I have long argued (e.g., here, here, and here) that capitalism involves a kind of pact with the devil: control over the surplus is reluctantly given over to the boards of directors of corporations in return for certain promises, such as just deserts, economic stability, and wage increases for workers.

In recent years, as so often in the past, we’ve witnessed those at the top sabotaging the pact (simply because they have the means and interest to do so) and now, once again, they’ve undermined their legitimacy to run things.

First, they broke their promise of just deserts, as the distribution of income has become increasingly (and, to describe it accurately, grotesquely) unequal and the tendency toward high concentrations of wealth has returned, threatening to create a new class of plutocratic coupon-clippers. Then, they ended the Great Moderation with speculative decisions that ushered in the worst economic crisis since the First Great Depression. And, now, the promise of using the surplus to create jobs that would raise workers’ pay appears to be falling prey to directing the surplus to other uses: share buybacks and increasing CEO salaries.

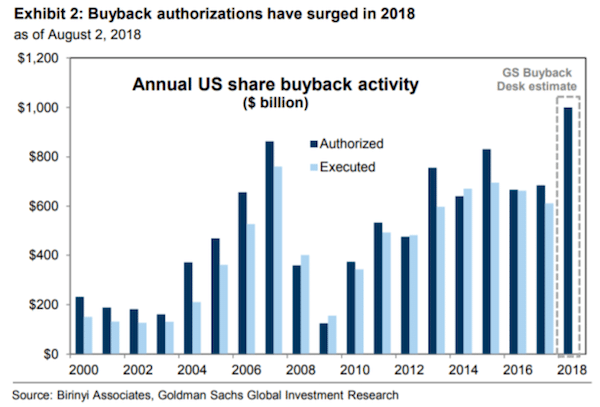

According to a recent report by Goldman Sachs, stock repurchases will reach $1 trillion this year, up 46 percent from 2017 on the back of tax reform and strong corporate profits. Corporations buying back their own stocks leads to higher stock prices, which is an additional benefit to those who own the stocks—on top of the dividends they regularly receive.

As I explained earlier this year, the top 1 percent owned in 2014 almost two thirds of the financial or business wealth, while the bottom 90 percent had only six percent. That represents an enormous change from the already-unequal situation in 1978, when the shares were much closer: 28.6 percent for the top 1 percent and 23.2 percent for the bottom 90 percent). So, rising stock prices are both a condition and consequence of the obscene levels of inequality that obtain in the United States today.

And who loses? Workers, of course. A recent report from the National Employment Law Project calculated that McDonald’s could have paid each of its 1.9 million workers $4 thousand more a year if it had used the $21 billion it spent between 2015 and 2017 on stock buybacks to reward its workers instead. Starbucks could have given each of its workers a $7-thousand raise. With the money currently spent on buybacks, Lowe’s, CVS, and Home Depot could give each of their workers pay increases of at least $18 thousand a year.

But they’re not. Instead, corporations are using their enormous profits to repurchase their own stocks and, in addition, rewarding their executives with enormous pay increases.

According to Bloomberg, the median CEO-to-worker-pay ratio last year was 127 to 1 (at International Flavors & Fragrances Inc.). For U.S. corporations, the ratio ran from 0 (for Twitter, because CEO and cofounder Jack Dorsey received $0 in 2017) to 4,987-to-1 (at Mattel, where CEO compensation was $31,275,289).*

As it turns out, some of the most extreme examples of the gap between executive and median worker pay occurs at companies directly supported by federal contracts and subsidies. The latest Executive Excess report, published annually by the Institute for Policy Studies, found that at many federally funded companies the gap is far in excess of what ordinary American taxpayers find acceptable. For example, more than two-thirds of the top 50 government contractors and top 50 recipients of federal subsidies, receiving a total of $167 billion, currently pay their chief executive officer more than 100 times their median worker pay. At the top of the scale are leading military contractors, with the top bosses at Lockheed Martin, Boeing, General Dynamics, Raytheon, and Northrop Grumman each earning an average of $21 million, or between 166 and 218 times average worker pay.**

So, do Americans have any sympathy for the devil? The typical American believes CEO pay should run no more than six times average worker pay, according to the “2016 Public Perception Survey on CEO Compensation” at Stanford Business School (which mirrors a similar study by Sorapop Kiatpongsan and Michael Norton). Clearly, given the obscene ratios of CEO to average worker pay, Americans are no longer puzzled by corporations’ game. My guess is we’d see the same results if someone conducted a survey about stock repurchases. U.S. publicly traded companies across all industries spent almost 60 percent of their profits on buybacks between 2015 and 2017, while workers’ wages stagnated.

Sure, the tiny group at the top may present themselves as people of wealth and taste. But they’ve also shown they can lay waste to the economy they alone control, and they are clearly in need of some restraint. So, now, almost a decade into the current lopsided recovery—as they watch with glee their growing profits and an increasing gap between those who receive the surplus and everyone else—they deserve no sympathy whatsoever.

They’ve broken the pact and now their game is up.

*But Dorsey still owns a bundle of equity in Twitter, whose stock has increased in value 20 percent since the beginning of 2018. As of April 2 Dorsey owned 18 million shares of Twitter, currently worth $627 million as of Tuesday’s closing price. Dorsey also is the CEO of payments company Square, in which he owns 65.5 million shares, which currently would be worth $6 billion.

**The Geo Group, one of the primary contractors for the notorious immigrant family detention centers, took in $663 million in Justice Department and Homeland Security contracts in 2017. Geo CEO George Zoley pocketed $9.6 million that year, 271 times more than his company’s median worker pay of $35,630.