Born in 1938, Julio Escalona began his revolutionary activity at an early age in the MIR (Left Revolutionary Movement). Later he helped to found the urban guerrilla OR (Organization of Revolutionaries) and its political arm the Socialist League. A professor of economy in Venezuela’s Central University, he has also been part of Venezuela’s UN delegation. Today, while continuing to write and reflect, Escalona serves as member of Venezuela’s Constituent Assembly.

Recently you wrote an article about the resurgence of fascism in our continent, as embodied in Brazilian presidential candidate Jair Bolsonaro. You hypothesize that, if the economy continues its chaotic course and the pauperization of Venezuela’s masses goes forward, a fascist option could emerge in here. Can you tell us about this?

As long as the welfare state existed and relations of power evolved under it, fascist projects were impeded. There have always been fascist practices, that is to say violence, torture, violations of human rights, attacks on democracy, which generally are fascist practices…They’ve always been present in Venezuela but without being the usual political method. What’s been usual in Venezuela has been a combination of forms of struggle: there was an authoritarian government, which was maintained by concessions to people and workers and also buttressed by repression, in what was called “the war against insurgents.”

Today in global capitalism, finance capital has become hegemonic. Financial capital cannot coexist easily with democracy, because it liquidates the spaces of interclass negotiation, which was the social and political basis for representative democracy. Liquidating those spaces of negotiation means that there are two options: either a move toward fascism or a growing popular movement, which is what the Chavista period represented in Venezuela. The option that in fact emerged here was that of the popular movement and the practice of participative and protagonic democracy…

Moreover, our popular struggle relied on something Chavez developed, which was both the worldview and the practice of solidarity. Practicing solidarity developed because people could see the advantages of solidarity, but it led the Empire to realize that the way to defeat Chavismo would be to defeat the concrete practice of solidarity here: stimulating individualism and promoting egoist solutions.

To do that, imperialism worked to make Venezuelan society chaotic, destroying forms of organization and relations of solidarity. That is what has been happening in Venezuela: a process of destroying relations of solidarity along with a reawakening of individualism through what is here called bachaqueo(1), which is in essence the individual solution. Individual solutions of that kind are only possible by damaging the collective, which is precisely what capital tries to do.

So we have entered into a process in which individual solutions have not exactly won out, but they have been strengthened and the fabric of solidarity has begun to weaken. One thing goes hand-in-hand with the other: you weaken the social fabric and relations of solidarity, at the same time as you strengthen individualism. That’s what’s underway right now in Venezuela.

Fascist experiences tend to result from a frustration of the popular movement. The popular movement had begun to emerge in Germany. The communist party got to be very strong there. However, defeating the communists and the socialists in Germany led to fascism, because the liberal position and especially the neoliberal position is based on weakening the state, but above all in weakening the state as a representative of the population’s interests. At the same time, the state is strengthened as a vehicle of repression and persecution.

That’s how we get to a situation of a fascist kind, since [it amounts to] strengthened power that is located above society, which decides people’s rights and determining what is done and not done, while forcefully encouraging one to think about oneself. It tells you: it doesn’t matter if you kill, it doesn’t matter if you torture, it doesn’t matter if it’s a dictatorship. But you can work things out for yourself.

In Venezuela, the Right is trying to frustrate the Chavist process, because they know that frustrating it will lead to a reaction in the opposite direction. State power, which Chavismo used to respond to popular demands, could be used to repress. This would go hand-in-hand with a fascist demagogic discourse, showing how you can enrich yourself, you can live better. That discourse tells you: you shouldn’t be so stupid as to think about other people!

Faced with this, what is the government doing?

The government should confront this situation. It has the political and legal tools–all the necessary instrument to confront the Right’s main tactic today, which is permanently raising prices. The Right does this because it’s what most hurts the people. As a result you cannot buy a kilo of meat. Nobody can buy it! That’s the truth! Nor can you buy a kilo of chicken.

That’s to say the basic goods that people use can’t be bought, but neither can you get anything else. When they became aware that the people were eating vegetables, then they raised their prices. Wherever they see that the population is beginning to turn, the Right immediately hikes up prices to reduce people to a situation of defenselessness.

Salaries were raised significantly as a result of the measures taken by President Maduro, and when they became aware of this, what did they do? They raised prices to such a degree that salaries now don’t allow you to buy anything!

The government has to confront inflation, and it possesses the means to do so. It can establish a new relation between the Bolivar and the Petro and raise the real salary. Those are steps that can be taken. They are not easy of course, because [businessmen] will begin to hoard basic goods. However, the government also has the instruments to solve these problems…

On the subject of fascism, in 2017 we saw a fascist uprising. It was in the face of this fascist outbreak that President Maduro called for a National Constituent Assembly (ANC), which had two tasks. The first was to change the correlation of forces to end the fascist insurrection. That was successful. However, the ANC also was charged with writing a new constitution. Can you tell us how the ANC is working internally? Has there been a debate in commissions and is the new constitution being developed?

The idea that the government had in convoking the ANC was, as you said, to defeat street violence. The Venezuelan people understood this clearly and massively went out to vote for it.

But the question of violence was not properly understood. People have said: “peace triumphed.” However, what was defeated was street violence, so the opposition changed their form of struggle and began a battle on the economic front, which is where we have not been able to defeat them.

So, we defeated the street violence but not the economic war. One form of violence was ended, but other forms became stronger. It’s there that they have hit most hard. That’s the case because while the street violence jammed up the city and created chaos, it never had the people’s support.

For that reason, defeating street violence was easy. Maduro did what one does in that sort of situation: appeal to the people. Convoking the ANC was a way of mobilizing people, and that was correct. Nevertheless, where we have not been able to mobilize people is in the struggle against the economic war.

Winning that struggle would require making people conscious of the nature of the problem. It’s a question of awareness because the Chavista movement, the Bolivarian movement, has enough people to deal with the economic emergency. Yet it’s there that we have failed, in mobilizing people to confront the economic war.

Additionally, the government has not taken the steps to limit prices and keep basic goods from disappearing–in effect, all the things that make up the economic war. If it’s a war, that means it cannot be resolved only through dialogue. In a war, of course, there are spaces for dialogue, but only if you have both sides wanting to negotiate. But what in fact happened is one side wanted to dialogue and the other side pretended to want to do it, went to the table, approved things that they immediately broke, making the government appear ridiculous in front of the population.

The government says, “We agreed on such and such prices.” What’s more, the businessmen sign it and it comes out in the official bulletin, but they break the agreement immediately. Breaking the agreement has to be punished by the state! It hasn’t done so! For me, that is the most serious problem that we have now because it could cause the population to lose confidence in the government.

Up until now, the government has been strong because it has maintained people’s confidence. That is what was proven in recent elections. If that confidence is broken, then we might have a critical situation.

Fascist spaces now exist in Venezuela without having had either the opportunity nor the leadership to go forward. The internal Right [within the government] is working to open opportunities for fascism, while, from the outside, imperialism is working to find the leaders who can direct the movement. So I think the political struggle in Venezuela has to face the possibility that a fascist movement could emerge that would have a base in the country…That danger exists in Venezuela, and I think it is our most serious problem now.

What is happening with the National Constituent Assembly? Are the commissions meeting? Is there debate?

The National Constituent Assembly has been working and there is ample evidence of that. The commissions [workgroups by area, such as economy, gender, etc] are the ones that have most of the work for now, but those are closed-door spaces.

The problem, from my point of view, is that even though the ANC has approved open debates in the street, in the barrios, in rural areas, etc., that hasn’t happened. A void exists, and it has to be filled soon! The debate internally within the ANC cannot remain inside the four walls of the Assembly chambers. The leadership, the heads of commissions, the delegates…everybody must go out to debate in public squares, in the barrios.

I myself have been to open meetings, but initiatives like that have occurred as a personal project. They are not enough. According to Hermann Escarra, who heads up the Constitutional Commission, eighty percent of the constitution’s text is ready, but, where is the debate? The open debate? I assume that this problem will be solved. The truth is that nobody has to ask for permission to debate.

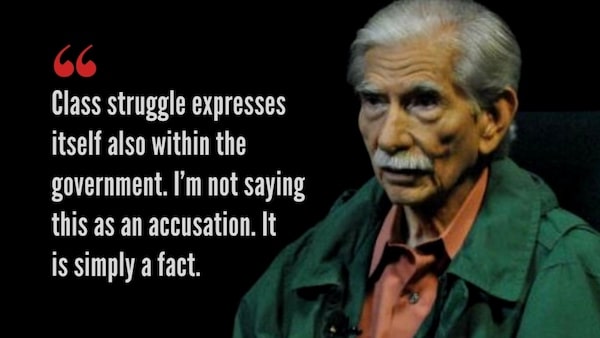

Now, what you should understand is that class struggle expresses itself in all societies and in all spaces of society. Thus, class struggle is also found within the government. I’m not making an accusation; it’s simply a fact. There is a very active class struggle in Venezuela, and it expresses itself within the government, within labor unions, and within all communities. It’s necessary to overcome the closed-door tendencies in this class struggle…

In recent months, popular Chavista movements have begun to question the government. They insist on being heard, and they want the government to rectify its errors. The best-known case is the Admirable Campesino March. Can you tell us about this new phenomenon–these rebellious movements that are emerging within Chavismo–and particularly about how Venezuela’s peasant movement might help to revitalize and rebuild the Bolivarian Process.

The emergence of the campesinos in the public arena is very important. Indeed, it is the most important political event in recent times.

Campesinos are a key social element in Venezuela. After all, they form part of a long struggle and they produce our food. In Venezuela, much of what we consume daily is campesino production. The old landowning class, the agribusiness sector, produces to export. The emerging agrarian Chavista bourgeoisie, which is for now midsize, does the same. Actually, even some of the campesinos’ production ends up in Colombia as a result of paramilitary networks. Campesinos have been denouncing this.

We have three very active borders in Venezuela. The one with Colombia is the most active, but we also have important borders with Brazil and with the Caribbean islands. In a small boat, you can reach many Caribbean islands. It’s very hard to control the ocean, and there is a lot of open-ocean smuggling of agricultural products. Of course, the contraband is sold in exchange for hard currency, for U.S. dollars, which is a draw.

This is a very serious problem. But despite the large amount of contraband, the fruits and vegetables that we eat daily are still produced by campesinos.

The government must sit and dialogue, as equals, with the country’s campesino organizations. The Admirable Campesino March, as important as it is, is not the only expression of campesino organization today. There are many, many campesino organizations in the country that must be heard.

There will be a Campesino Congress to address these issues. It probably won’t happen this year due to the elections. Most likely it will be next year, probably in January. The Campesino Congress must directly address class struggle in the rural areas and attempt to resolve this struggle in favor of the Venezuelan nation, in favor of the people, and, by the same token, in favor of the campesinos who produce what we eat.

To go forward, it’s important that campesino organizations develop as spaces of unity and political consciousness. They must unite the campesinos in the struggle against large landowners, pushing for an alliance with the state, making the state come to their side. If that doesn’t happen, the problem of the rural areas will not be solved, and we will not be able to solve our problems related to food supply and prices. The solution lies in the campesino bloc, which the Venezuelan state must listen to, offering real solutions.

Today, there is an open struggle between the large and medium agrarian bourgeoisie versus the campesinos. The only actor that can solve this very serious crisis in favor of the campesino bloc is the state. So the state, the government, must act! Only the state can solve this situation, as it has the police, the apparatus of repression (a part of which, by the way, is actually participating in the smuggling business and is connected to non-campesino interests).

Can you tell us more about the importance of class struggle in the countryside today?

There are two very important factors to consider today in analyzing class struggle in Venezuela. The first is a campesino bloc, which is growing in organizational terms and also making demands that are just ones. This is not a problem, we should see this as a blessing!

The second factor is the struggle between the campesinos versus the large and middle landowning class. Finally, there is [a third] factor: mercenary forces (as well as, in some cases, state forces) are participating directly, and they are not siding with the campesinos. These mercenary forces are already in action: they steal and even burn farmers’ crops.

All this is not being talked about, but it needs to be known. The violence created by non-campesino groups is leading, once again, to displacement of campesinos towards urban areas. These displaced campesinos are entering urban pockets of poverty.

We should understand that big capital and especially finance capital aims to take control of all spaces. There is a very real process of privatizing war, and that is why it is important to point to the growth of mercenary forces. We must understand that finance capital–a supranational power with local relations–is operating here.

When mercenaries come to the scene and displace campesinos, they are acting on behalf of supranational interests. The mercenary forces in Venezuela aren’t a bunch of petty criminals. They form part of an strategically organized project, and their mission is to take over the Venezuelan countryside. The class war in Venezuela has an important mercenary component.

So again, in this open and intense struggle, the government must side with the campesinos.

We know of your deep concern for the fate of the Bolivarian Process…

It is a well-known fact that Venezuela is a region of particular geopolitical interest for imperialism. This is not only because of our natural resources, which are important enough, but also because there has been a revolution here. The example set by a profound process of change is a serious problem for them.

Venezuela has been able to defeat all imperialist offensives, and that represents a challenge for them. Imperialism is intent on defeating the Bolivarian Process. That is why this process is of great importance for the peoples of the world, and if it was defeated, it would begin to close off revolutionary paths. That is why I believe that international solidarity with Venezuela is a revolutionary duty for internationalists.

Notes

- ↩ Bachaqueo refers to the widespread practice of acquiring subsidized products (i.e. cornmeal, toilet paper, etc.) and reselling them at higher prices.