When Bolivia’s Constitutional Court made the decision in January to modify aspects of the Constitution that placed limits on the number of times an elected official could seek re-election, it sparked a flurry of negative coverage in mainstream media.

“Bolivia Tells President His Time Is Up. He Isn’t Listening,” a New York Times headline read. “President Evo Morales of Bolivia seems obsessed with staying in power,” another declared. Other mainstream publications have followed suit, with phrases such as “president for life” adorning the headlines and pages of The Washington Post and Bloomberg.

Nicolas Melendres, a Bolivian journalist and activist with La Resistencia, an alternative media platform, believes such statements by media are hypocritical. He told MintPress:

This is something that is not only done in Bolivia… we have the example of Angela Merkel in Germany. I believe it is already going to be her fourth term re-elected as Chancellor. And it’s okay, because she is democratically re-elected. There are other examples, if I’m not mistaken; they have the same electoral system in Spain. Spain does not have term limits…

And so why is it that they try to make us believe here in Latin America that re-election is bad? That continuity in governance is bad?

While corporate media cries “dictator,” Morales’ supporters ask why it is that Bolivia’s most popular president, under whose leadership poverty and unemployment have decreased dramatically—a fact that even the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has had to admit—cannot enjoy the same privilege of indefinite re-election as do many First-World leaders.

Melendres argues that opposition to Morales’ candidacy in 2019’s elections does not lie in any true concern for “democracy,” but rather in the threat Morales’ government has represented for Bolivia’s landed oligarchy and its associated foreign interests:

President Evo Morales has captured the aspirations of the majority of Bolivians, and made them reality… Naturally, the opposition is scared that they won’t win the elections in 2019 up against Evo Morales. And when we speak of the opposition, we are not only talking about the Bolivian opposition, but also foreign interests for whom Evo Morales represents a threat… Basically, Evo Morales represents a threat to global capitalism. He represents a threat to many capitalist interests in the world, and so it is natural that they try to bring him down.

The “Cartel of Lies”

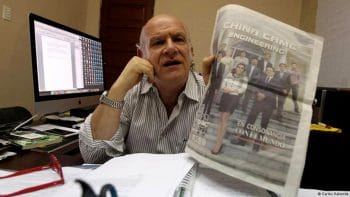

Carlos Valverde, the journalist who broke the story of Evo Morales’ alleged secret son with a teenage partner, would later admit his information was wrong, but not after the damage to Morales’ was already done. (Photo: Archivo)

The Bolivian right-wing, along with its North American allies and media, claim that the court’s decision on re-election is fundamentally anti-democratic, and that it is contradicting a referendum held on February 29, 2016 asking whether or not Bolivians wanted to amend the constitutional article imposing presidential term limits.

The vote was closely split, with the “no” securing barely 51 percent of the electorate for a surprise victory. The results of this vote are cited as evidence that “Bolivia said no” by much of the opposition and media like The New York Times, but Melendres argues that this is an oversimplification and generalization of what actually happened:

What is the discourse the opposition is using in respect to this?… That “Bolivia said no.”… The first idea that must be clear is that Bolivia did not “say no.” Fifty percent of Bolivia, or rather 50 percent of the electorate, said no. This is not “Bolivia.” The other 50 percent said yes.

In the months leading up to the vote, polls showed a polarized Bolivia, but with the “yes” vote holding a small but consistent lead.

However, in the days leading up to the vote, a media scandal consumed Bolivia’s press when journalist Carlos Valverde broke a story that Morales supposedly had fathered a secret son with a teenage partner, Gabriela Zapata, and covered it up. The story was later revealed to be “fake news,” but the damage was done. The supposed “scandal,” along with other stories claiming that Vice President Alvaro Garcia Linera had lied about his education, was enough to tip the vote, just barely, in favor of the “no” vote.

In the months following the referendum, Morales’ government denounced a group of the country’s most powerful journalists as a “cartel of lies,” fabricating sensationalist stories to manipulate public opinion during key electoral moments.

Media lies, a transnational venture

Himself a journalist on the front-lines of Bolivia’s media battle, La Resistencia’s Melendres told MintPress that in political processes like Bolivia’s, capitalist media can often be a determining factor:

The media, when all is said and done, can decide whether a government enters or not… It is deception, lying, that can confuse the people … The media can’t be unlinked from the ones who finance it … The media is always financed by a certain social class that has a determined interest. They want that the people hear only what this social class has in its own interest. The majority of the media outlets in the world are capitalist enterprises that naturally exercise global capitalism and imperialism as hegemony over public opinion.

Indeed, Bolivia’s “cartel of lies” reveals a national media landscape intimately tied to foreign, imperialist interests.

One of the most prominent members of the “cartel,” Raul Peñaranda, is the founder of Pagina Siete, one of Bolivia’s most prominent papers, and currently is managing editor of the Agencia Noticias de Fides.

Raul Peñaranda speaks at a National Endowment for Democracy sponsored event in Washington D.C., June, 2017. (Photo: Susana Escobar/Twitter)

Peñaranda, however, is closely tied to the U.S. Department of State-funded National Endowment for Democracy (NED), where he currently holds a fellowship. His NED biography bills him as an “independent” journalist, who is fighting against “mechanisms used by the Bolivian government to infringe on democratic liberties and to control and co-opt independent media outlets.”

Rather than denying his activities in concert with the U.S. Department of State, Peñaranda has published articles on NED-associated websites bragging about his role in affecting the outcome of 2016’s referendum.

Peñaranda’s successor at Pagina Siete is Juan Carlos Salazar, who was also appointed as the director of the Bolivian NGO, Foundation for Journalism, in 2016. The Foundation for Journalism claims to be “a non-profit organization that was founded by Bolivian journalists,” which “does not have ideological, political, racial or religious commitments.”

The supposedly “independent” Foundation for Journalism is, however, afforded a spot on the list of organizations funded by the NED.

The NGO-media complex

Demonstrators march along the Santa Fe road towards Santa Cruz, Bolivia, Tuesday, Sept. 16, 2008. Tens of thousands of supporters of Bolivia’s President Evo Morales marched towards the opposition stronghold of Santa Cruz de la Sierra, to demand the imprisonment of Pando’s province Gov. Leopoldo Fernandez and the return of state buildings seized last week by opponents to Morales’ government during violent protests that ended up with several people dead.(AP Photo/Dado Galdieri)

Evo Morales’ Movement Toward Socialism began to surge in popularity and influence in 2004 as an alliance of campesino coca farmers with leftists and marxists. This alliance is embodied in the duo of Morales, a cocalero, and Vice President Alvaro Garcia Linera, who was a former leftist guerrilla member on the U.S. terrorist list.

Argentine journalist Stella Calloni argues in her book, Evo en la Mira: CIA y DEA en Bolivia, that the United States has engaged in “low intensity war” tactics to undermine Morales’ leadership and set the stage for possible regime change. She argues that this became clear during an attempted coup of September 2008, when it was discovered that U.S. Ambassador Philip Goldberg had been working with separatist groups in several regions of the country. He was expelled as ambassador that same year. According to Calloni:

They tried to depict a ‘popular rebellion’ against Evo Morales, which was in reality an action of low intensity warfare, that had, as it is now known, the support of mercenary groups within and outside the country; and special troops of the United States in Paraguay, in the border zone with Bolivia, to ‘enter’ as soon as the coup happened ‘to help the Bolivian people’ in their struggle against the supposed ‘dictator.’

Furthermore, the plan was to separate the wealthiest region of the country, called the ‘Media Luna’ zone (Santa Cruz, Beni, Pando), where the greater part of the Amazon and Tarija region extends. This is an old dream of the oligarchs of this region, brutally racist and separatist, who furthermore covered up Nazis such as the ‘butcher of Lyon,’ Klaus Barbie, and other Nazis who arrived from Croatia, that together with ex-military officers of the Argentine dictatorship form the elite oligarchy of Santa Cruz.

The conflict with right-wing separatists reached its climax on September 11, 2008, when at least 13 Indigenous supporters of Morales were killed in the Pando region, prompting the government to declare the region under a state of siege and bringing in the military to control the area. An emergency UNASUR session called by Chilean president Michelle Bachelet declared “full and decided support for the constitutional government of President Evo Morales.”

The Media Luna region has continued being a center of conflict for the Morales government, and of efforts to undermine its image, mostly in the form of the controversy surrounding plans to construct a highway through the Isiboro Secure National Park and Indigenous Territory, commonly known as TIPNIS, to connect the Beni department with Cochabamba.

A consultation was held in 2013 with the Indigenous communities of the region, in which the majority supported the project. However the highway has been strongly opposed by various environmental NGOs and foreign media, which have broadcasted the controversy to an international stage. Much of this began when AVAAZ, an advocacy group that has been known to promote war in Syria, launched an online petition asking recipients to demand the Bolivian government cease the project.

While La Resistencia’s Melendres emphasizes that the debate over TIPNIS and how best to minimize environmental impact is important and ongoing in Bolivia, he offers a scathing critique of foreign environmentalists coming into the country:

What are the most polluting countries in the world? They are the “post industrial” countries … all of the First World … And naturally, what do these countries do? What they do is, instead of reduce their environmental pollution, they give funds to NGOs in Third-World countries, so that these NGOs go and tell the governments of those countries that they don’t develop themselves … In Bolivia, we are not going to serve environmentalists from First-World countries. We need to develop ourselves. We need to transform nature, so that there are not children who go to sleep hungry and with empty stomachs.

Indeed, the regions within and around TIPNIS are among the most isolated and poor of Bolivia, with little access to basic services, such as health centers or hospitals. Although concerns about environmental damage are real, supporters say the highway has the potential to lift people out of a situation of extreme poverty.

The Beni region is also the country’s major meat producing region; however, its isolation has made it difficult for producers to engage in trade.

Melendres explained to MintPress that Beni’s inability to directly bring its product to market has kept the area in poverty, dependent on ranchers acting as middlemen to transport the product by plane to Santa Cruz, where it is then resold and exported to the rest of the country. “And so, we are speaking of … a type of profiting bourgeoisie, or a social class in Santa Cruz of these ranchers that have a monopoly,” Melendez said.

These material interests in defense of a lucrative monopoly add greater nuance to the TIPNIS matter than the overly simplistic image that some environmentalist groups portray.

The TIPNIS conflict has been a symbolic struggle for Bolivia. It embodies the genuine difficulties that come with leading and transforming a historically colonized country, and the contradictions of developing a country mired in poverty while also caring for the environment.

Unfortunately, it has also demonstrated all too well the insidious ways in which media and organizations connected to both foreign and local interests can exploit internal tensions. Rather than seeking to understand the nuanced facets of an internal problem, an exaggerated version is broadcast to the world, of an Indigenous leader-turned-president trying to destroy the Amazon and the communities who live there.

Can Bolivia avoid regime change?

Before Morales had even arrived to office, U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice expressed in 2005 that the United States was “very concerned” about a “party of coca cultivators” that was surging in popularity. “Something curious” was happening in Bolivia, she said.

Morales, all too aware of the magnitude and complexity of his project, has not been shy about taking measures to curb activity against his leadership. Among the first measures taken was requiring all U.S. citizens to obtain a visa to enter the country.

In 2013, Morales expelled the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), claiming that it was attempting to foment opposition by funding and backing various NGOs and separatist groups.

Supporters of Bolivia’s President Evo Morales attend a rally in favor of his reelection, in La Paz, Bolivia, Wednesday, Feb. 21, 2018. Supporters of Morales marched in the 2 year anniversary of the referendum that rejected his bid for another reelection. Bolivia’s Constitutional Court is allowing him to go forward with his run to a fourth mandate. (AP Photo/Juan Karita)

When U.S. Ambassador Philip Goldberg was expelled in 2008, the measure enjoyed wide support among a country that is known for its anti-imperialist sentiments. Morales embodies this popular sentiment, and has not softened his rhetoric toward the United States with time, as some perhaps hoped he would. An active social media user, Morales frequently takes to Twitter, condemning U.S. interference around the world.

To one who pays attention to sessions in the United Nations Security Council, the small Andean country’s large presence in international relations would be obvious. Bolivian Ambassador, and close friend to Morales, Sacha Llorenti, has been known to show up to sessions on Palestine wearing a Keffiyeh.

In April, 2017, when several Western governments held up photos of supposed “evidence” that the Syrian government had used chemical weapons, Llorenti came prepared with his own photos, of former U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell holding the infamous vial of “anthrax” he used to make the case for war in Iraq. “I believe it’s vital for us to remember what history teaches us,” Llorenti told the council.

But while Bolivia enjoys more success domestically and makes its presence known internationally, the stakes have continued to grow, as Morales finds himself representing one of the last strongholds of the 21st century’s surge of South American leftism. With soft coups having taken down leftist governments in Brazil, Argentina, and Ecuador, a new right-wing administration in Chile, and an ongoing economic war crippling Venezuela, the geopolitical situation is far different from what it was when Evo came to power riding the Bolivarian wave.

Former Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa assessed the situation for the Latin American left in a recent opinion piece for Granma, concluding that media is currently acting as the primary destabilizing instrument of regime change:

The problem is much more complex if we consider the hegemonic culture constructed by the media — in the Gramscian sense, that is — assuring that the wishes of the great majorities are in line with the interests of the elites. Our democracies should be called media democracies instead. The media is now a more important component of the political process than parties and electoral systems. It has become the true representative of conservative and business political power.”

It is perhaps unsurprising then that Evo Morales — who concluded his 2005 inauguration speech with a cry of “death to the Yankees!” — is targeted by media. As he situates himself for re-election, one should have no doubt that such efforts toward destabilization and misinformation will only continue growing.