Dear Friends,

Greetings from the desk of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

Andrés Manuel López Obrador–or AMLO–became the president of Mexico on 1 December. The leader of the Morena (National Regeneration Movement) party, López Obrador comes to the presidency from the left. His inaugural address laid out clearly the two reasons why half of the Mexican population lives in poverty: the neo-liberal model of economic and political governance as well as the ‘most filthy public and private corruption’. López Obrador said he would not prosecute the administration of his predecessor because ‘there would not be enough courts or jails’ for the guilty. Over the past four decades, López Obrador emphasised, Mexico has followed a disastrous policy framework–neoliberalism–which has been a calamity for the country’s public life. For a glimpse into the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research theory of neoliberalism, please read our first Working Document–In the Ruins of the Present.

One hundred and thirty million Mexicans looked towards López Obrador for some leadership. Since the Third World Debt crisis of the early 1980s, states such as Mexico have been forced by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and global financial markets to cannibalise their wealth. Mexico’s resources were gifted to gigantic international firms and to its own financial oligarchy (led by Carlos Slim Helú, one of the world’s richest men, whose wealth comes from the pillage of public resources, such as when the State delivered Telmex–Mexico’s communications monopoly–into his hands in 1990). It is worth recalling the years from the debt crisis to the fire-sale of Mexico’s public assets, which the World Bank called a ‘model’. The government sold more than eighty per cent of its 1,155 firms.

At that time, Alvaro Cepeda Neri wrote in La Jornada, ‘The booty of privatisation has made multi-millionaires of thirteen families, while the rest of the population–some eighty million Mexicans–has been subjected to the same gradual impoverishment as though they have suffered through a war’. Plunder defines Mexico’s history, from the seizure by the United States of half of Mexico’s land in 1848 (including gold-rich California) and the deflation of Mexico’s potential by NAFTA from 1994. It is too much to ask of López Obrador’s government to solve all of Mexico’s problems in one term. The new government cannot change everything. But it can start to shift the direction of state policy.

Left-wing governments in the hemisphere, under immense pressure from the United States, gathered around López Obrador for his inauguration. There was Bolivia’s Evo Morales and Cuba’s Miguel Díaz Canel. Venezuela’s Nicolas Maduro came despite immense pressure from Mexico’s right-wing and liberals to rescind his invitation. Nicaragua’s Daniel Ortega did not come. The pressure from the United States is not trivial. U.S. President Donald Trump’s administration has coined a phrase–troika of tyranny–to refer to Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela.

The United States is eager to pursue regime change in one or all of these states (as I note in my report in Frontline). Hybrid warfare is in the cards, which includes encouragement of civil rebellion and the use of social media to promote falsehoods of all kinds (for a crisp sense of the looming threats, please read John Pilger’s interview with our Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research fellows Jipson John and Jitheesh PM and please read Andrew Korybko’s Hybrid Wars, freely downloadable here). Maduro received the cold shoulder both from the right and liberals, but he was welcomed by Mexico’s trade unions. The battle lines are thickly drawn.

The image above is made by Elena Huerta Muzquiz (1908-1997), one of Mexico’s great Communist artists.

South of Mexico City, in Buenos Aires, the Group of Twenty (G20) states met, chatted amongst themselves and then withdrew to their various intractable crises. The meeting was held at the Costa Salguero convention centre–tucked away from the loud and clear voices of the protestors. The protestors came because, as the office of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research in Buenos Aires notes in its regular Bulletin and in our most recent Dossier, the economic collapse in Argentina has been steady and the Argentinian people point their fingers–like López Obrador–at the policy framework rather than at fate. When the people asked questions about the policy framework that fragmented their lives, the reply from the G20 leaders came written in tear gas. It is the language of the leadership of the G20. It is what López Obrador wants to avoid.

No real deal could come out of the G20 because the crisis of capitalism cannot be solved from within the framework of neo-liberalism. Only cosmetic changes can be made, only more can be asked of an already exhausted population around the planet.

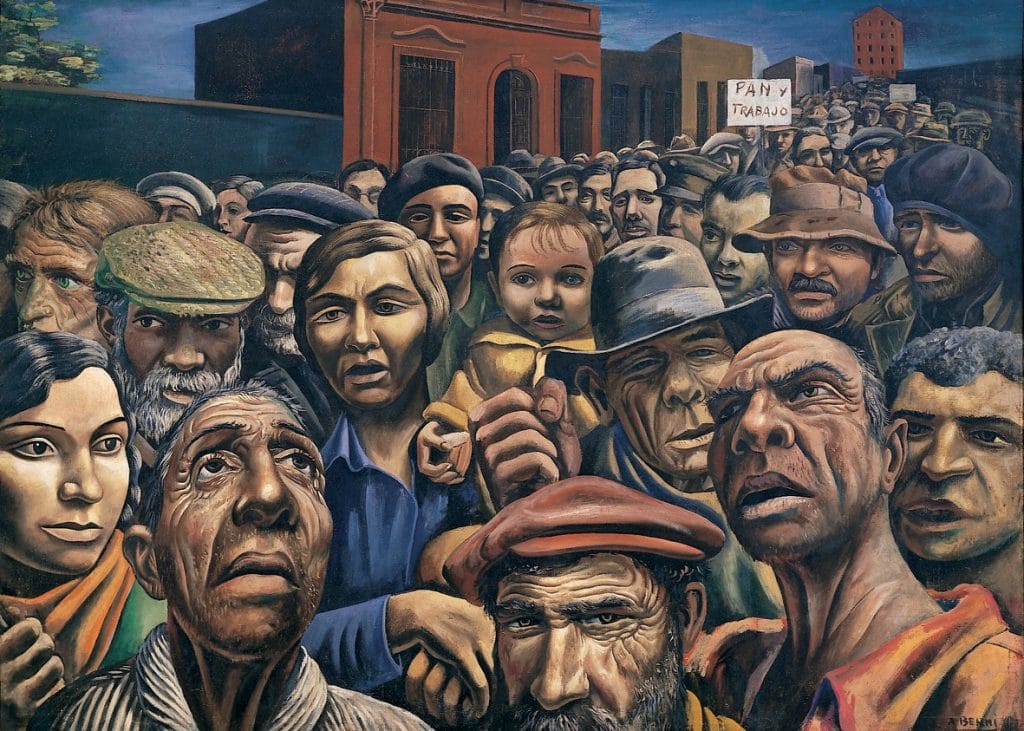

The painting above–from 1934–is by the Argentinian artist Antonio Berni (1905-1981) called Manifestación. From one demonstration at another time of financial crisis to another demonstration for our times.

South of Mexico City, in Buenos Aires, the Group of Twenty (G20) states met, chatted amongst themselves and then withdrew to their various intractable crises. The meeting was held at the Costa Salguero convention centre–tucked away from the loud and clear voices of the protestors. The protestors came because, as the office of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research in Buenos Aires notes in its regular Bulletin and in our most recent Dossier, the economic collapse in Argentina has been steady and the Argentinian people point their fingers–like López Obrador–at the policy framework rather than at fate. When the people asked questions about the policy framework that fragmented their lives, the reply from the G20 leaders came written in tear gas. It is the language of the leadership of the G20. It is what López Obrador wants to avoid.

No real deal could come out of the G20 because the crisis of capitalism cannot be solved from within the framework of neo-liberalism. Only cosmetic changes can be made, only more can be asked of an already exhausted population around the planet.

The painting above–from 1934–is by the Argentinian artist Antonio Berni (1905-1981) called Manifestación. From one demonstration at another time of financial crisis to another demonstration for our times.

A more important meeting takes place this week in Vienna (Austria) at the headquarters of the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), guarded by Austria’s elite WEGA para-military detachments. Here, Russia and Saudi Arabia came to an understanding that oil prices should be go higher. Now that the United States has strangled Iran and Venezuela, it is seen as acceptable to let oil prices drift upwards. There are no solutions here. India and China have been seriously contemplating the establishment of an oil buyers’ club (as I report here). Tensions between OPEC+ (which includes Russia) and the Asian oil buyers’, who account for a third of the world oil market, will surely produce cascading crises. The tear gas in Paris (see above) was one front of this crisis, as the population took to the streets against fuel price hikes (for background, please read Susan Ram’s report and Frèdèric Lordon’s blog post at Le Monde Diplomatique). There will be many more of these episodes over prices of fuel and over the destruction of the climate.

López Obrador, who was warned by the IMF not to intervene in the plight of Pemex–Mexico’s state-owned oil company–or to intervene with the monopoly oil firms, has now told the oil companies that if they do not invest more in exploration and production he will not allow them to expand their operations in Mexico. There are obviously ramifications to the environment by increased oil production. But this is a global problem and not one that Mexico can solve by ending oil exploration by fiat (please see our 33rd newsletter on this theme). It needs revenues from somewhere to tackle the severe problems of poverty in Mexico.

On 30 November, tens of thousands of farmers and thousands more of those who stood with them marched across Delhi to demand a parliamentary session to address their needs. One of the most resonant slogans was ayodhya nahin, karz maafi chahiye–‘Not Ayodhya. We want our debt to be written off.’ The reference is to the town of Ayodhya in northern India, where the forces of the far right (the BJP and its allies) destroyed a 16th century mosque in 1992. This year, once more, the right-wing planned to march to Ayodhya and demand that a Hindu temple be built on the ruins of the mosque. It is the nasty political dynamic that propelled Prime Minister Narendra Modi to power. The march of the farmers–led by a series of organisations including the All-India Kisan Sabha–undercut the toxicity. It forced the actual issues that prey upon the farmers and the agricultural workers on the table–high input prices, low commodity prices, predatory lenders, debt, starvation. We want our debt written off, they said, not another temple built that creates social conflict.

Our friends at the People’s Archive of Rural India and at Newsclick covered the protests, giving us a window into the lives of the farmers and agricultural workers who came to Delhi. ‘Whatever we grow’, said one of the farmers, ‘we suffer losses’. This is the outcome of the economic policy that has been a disaster.

In a short essay, the economist Prabhat Patnaik suggests that matters will deteriorate further in this period of permanent crisis. The Third World, he writes, ‘is sinking into a prolonged period of stagnation. This will bring acute distress to the working people, since the primitive accumulation of capital at the expense of the peasants and petty producers that had accompanied the capitalist boom, will continue unabated, while stagnation will only further reduce employment generation within the capitalist sector’. No solution is apparent within this policy framework–the framework that López Obrador promises Mexico will try to exit.

In our the 40th newsletter, we honoured Dr. Amit Sengupta, a long-time member of the Communist Party of India (Marxist), leader of the people’s science movement and the people’s health movement. He was also one of the organisers of the International People’s Assembly, a global network of left movements. Our image this week–below – continues our homage to Amit.

Warmly, Vijay.