Health care is a big and profitable business. As a Wall Street Journal article points out:

[The U.S.] will soon spend close to 20% of its GDP on health–significantly more than the percentage spent by major Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development nations…Health care has become a larger part of the economy, creating powerful constituencies resistant to changing the way the system operates.

The health-care industry overtook the retail sector as the nation’s largest employer in December, giving local economies and their workers a stake in the industry’s growth. Health jobs surpassed manufacturing jobs in 2008.

The revenues of health-care companies represented nearly 16% of the total revenues of firms in the S&P 500 last year, up from about 4% in 1984.

Health-care companies have more than doubled overall lobbying spending since 1998, and have become a bigger percentage of total lobbying by industries.

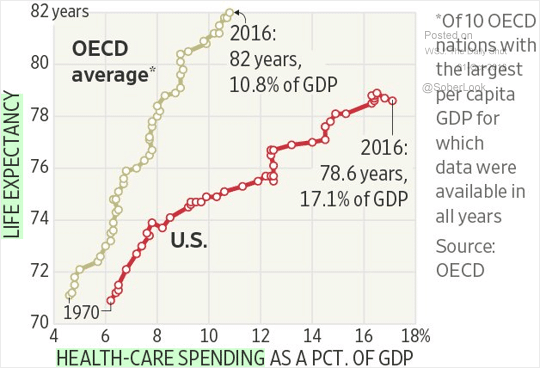

Unfortunately, as the Wall Street Journal article also goes on to say, “despite the higher spending, the U.S. fares worse than the OECD on most major measures of health.”

The following chart provides one illustration of the distorted nature of our health care system. As we can see, the U.S. spends a far higher share of its GDP on health care than the OECD average, yet has a significantly lower life expectancy.

The article highlights drug prices as one of the key drivers of U.S. health care costs, noting that they, “have risen the most of the three largest components of health spending since 2000, followed by hospital care and physician services.”

The power of the drug industry is immense, and their lobbyists actively work to ensure that the industry’s profits will remain healthy regardless of the social consequences. The text of the recently negotiated United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) makes this clear.

As a Washington Post story explains:

A handful of major industries scored big wins in President Trump’s North American trade agreement—at times at the expense of ordinary consumers in the United States, Canada and Mexico.

The winners include oil companies, technology firms and retailers, but chief among them are pharmaceutical companies, which gained guarantees against competition from cheaper generic drugs. . .

The pharmaceutical industry won stronger protection for sales of so-called biologic drugs, which are typically derived from living organisms and are administered by injection or infusion. The medicines are among the most costly and innovative on the market and are a major driver of drug spending.

USMCA guards new biologic drugs from cheaper generic competition for “at least ten years,” compared with current protection of eight years in Canada and five years in Mexico.

“By increasing the term to 10 years, there will be less competition and higher prices,” said Valeria Moy, an economics professor and the director of Mexico Como Vamos, a think tank in Mexico City.

Having more protection in that area means higher prices for consumers.

The agreement provides extra protection to drug companies in the much larger U.S. market, as well. Current U.S. law protects biologic drugs from generic competition for 12 years, but some Democrats, including in the Obama administration, have pushed to lower that to seven years as a way to speed cheaper generics to the market and lower drug spending.

Critics of the trade agreement argued that by setting a minimum of 10 years of protection, the trilateral pact shields the pharmaceutical industry from future legislative attempts in the United States to shorten biologic drug monopolies.

It “decreases U.S. sovereignty,” said Jeff Francer, general counsel for the Association for Accessible Medicines, a lobbying group for generic drugmakers.

It would be much harder for Congress to try to roll back 12 years to seven years if we’re enshrining 10 years in a free-trade agreement.

In short, our health care system operates very efficiently for the health care industry, and the industry appears well organized to keep it that way.