsusfbad (A better, and progressively socialistic, U.S. farm bill Appreciation Day, of course.)

In solidarity,

Galtisalie, a/k/a Brother Francisco

Seriously folks, this is the third and final part in an introductory series on the need for a humane socialist U.S. agriculture policy. (Part 1; Part 2.) For over a year I have been plodding along in my spare time researching, thinking, and writing U.S. agriculture-related pieces from what I will call a progressively socialistic perspective. Along the way I have developed the firm conviction that the lack of a comprehensive practical focus on agricultural issues is a major problem for the U.S. left, politically and programmatically.

My solidarity work on agricultural issues is a labor of love which has been building up to tonight’s arguably fool’s errand of proposing “a better, and progressively socialistic, U.S. policy for agriculture in the U.S.” Time is of the essence, so I have done my best as a species being to provide a draft framework which interested persons can critique and improve. 2018 is time for passage of the next farm bill.

Who cares? Speaking for myself, I have farmers in my family, am a trained soil scientist, and worked for decades in environmental positions where I sometimes worked on agricultural issues. My current job is ostensibly unrelated. I say ostensibly because it is impossible to work as I do with desperately poor people without having a recognized or unrecognized interest in the farm bill.

To many on the left, particularly those living in urban areas, the farm bill is never on the radar screen or perhaps something that happens every once in a while that is either irrelevant to solidarity work or simply a major example of corporate evil personified. I think an uninformed or apathetic view is a huge mistake. We should get over our disinterest and resignation.

We should make the farm bill a focal point of resistance and articulation of why democratic socialism, where the economy is democratically controlled by the people, is better than capitalism, where the economy is undemocratically controlled by one ruling coalition or another of capitalists.

Good humans interested in or dissatisfied with U.S. farm policy—and that should include everyone who believes in the struggles for class, gender, and racial equality—need to get into the political-economic details and also not miss the exploitative capitalist forest for the trees. We cannot effectively fight for justice in the city if we don’t really know or care what justice would look like for those living outside the city—or even the basics of what is in the current farm bill, which includes none other than the Supplemental Nutrient Assistance Program (SNAP).

SNAP will be at the center of upcoming farm bill debates. (www.capitalpress.com/…) Even though SNAP is authorized under the Food and Nutrition Act of 2008, as amended in 2014, under Sec. 4(a) it is always “[s]ubject to the availability of funds appropriated under section 18 of this Act ….” (fns-prod.azureedge.net/…) Russia was treated a lot better in the Trumpian 2016 Republican Platform (www.npr.org/…) than the food insecure. The platform directly advocated splitting SNAP from the farm bill, the better to gut the former:

Breaking the SNAP program—commonly known as the food stamp program—from the USDA could rewrite the playbook on how the farm bill is negotiated in Congress. For years, the farm bill has moved through Congress with the help of a fragile understanding that Democrats backing nutrition assistance and Republicans backing funding for farm programs would both get most of the money they sought.

An independent SNAP program could upend that arrangement, leaving the program more open to funding cuts. (“Republicans Target SNAP, Labeling Rules in Platform“

The left needs to be democratically holistic and united on at least some basic farm bill principles. Farm policy is complicated. Not every good human will understand, much less agree on, all of the details. But without a democratic groundswell Congress will perpetually be led by one coalition or another of the ruling class, not the working class, when it comes to food policy.

We are not so naive as to expect success this farm bill in obtaining passage of a holistic democratic socialist agenda or even a mildly progressive one. It will be a pitched battle this Congress to get anything good accomplished at all. Congress is not made up of 535 Bernie Sanders’s, a democratic socialist U.S. senator who deeply cares not only about society in general but also about small and medium-sized family farmers in particular, who are going out of business in his state and others every day. Should we remain complacent about these farmers’ plights? If we look carefully, we may find that we share many interests with them that can be advanced by a better farm bill. The so-called Freedom Caucus does make rank-and-file conservative Republicans from farm states somewhat dependent upon urban Democrats who are protective of SNAP and other progressive elements. But we know in advance currently relatively good elements will be seriously threatened and things will probably not turn out like we want on much of this farm bill.

That does not mean we cannot have our heads on straight on the overall farm bill and boldly begin to articulate a comprehensive people’s vision of the farm bill in contrast to the somewhat varying visions of the ruling class. Moreover, it is not enough to be upset about this or that component, such as environmental or public health impacts, and not care how it fits into the whole. It is certainly not enough to be focused on the negative, or to be grandiose and simplistic on the ease of devising, much less implementing, solutions. As responsible small “d” democrats, many of us also affiliated for pragmatic reasons as large “D” Democrats, we must always insist on our right and duty to stand up and be counted on the true side of liberty and justice for all, whether in the city or in the countryside.

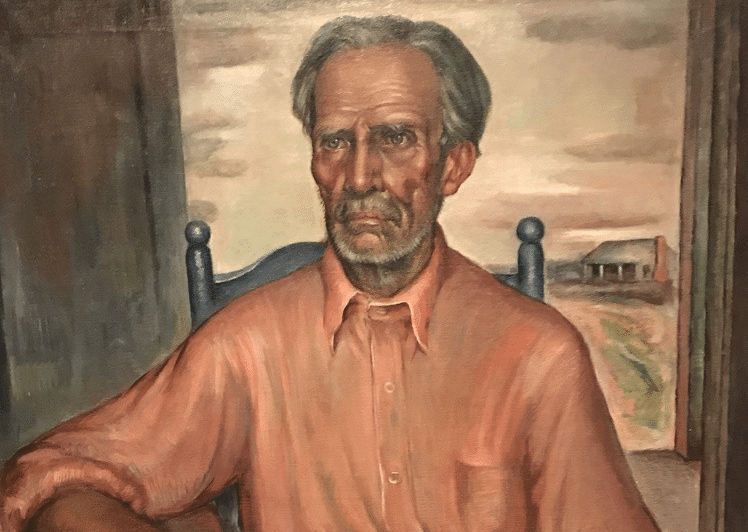

There was a time when, at great personal sacrifice and peril, Oklahoma Socialist Party farmers, in part building on the crushed foundation of the democratic Populist movement, almost built a successful mass movement in their state (www.dailykos.com/…). They creatively and flexibly borrowed theory from Jefferson, Jesus, and Marx.

They also paid keen attention to the facts on the ground as they understood them as struggling smallholder and tenant farmers desperate to feed their families. They threatened the ruling class of their state both with passage of fundamental political reforms and with grassroots advocacy of a practical partly cooperative and partly political program of agrarian justice. In the end, with World War I repression of socialist dissent as a backdrop, they were cruelly and crookedly defeated. The same may happen to us, but we must be forward-looking and steadfast.

Their work was powerful and should be celebrated first and foremost not for the particulars, relevant as some of them are (such as their dynamic harmonization of concern for social control of the means of production with acceptance of family farms in the Jeffersonian tradition) but because it was validating and authentic to their own real world experiences. We are not living in the past. We now recognize a more comprehensive set of problems than a century ago, particularly relating to conservation, environmental, and public health issues. But solving these serious issues cannot be done in isolation. It cannot leave out the difficulties of the workers in the fields and in the factory farms. To those who are struggling to make ends meet, socialism cannot be about waiting or even striving for a utopian tomorrow. It must be about honestly recognizing real human needs today and devising real solutions that also take into account the paramount need for system change to deep democracy with political-economic solidarity.

After passage of the current farm bill, Fred Magdoff, a leading U.S. agricultural expert who happens to be a compassionate independent socialist, observed:

Can Capitalist Agriculture be Improved Environmentally and Socially?

Of course! There are many things that have been done and more that can and should be accomplished in the future to deal with the ecological and social problems (irrationalities) created by capitalist agriculture. Some of these do not sufficiently threaten powerful interests that might be harmed, or the influential interests understand that, because of publicity, something must be done differently. In some instances something might be accomplished.

But what exactly would a rational agriculture be like? I propose this definition: A rational agriculture would be carried out by individual farmers or farmer associations (cooperatives) and have as its purpose to supply the entire population with a sufficient quantity, quality, and variety of food while managing farms and fields in ways that are humane to animals and work in harmony with the ecosystem. There would be no exploitation of labor—anyone working on the farm would be like all the others, a farmer. If an individual farmer working alone needed help, then there might be a transition to a multi-person farm. The actual production of food on the land would be accomplished by working with and guiding agricultural ecosystems (instead of dominating them) in order to build the strengths of unmanaged natural systems into the farms and their surroundings.

To develop this type of agriculture will require building it within a new socioeconomic system—based on meeting the needs of the people (which include a healthy and thriving environment) instead of accumulation of profits.

Hopefully the below framework provides an example of how we might begin to holistically interweave this paramount need to build a new truly democratic socioeconomic system with enough policy details to make practical strides forward from both political advocacy and direct action perspectives. One will readily note that much of this framework is not in a traditional farm bill. It would be radically transforming and some of it is downright radical but equally needed.

To better understand the framework of the current farm bill and farm bill history, one might watch this and other related videos by Johns Hopkins University:

Members of the working class in all locales and occupations share many of the same basic needs. It is simply not factually correct to expect farmers or ranchers, any more than food servers, janitors, or any others, to do without decent employment and health care. In these and many other ways, solidarity with agricultural workers is solidarity with all of the working class.

A Framework

- Democratization of farming and ranching operations and of supporting infrastructure: (a) enhance support for worker-controlled cooperatives and responsible small and medium-size family farms, ranches, and mixed crop-livestock farms; (b) stop subsidizing agricultural investment properties, large and very large farms and ranches not run as worker-controlled cooperatives, factory farm integrators, and poultry processing/meatpacking companies; (c) make public university-managed extension programs, with guidance from USDA and other federal agencies, the centers of regionally-appropriate sustainable research, development, and farmer, rancher, input management, and nutrient recycling assistance; (d) enhance existing seed banks and other tangible and intangible agricultural property currently under public ownership; and (e) democratically transition to public ownership, and in the interim strictly regulate in the public interest, other agricultural intellectual property not currently under public ownership, input production, factory farm integration, and poultry processing/meatpacking (with appropriate exceptions for operations addressing religious dietary preferences), and vigorously protect and require decent living wages for agricultural, factory farm, and poultry processing/meatpacking employees.

- Solidarity between rural and urban residents: (a) as part of the right to decent employment for all who need jobs and are capable of working, ensure access to free educational and training programs and alternative decent employment for working age active or former farmers, ranchers, and agricultural, factory farm, and poultry processing/meatpacking employees who may need new jobs; (b) transition to food security cards for all (which could automatically deactivate above an agreed threshold, such as when one’s household is in the top 20% in household income), and in the interim make SNAP and other nutrition programs much more available, sufficient, and reliable for all who are food insecure; (c) make high quality national health care available to all, including farmers, ranchers, and agricultural, factory farm, and poultry processing/meatpacking employees; (d) where requested, assist retiring farmers and ranchers in transferring their farms and ranches to new or returning farmers and ranchers or cooperatives and assist in developing alternative use plans or crop/livestock distribution arrangements for farms currently dependent upon single or double crop rotation or corn-based ethanol, food additive, factory farm integration, or processed food production; and (e) enhance sustainability and environmentally conscious nutrient recycling through supporting local production and appropriate, safe on-site composting.

Brief Discussion

In future pieces I will address details of the above framework. In the meantime, I mainly want to point out that this framework is partly inspired by four complementary sources. The first two are socialist, but the latter two definitely are not socialist although they have a focus on cooperation and protection of small and medium-sized family farms. Obviously effecting positive change in a farm bill cannot be merely about solidarity with other leftists and single issue groups.

First and second, respectively, are the Oklahoma Socialist Party’s flexible, pragmatic experience of the early 20th century, referenced above, and “Prout” socialism’s (www.dailykos.com/…) emphasis on progressive utilization of socialism with agricultural approaches that do not disrupt needed productivity but that do promote true cooperation and regional sufficiency:

The cooperatives envisioned by Prout are radically different from the state-run communes of the former Soviet Union, China and other communist countries which have, for the most part, been a failure. In these communes, very low rates of production often resulted in drastic food shortages. By denying private ownership and incentives, they failed to create a sense of worker involvement. Central authorities issued plans and quotas, and the local people had no say over their work. Coercion, and sometimes violence, was used to implement the commune system.

Prout does not advocate the seizing of agricultural land or forcing farmers to join cooperatives. Traditional farmers have an intensely strong attachment to the land that has been held by their ancestors–some would rather die than lose it.

After carefully evaluating what the minimum size of economic land holdings in a particular area should be, small farmers with insufficient or deficient properties (uneconomic holdings) would be encouraged to join cooperatives, while still retaining ownership of their land. (Maheshvarananda, Dada, 2012. After Capitalism: Economic Democracy in Action, Chapter 6.)

The third source is the mainstream National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition’s Agenda for the 2018 Farm Bill.(sustainableagriculture.net/…). This coalition represents the perspective of small, and even very small producers, many of them organic or growing crops that are not supported under the current farm bill. Its work is generally excellent. Its assessment and confrontation of the detrimental effects on small and medium-sized farms of subsidies to large and very large farms is spot on.

The fourth source is the mainstream heir to the farming perspectives of the democratic Populist movement, the National Farmers Union. (farmbill.org)

It is the second largest farmers’ organization in the U.S. and represents the views of small and medium-sized farms. In some places it represents the primary farmers’ group. Out of desperation to protect these farmers it sometimes is unable or unwilling to take on large and very large farms. This is analogous to the plight of many poverty groups, which must preserve SNAP at all costs.

To force the day of reckoning by hegemonic large and very large farms and undemocratic infrastructure interests will require a new and expanded coalition of progressive rural and urban residents that has never before existed in the U.S. Forming such a coalition could revolutionize American politics.

The other thing that I will point out at this time is that a transition to public ownership of input production, factory farm integration, and poultry processing/meatpacking is radical but demonstrably necessary. As Professor Magdoff and others have described, these industries are egregiously exploitative. The input manufacturers take advantage of farmers with products that render the farmers completely dependent and vulnerable. Meanwhile, contract factory farms generally are unable to do other than race to the bottom to stay in business. Finally, conditions for wage employees in many factory farms and in poultry processing and meatpacking facilities are brutal and inhumane. Not just the livestock being grown and slaughtered needs decent treatment. Regulatory control and redress of these conditions has been shown for over a century to not be obtainable under capitalism. Democracy is needed and inconsistent with private ownership under these conditions.