Dear Friends,

Greetings from the desk of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

I come to you from Seoul (South Korea), one of the planet’s hyper-cities. Half of South Korea’s 50 million people live in the metropolitan area of Seoul. Not far from the core of the city is the demilitarised zone that cuts the Koreas in half. The political leadership of the North and South continue their brave journey to dial down the tension across the zone and to find ways to unite their peoples. Sensitive people on this peninsula want to move away from a state of permanent war. But even these small-scale unities are held back by obligations from distant lands. As far as Washington’s military and political leadership is concerned, Japan and South Korea must remain client states of the West, aircraft carriers for the encirclement of China’s return to the world stage (for context, see the first Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research Dossier from March of this year and read my most recent report here).

The glass and steel of Seoul, as with other cities on our planet, cannot hide the poverty that is tucked away in peripheral neighbourhoods and in the homes of the elderly. Earlier this year, in Lancet, a remarkable study predicted that women born in South Korea in 2030 will be the first to live for nine decades. This comes alongside OECD data that shows that half of the South Korean population over 65 live in poverty. That’s a damning statistic for a wealthy country. There was a time when South Korea seemed invincible, one of the Asian Tigers. It took a blow in 1997 with Asian financial crisis and then again in 2007-08 with the global financial crisis. Its economy faltered, its population slipped into shades of poverty and its sense of worth declined.

The social welfare net withered over the past decades as the population began to age. It is predicted that by 2030, South Korea will be one of the ‘super-aged countries’ (where one in five residents is over 65). Germany, Italy and Japan are already ‘super-aged’. The current president of South Korea–Moon Jae-in–came to power on the basis of a programme to tackle the welfare crisis in the country. His 100 Policy Tasks document (from August 2017) pledges to ‘guarantee a healthy and decent life for the elderly in preparation for an aged society’. How this will be done is to be seen. Many elderly people in South Korea give their children part of their pension; if the pension is increased, it will come out of taxes paid by those very children. Without a vigorous scheme to tax the monopoly corporations, prevent corruption by them and tax the billionaires, no resources will be available for such a benevolent project.

South Korea has a limited problem with homelessness. South Africa, on the other hand, has an endemic problem. It is rooted in the way land became a monopoly of the white population during the apartheid era and the way in which democracy after 1994 did not enter the land market. It is the absence of access to housing that leads to the creation of informal settlements, not just in South Africa but across the world. An old estimate from the United Nations suggests that at least a billion people–one in seven–live in informal settlements. A consequence of informality is the lack of services and therefore poor conditions of life. Those who live in these informal settlements are the city’s workers, priced out of more formal living arrangements by the commodification of real estate.

The United Nations’ Special Rapporteur on homelessness Leilani Farha says that the world housing market is now estimated to be worth US$163 trillion–a price that is twice that of the total world economy and vastly greater than the US$7 trillion worth of gold mined from the earth over all recorded time (please read her full report from September 2018 to the UN Human Rights Council here). Private capital has long seen the housing market as a viable investment, driving up prices. Capital sees land and housing as an investment not as a human right. This is the nub of the problem.

It is why organisations such as Abahlali baseMjondolo (AbM), the shack dwellers’ movement of South Africa, emerged in 2005 and it is why they fight–tooth and nail–to protect the rights and dignity of the workers who live in the informal settlements. The title of this newsletter–we have no choice but to live like human beings–comes from an interview that Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research did a few weeks ago with S’bu Zikode, the President of AbM. That interview is the core of our 11th Dossier–The Homemade Politics of Abahlali base Mjondolo, South Africa’s Shack Dweller Movement. It is our strongest dossier, an essential piece of reading.

The Dossier will be helpful not only in other parts of the Global South, where informal settlements form our unintended cities, but also in the Global North, where homelessness is rapidly increasing. A new report from the UK charity Shelter says that 130,000 children will be homeless over this winter. Much the same problem strikes the United States of America, where the Poor Peoples’ Campaign attempts to confront the roots of homelessness and hunger (for one example, see my recent article about the work of Arise for Social Justice).

Pay attention to Article 25 of the International Declaration of Human Rights (1948): Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control. Each year, 10 December is set aside to honour this Declaration as Human Rights Day. It is typically an overwhelming day–so many problems, so few solutions. And yet, as I write in my column this week, there are glimpses of inspiration across the world, from Marrakesh (Morocco) to Rajasthan (India).

In Marrakesh (Morocco), representatives of the world’s states met to pass a Global Compact for Migration, a promise that humane people will offer sensitive policies to desperate people. David Azia took this picture for UNHCR in Cox’s Bazar at the Kutupalong refugee settlement a few months ago.

In Oslo (Norway), Nadia Murad and Denis Mukwege shared the Nobel Peace Prize. Both Nadia and Denis are campaigners to end the use of rape as a weapon of war. They are brave people with an important message. The speech that Denis gave stayed me: ‘Turning a blind eye to tragedy is being complicit. It’s not just perpetrators of violence who are responsible for their crimes. It is also those who choose to look the other way’. A crowd of Norwegians gathered outside their hotel, holding candles as sentinels.

In India, the state elections saw the defeat of the far-right BJP party of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The elections were won, as even the BJP acknowledges, by the mass organising and struggles of farmers and peasants as well as workers from small factories to day care centres (anganwadis). It was their election. However, because the Left is weak in the main states where the elections were held, the vote of the people went to the Congress Party–less bilious in its politics, but no less callous in its approach to everyday life. Nonetheless, in Rajasthan, where the peasant movement has been strong, two peasant leaders–both Communists–won seats to the legislature.

Finally, two reports by two very brave and insightful journalists give us a little glimpse of how ordinary people become extraordinary in difficult circumstances.

Vivian Fernandes (Brazil) writes of her visit into the jungles of Colombia to meet with guerrillas of the National Liberation Army (ELN). ‘Where the transnational companies operate’, Lucia–a member of the ELN tells Vivian–‘is where the State is’. The State is the bulldozer and security guard of the monopoly firms. It does not focus on the facilitation of housing and education, health and culture for the people.

Niren Tolsi (South Africa) writes of his visit to Sri Lanka, where the insurgency has been killed off and hope lives only in the margins. Expectations are low here. Thousands of people, including children, are still missing after the horrific end to the Civil War. The Office of Missing Persons is silent. Where are our children buried, people ask? ‘Something more than nothing’, says a human rights worker.

It is a bright, cold day today. I am reading one of Korea’s great poets, Shin Kyong-nim. He reminds me of how important it is to write and speak and agitate for something better. Even in the worst days of the military dictatorship in South Korea, he wrote with feeling about the need for organisation and change. In 1973, Shin Kyong-nim published a book called Nong-mu (Farmers’ Dance). In it was this poem, The Way to Go, translated by Brother Anthony (An Sonjae):

We gathered, carrying rusty spades and picks.

In the bright moonlit grove behind the straw sack storehouse,

first we repented and swore anew,

joined shoulder to shoulder; at last we knew which way to go.

We threw away our rusty spades and picks.

Along the graveled path leading to the town

we gathered with only our empty fists and fiery breath.

We gathered with nothing but shouts and songs.

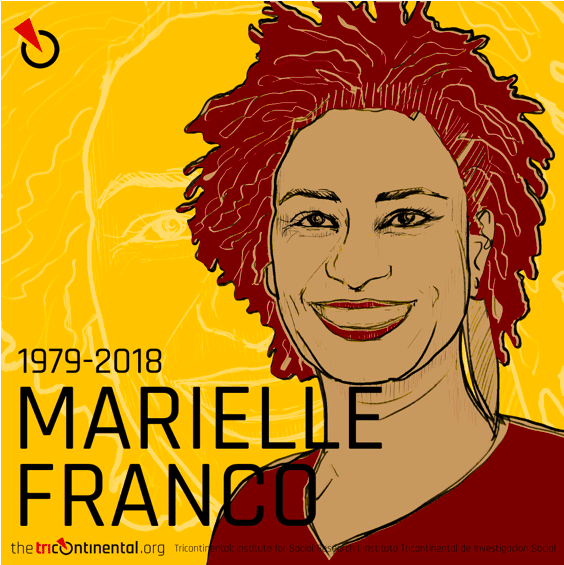

Our image this week (see below) is of Marielle Franco (1979-2018), who was killed nine months ago this week. Marielle–as she is now known–was a black woman, a socialist, a LGBTQ militant and a mother. She was born and raised in the Complex da Maré, a major favela (informal settlement) in Rio de Janeiro. After a friend was tragically shot to death in the crossfire between the police and drug traffickers, Marielle entered the world of politics. She wanted to put an end to this kind of violence. Elected as a councillor in Rio, she served as the president of the Women’s Commission. Her voice–her proud, loud voice–against violence in her home and in homes that resembled her own, such as the home of the members of AbM in South Africa, was what somebody silenced. We honour her courage and her strength and ask again, who killed Marielle? Will the killers of Marielle and Gauri Lankesh (India), Suad al-Ali (Iraq) and Hrant Dink (Turkey) and so many others be made to relinquish their chairs of authority?

Warmly, Vijay.

PS: please find our previous newsletters and dossiers, working documents and notebooks at our website in English, French, Portuguese and Spanish (with some material in Turkish!).