Colombia’s formal partnership with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) marks the first time that a Latin American country has joined the European group, and signals a new shift toward the Global South by the Cold War-era alliance.

Colombia’s entry into NATO as a “global partner” signals that the U.S. military top brass are likely to call the shots for the South American country both in terms of its security policies and its geopolitical orientation, which becomes all the more crucial as the North Atlantic alliance increasingly strives to become a power in the South Pacific amid rising friction between the U.S. and China.

NATO began its partnership agreement with the South American nation in May 2017, immediately following the peace deal between Bogota and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC-EP), yet the country still continues to be plagued by right-wing paramilitary activity, security forces who act with impunity, and the dire inequality that originally birthed groups such as FARC-EP.

So-called “global partners” of NATO are largely those countries that lie firmly in the Anglo-American imperialist sphere of influence or were directly occupied by the U.S., including Afghanistan, Australia, Iraq, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Mongolia, New Zealand and Pakistan.

The 29-nation alliance was formed in 1949 at the dawn of the Cold War for the purpose of consolidating a strategic bulwark against the spread of communism and Soviet hegemony in the Euro-Atlantic region.

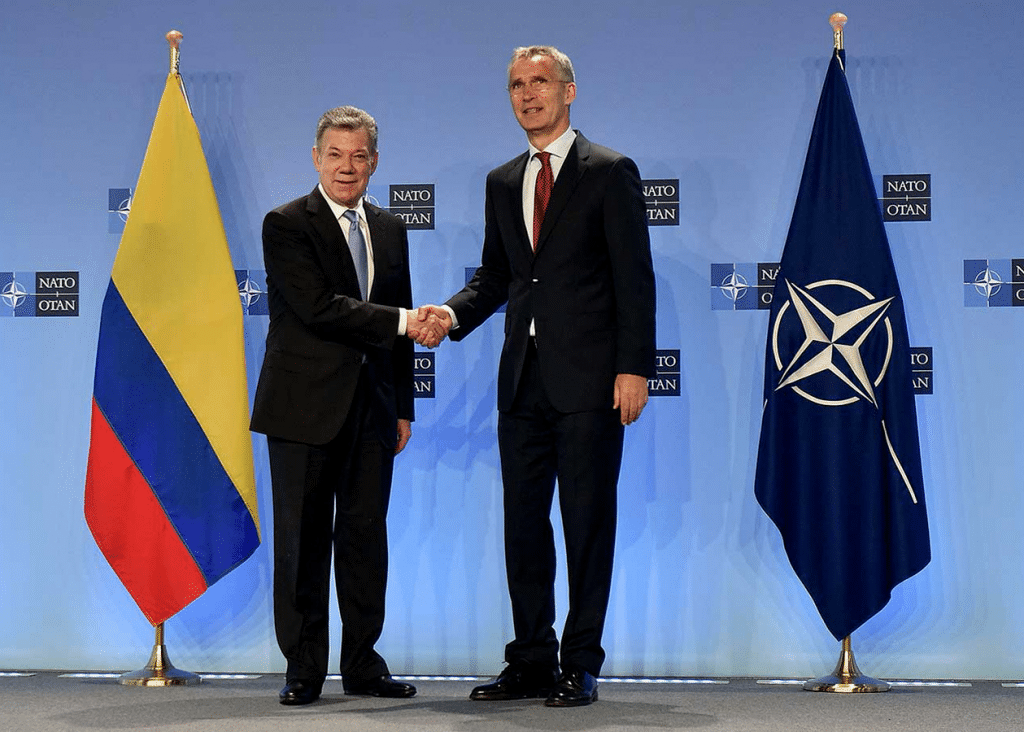

Speaking in a televised address, Nobel Peace Prize laureate and outgoing Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos addressed his country’s membership in the military alliance:

Colombia benefits a lot from being an active part of the international community, many of the problems we face are increasingly global and need the support and collaboration of other countries for their solution.

According to NATO, the new partnership will focus on cybersecurity, maritime security, and anti-terror and organized crime operations. The partnership will also include programs relating to the standardization of military practices, joint training and military exercises, and the modernization of the Colombian Armed Forces along NATO lines.

Colombia’s Integration Into U.S.-ruled Security Architecture Long in the Making

While the news came as a surprise to some, Colombia and the North Atlantic alliance have long collaborated in these fields. The process is the culmination of right-wing President Alvaro Uribe’s opening-up of the country to the United States during the bloody “Plan Colombia” campaign versus FARC-EP, which saw the U.S. provide military aid to the country. By 2009, Uribe fast-tracked an agreement granting the U.S. military the use of two maritime bases, three air force bases, and two army bases in the country.

Under Uribe’s successor, Santos, the Colombian Ministry of Defense signed the first security and cooperation agreement with NATO in 2013, provoking an outcry from progressive governments in the region including Venezuela, Nicaragua, Bolivia, Brazil and Ecuador.

Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos, flanked by SOUTHCOM admirals, arrives at SOUTHCOM’s Colombia military headquarters. Jose Ruiz | DoD

Bolivian President Evo Morales denounced the move as a “provocation” and conspiracy against the “anti-imperialist Bolivarian countries” in the hemisphere, noting that the agreement came shortly after Santos had met with Venezuelan coup-supporter Henrique Capriles.

Morales noted:

How is it possible that Colombia wants to be a member of NATO? What for? To have NATO commit aggression against Latin America, so they can invade us, as they have done in Europe, Africa and Asia?

On Thursday, RT aired an interview by former Ecuadorean President Rafael Correa of Santos, where the ex-president asked why Santos, a Nobel laureate, would ever want to join NATO.

The Colombian president noted that bringing NATO operations to Latin America was out of the question, and the “global partner” status was largely one of assimilatng “best practices” in terms of military purchases and training, while even participating in military “peace missions elsewhere in the world” without obligating Colombia to take part in military operations it chooses not to join.

The North Atlantic Alliance Goes to the South Pacific?

While past moves signaling Colombia’s integration into the U.S.-dominated Atlantic security architecture were greeted by a storm of denunciations from Latin American leaders, this time only Venezuela’s Ministry of Foreign affairs slammed the,

the intention of the Colombian authorities… to introduce a foreign military alliance with nuclear capability to Latin America and the Caribbean, which clearly constitutes a serious threat to regional peace and stability.

Bolivia, in the meantime, finds itself diplomatically helpless as it struggles to regain leadership over the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR), which increasingly finds itself to be a relic of the bygone so-called “pink tide” era, especially after the pro-U.S. governments of Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Peru and Paraguay quit the group in protest of Bolivia’s assumption of its pro-tempore presidency.

Yet Santos himself has stated that he is against any military intervention by the U.S. against Venezuela, noting:

That is not the solution–a Marine invasion of Venezuela would be catastrophic and would also spawn sequels effecting several generations. A U.S. military intervention would be a catastrophe for Venezuela and for Latin America’s relations with the United States.

Yet some analysts fear that Bogota will adopt a more confrontational stance against Caracas if former president Uribe’s right-wing protégé, Ivan Duque, wins the upcoming Colombian elections.

While NATO was conceived to protect Europe from alleged “Soviet expansionism” following World War II, the post-Soviet era entailed Russia’s near-complete encirclement of Russia by U.S./NATO military infrastructure and forward operating bases in Europe.

Faced with questions about the continued relevance of the North Atlantic alliance, NATO has sought justification for its existence from Central Asia to Sub-Saharan Africa and has even floated the idea of indirect intervention in the South China Sea dispute.

However, China’s presence extends from the Eurasian landmass to the Southern Cone, raising the importance of the Pacific Ocean in the strategic calculations of U.S. imperialism and its junior partners from Europe to the Andes.

By expanding its “global partners” list to encompass Colombia, Washington is clearly moving to regain hegemony over South America with the consent of elected governments across the continent, ranging from Santos in Colombia to Mauricio Macri in Argentina, Michel Temer in Brazil, and even Lenin Moreno of Ecuador.