Greetings from the desk of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

The picture above was taken in Paris. The slogan on the wall is emblematic of the mood: we want cash while waiting for Communism. There is some of the playful anger that comes from the graffiti of 1968. There has been dance and song on the streets, there has been jubilation that finally, finally people are saying enough is enough–¡Ya basta!, as they say in Spanish–enough of being treated like an afterthought by the policy makers and the property owners. People want to be taken seriously. They want their grievances and hopes to structure the political landscape, not the avarice of corporations and the cynicism of the political class.

Susan Ram, who is writing a book on the French Left for LeftWord Books (New Delhi), has a crisp assessment of the yellow vest (gilets jaunes) movement and of its fifth week of demonstration–Act V Macron Démission (Macron Resign). It is anger and determination that defines the yellow vest protest. Attempts by President Emmanuel Macron to charm the country and by the police to smash it with a fist have been unsuccessful. The police look exhausted, Macron’s budget shudders. Prabhat Patnaik shows how Macron’s concessions are illusionary, a ‘stalling and hoodwinking tactic’. Unwilling to tax the rich, Macron will borrow to concede some demands, put France’s finances into disarray and then pretend to be sad when he or his successor enacts austerity. That is the way of neo-liberal policy makers. It is what Prabhat laid out for us in our Dossier no. 7.

We want cash, say the yellow vests, as a prelude to a radical emancipation.

In Beijing (People’s Republic of China), I meet an official–an old friend–who tells me that the yellow vest protest will have cognates everywhere, including in Asia. Neo-liberal policy has eaten society, cannibalising the sinews that link people to each other and impoverishing everyday life. This is a problem–he concedes–even in China, where the post-1949 revolutionary social forms are no longer taken seriously.

In Beijing (People’s Republic of China), I meet an official–an old friend–who tells me that the yellow vest protest will have cognates everywhere, including in Asia. Neo-liberal policy has eaten society, cannibalising the sinews that link people to each other and impoverishing everyday life. This is a problem–he concedes–even in China, where the post-1949 revolutionary social forms are no longer taken seriously.

Deng Xiaoping’s 1983 slogan–let some people get rich first (rang yi bu fen ren xian fu qi lai)–is dated. It is also misunderstood. It is easy to have a cartoon impression of China–with opinions whiplashing from the belief that China is a fully capitalist country to the belief that China is a Maoist bastion. None are fully correct. Aspirations developed by the Revolution of 1949 remain–the feeling that one need not be poor, that one should not be deprived and that one must be treated with dignity lingers. To get rich is not necessarily to become a capitalist. It has come to mean–amongst the workers–that one does not want to live for generations in poverty.

What is missing, says a senior professor, is the collective spirit produced by the Revolution of 1949. All revolutionary processes lose their energy, get sucked into the everyday problems of resource distribution and the bureaucracy of power. Reading the texts from Lenin to Ho Chi Minh to Mao Zedong that are written in the years after the revolution is instructive. All warn about this sapping of energy, this sentiment of the detachment of officials from the people. It is a problem remarked upon by China’s current premier Xi Jingping, who has championed the study of Marxism and has called for new values in governance. Channelling aspirations from individual gain to social development is not a simple matter, especially as there is a global cultural push to reduce the human personality to that of a consumer.

On Tuesday, I visited the Great Hall of the People and the National Museum of China. There is a celebration of the 40th anniversary of the reform era. In 1978, the Third Plenum of the 11th Communist Party Central Committee was held in Jingxi Hotel, down the road from Tiananmen Square. It was at this Plenum that the party’s leader Deng Xiaoping called for the opening-up of the Chinese economy and the entry of market forces into the economy. Not long after this meeting, Deng met Japan’s Prime Minister Masayoshi Ohira, whom he told that the Chinese people would be comfortable (xiaokang) by 2025. At the celebration this week, Chinese President Xi Jinping applauded three phases in Chinese modernity–the May Fourth Movement of 1911, the Revolution of 1949 and the Reform Era that began in 1978. These developments allowed China–a poor, agricultural country–to break the deep consciousness of feudal subservience and to end hunger. My report from the Great Hall and the Museum is here.

Problems remain, however, some of them very grave: the developments in Xinjiang-with the detention of unknown numbers of China’s Uyghur minority-and the arrests of Marxists students who had gone to offer solidarity to the workers of Jasic Technology in Shenzhen. It is difficult to imagine the promotion of Marxism at the same time as the violation of basic Marxist principles, such as the rights of minorities and the rights of worker organisation.

The picture above is a detail from a large ink and paint work by Tang Yongli, installed in the Museum in 2015. It depicts the first Central Committee of the Communist Party in 1949.

The gap between the dilemmas in China, at one end of Asia, and the trauma of Yemen, at Asia’s other end, is significant. Yemen remains at the edge of starvation, with more than half the population unable to survive. This is the consequence of the madness of war–the war of the Saudis and the Emiratis. Last week, a deal to dial-down the war was signed between the Yemeni factions, with no ink on the paper from the Saudis and the Emiratis. Nonetheless, the UN suggests that this might open a way forward. My column this week delves into the war. Chinese officials say that they are eager for stability in the Arabian Peninsula, the war interrupting their One Belt, One Road Initiative. Pressure from all sides on the Saudis and the Emiratis–in particular–is important. That the U.S. Senate voted not to allow the United States to be a belligerent in the war is part of this process.

The gap between the dilemmas in China, at one end of Asia, and the trauma of Yemen, at Asia’s other end, is significant. Yemen remains at the edge of starvation, with more than half the population unable to survive. This is the consequence of the madness of war–the war of the Saudis and the Emiratis. Last week, a deal to dial-down the war was signed between the Yemeni factions, with no ink on the paper from the Saudis and the Emiratis. Nonetheless, the UN suggests that this might open a way forward. My column this week delves into the war. Chinese officials say that they are eager for stability in the Arabian Peninsula, the war interrupting their One Belt, One Road Initiative. Pressure from all sides on the Saudis and the Emiratis–in particular–is important. That the U.S. Senate voted not to allow the United States to be a belligerent in the war is part of this process.

The painting above is by Hakim al-Hakel, one of Yemen’s most distinguished artists. He is now in exile in Jordan. Al-Hakel has been painting a series of portraits of Yemenis, a nostalgic aura around them. ‘I feel that the Yemeni city lives inside me’, he says.

China’s commitment to energy sources other than carbon-based ones is commendable. Countries like China, which continue to have large numbers of people with ordinary aspirations, have made it clear that they are not principally responsible for climate change and that the carbon budget that remains should give the developing countries priority. That has been the baseline position in the negotiations.

China’s commitment to energy sources other than carbon-based ones is commendable. Countries like China, which continue to have large numbers of people with ordinary aspirations, have made it clear that they are not principally responsible for climate change and that the carbon budget that remains should give the developing countries priority. That has been the baseline position in the negotiations.

It is what the ‘developed world’ denies. At the meeting in Katowice (Poland), the developing world suffered a serious defeat. T. Jayaraman and Tejal Kanitkar of the Tata Institute of Social Sciences write that the point of the negotiations has not been to tackle climate change but to ‘ensure that the world, in climate as in trade, would remain an unequal one’. ‘I believe, on further reflection’, Jayaraman said, ‘that the outcome of these talks is a strategic defeat for the vast majority of developing countries’.

On the island of Naoshima (Japan), Shinro Ohta has built part of his Shipyard Works project. The picture above is of Stern With Hole (1990). It is a premonition of what will remain after humans are extinct.

Trembles come from Brazil, where its incoming president–Jair Bolsonaro–has made reckless comments about cutting into the Amazon rain forest, the largest tropical forest in the world. The second largest rain forest is in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)–which stores 8% of global forest carbon. The DRC is rich, but its people are poor (it is ranked 176 out of 189 in the UNDP’s Human Development Index). Kambale Musavuli of Friends of the Congo tells me of the ‘continued flow of Congo’s coltan, copper, cobalt and other strategic minerals that are vital to major global industries’. You can’t read this newsletter on your smart phone without coltan. By next month, Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research will release a Notebook on the economics of the iPhone–with an eye to its place in the resource wars. War has become the smokescreen for the theft of the DRC’s resources, the impoverishment of its people and the slow attrition of its rain forest.

Trembles come from Brazil, where its incoming president–Jair Bolsonaro–has made reckless comments about cutting into the Amazon rain forest, the largest tropical forest in the world. The second largest rain forest is in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)–which stores 8% of global forest carbon. The DRC is rich, but its people are poor (it is ranked 176 out of 189 in the UNDP’s Human Development Index). Kambale Musavuli of Friends of the Congo tells me of the ‘continued flow of Congo’s coltan, copper, cobalt and other strategic minerals that are vital to major global industries’. You can’t read this newsletter on your smart phone without coltan. By next month, Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research will release a Notebook on the economics of the iPhone–with an eye to its place in the resource wars. War has become the smokescreen for the theft of the DRC’s resources, the impoverishment of its people and the slow attrition of its rain forest.

On Sunday, 23 December, the people of the DRC will go to vote for a new leader. Violence and corruption characterises the election. Kambale Musavuli asks, ‘Can the Congolese people succeed in fundamentally changing their desperate condition? They have been trapped in abject poverty and conflict by local elites who are in cahoots with multinational corporations. The riches of the Congo are being plundered’. Activists of the good side of history are disappeared. Kambale points to the determination of young people, who are often on the streets, to produce a more just DRC, a DRC that is for its 80 million people and for its land and not a DRC for its billionaires such as George Forrest and Moises Katumbi, Youssef Mansour and Jean-Pierre Bemba or a DRC for the multinational corporations such as Glencore and Banro.

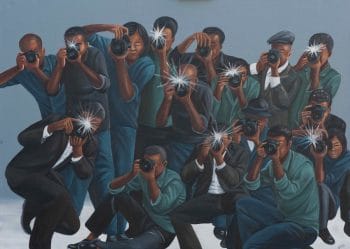

The painting above is by the DRC’s Zemba Luzamba. It is called Paparazzi. It is a little gesture here for the lack of media attention on the DRC, the epicentre of capitalism’s destruction of the planet.

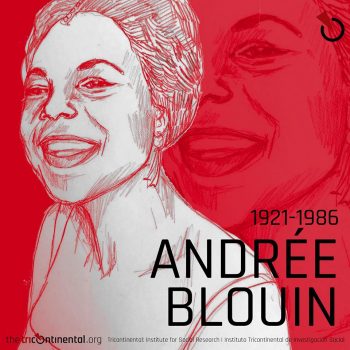

Our image below is of Andrée Blouin (1921-1986), a feminist, a pan-Africanist and an anti-colonial activist. She was instrumental in the Congolese independence struggle, serving in the first government of free Congo alongside Patrice Lumumba. ‘I want Africa to be love’, she said. ‘I speak of my country, Africa, because I want her to be known. We cannot love what we do not know. Knowing comes first, then love follows. Where there is knowledge, surely there will be love’.

Speaking of capitalism’s destructive impulses: Lisa Girion of Reuters has written an incredible story about how Johnson & Johnson (2017 revenue: US$76.5 billion) hid the carcinogenic properties in its iconic baby powder. This is a story of how the desire for profits by firms overcomes all other human emotions, such as care for the lives of human beings. The problem is asbestos–or a form of it known as tremolite. In 1969, William Ashton of Johnson & Johnson wrote to ask a company doctor, ‘Historically, in our Company, Tremolite has been bad. How bad is Tremolite medically, and how much of it can safely be in a talc base we might develop?’. The doctor replied that Tremolite should not be used. But it continued to be used, putting the ‘lungs of babies’–as the son of the founder of the company put it–at risk. It is money that is more important than the health of children. That is the moral compass of this system.

Speaking of capitalism’s destructive impulses: Lisa Girion of Reuters has written an incredible story about how Johnson & Johnson (2017 revenue: US$76.5 billion) hid the carcinogenic properties in its iconic baby powder. This is a story of how the desire for profits by firms overcomes all other human emotions, such as care for the lives of human beings. The problem is asbestos–or a form of it known as tremolite. In 1969, William Ashton of Johnson & Johnson wrote to ask a company doctor, ‘Historically, in our Company, Tremolite has been bad. How bad is Tremolite medically, and how much of it can safely be in a talc base we might develop?’. The doctor replied that Tremolite should not be used. But it continued to be used, putting the ‘lungs of babies’–as the son of the founder of the company put it–at risk. It is money that is more important than the health of children. That is the moral compass of this system.

No wonder the yellow vests in France and the farmers in India take to the streets. No wonder that the young in the DRC want to join them.

Warmly, Vijay.