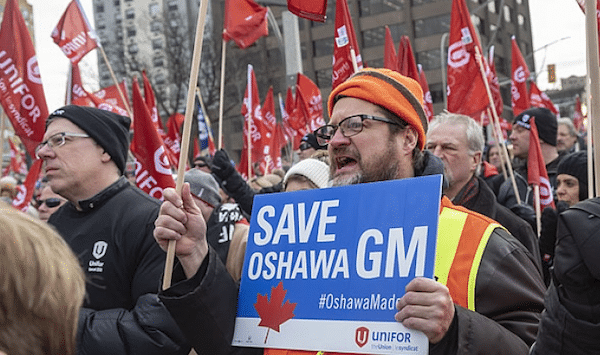

It’s become something of a shopworn cliché to say that “for every problem, there’s an opportunity.” However, I submit that this adage might well apply to General Motors’ November 26th announcement that it will be eliminating more than 14,000 jobs and closing seven factories worldwide by the end of next year, including four factories in the U.S. and one in Canada.

There is time to organize resistance. Perhaps that resistance can take the form of a militant demand that these facilities should be condemned by government authority and turned over to the workers whose labor created the wealth and profits that General Motors’ shareholders enjoy. They could then, with government assistance, be retooled and placed under the ownership and control of their workers, organized into democratic cooperatives for that purpose.

Perhaps the time has come for the nascent movement in the U.S. for genuine socialism — i.e., for democratic workers’ control of the means of production — to use the prospect of closed factories and ruined communities in Lordstown, Ohio, Baltimore, Maryland, Oshawa, Ontario, and Detroit-Hamtramck and Warren, Michigan, to organize a new manifestation of the Occupy Movement. Only this time, it could be an occupy movement that would go beyond occupying public spaces and start using legal and political mechanisms to “occupy,” own, operate and transform real facilities of production, with a view toward building genuine socialism.

There could, of course, be a direct action component to such a strategy. The United Auto Workers union became a major force for organized labor as a result of the original “occupy” movement — the great Flint sit-down strike of 1936–37, preceded by shorter sit-down strikes in Detroit and South Bend, Indiana. Broad community support from fellow workers played an instrumental role in the success of those efforts then, and could do so now, as the UAW fights to survive in the current economic landscape of transnational capitalism and runaway shops. Numbers like those achieved at the height of the Occupy Wall Street protests could help strengthen labor’s hand, especially if rank-and-file auto workers can help move the UAW away from its failed “business unionism” model and help it rediscover its militant roots.

The experience of the workers at Republic Windows and Doors in Chicago provides a contemporary illustration of the potential for economic transformation that GM is presenting today. In December 2008, over 200 workers at Republic Windows staged a sit-in to demand wages, severance pay and earned vacation time after the company shut the factory with little notice. This ultimately led to the creation of the New Era Windows Cooperative, a worker-owned cooperative democratically operated by the workers themselves, producing energy-efficient vinyl windows.

First, a little context:

Largely beneath the surface of the body politic and outside the notice of the corporate media, the beginnings of a genuine nonviolent revolutionary movement are beginning to take root in the U.S. This movement has yet to coalesce or reach critical mass, but throughout the nation, workers are coming together in various ways, organizations and venues to start building an alternative to the capitalist system.

This alternative is sometimes described as democratic socialism, eco-socialism, economic democracy, and building a “solidarity economy,” among other names. But the basic concept is this: The workers who create social wealth should have control over the economy, thereby having direct control over their economic security, as well as the political direction and economic goals of society. This control over the economy must be exercised democratically by the workers themselves, organized into associations.

These associations may take the form of workers’ or producers’ cooperatives, which in turn may be confederated and/or networked with one another in order to become stronger and eventually supplant corporate capitalism. They may take the form of community workers’ assemblies, where workers from different industries and occupations come together periodically to tackle common problems and help provide for each others’ economic security and safety at the local level. They may take the form of democratically elected and recallable workers’ councils or confederations of socialist industrial unions, as advocated by the somewhat resurgent Industrial Workers of the World or the original party of socialism in the U.S., the Socialist Labor Party.

The exact form by which workers may come to exercise control over the economy has yet to be determined; it may end up being some combination of all of the above. But growing numbers of American workers are becoming engaged in the project of building new economic institutions under workers’ control.

Some of the signs of this nascent movement include the following:

- The workers’ cooperative movement in the United States — the movement of workers to establish, or assume ownership of, individual businesses, operating them in a democratic fashion — is growing, and has led to the formation of a number of advocacy groups, federations and groups providing resources and support for workers’ cooperatives: Democracy at Work, the Democracy at Work Institute, The Foundation for Economic Democracy, the New Economy Coalition, and the U.S. Federation of Worker Cooperatives.

- The Next System Project, a project of The Democracy Collaborative, has brought together an impressive array of futuristic thinkers and social architects providing resources and ideas for creating a new economic and social order based on democratic workers’ control of production and distribution.

- In 2016, the Green Party of the United States, the most successful Left party in the United States since the Socialist and Communist parties peaked in the 1930s, adopted an eco-socialist plank in its platform, with a goal of building “an alternative economic system . . . that rejects both the capitalist system that maintains private ownership over almost all production as well as the state-socialist system that assumes control over industries without democratic, local decision making.” It now advocates a system “based on large-scale green public works, municipalization, and workplace and community democracy,” that will “end labor exploitation, environmental exploitation, and racial, gender, and wealth inequality.”

- Although the Democratic Socialists of America, as a body, still emphasizes state-run social-democratic policies and supporting candidates running within the Democratic Party, it now recognizes that “social ownership” in a future socialist society “could take many forms, such as worker-owned cooperatives or publicly owned enterprises managed by workers and consumer representatives.” Both DSA and its youth organization, YDSA, have experienced dramatic growth in the last two to three years, reflecting the growing popularity of socialist ideas among young Americans. DSA has also established an eco-socialist working group and a Solidarity Economy Network.

- There is a growing movement to build a “solidarity economy” in the U.S., which parallels and is linked with the above organizational efforts. This includes the U.S. Solidarity Economy Network and growing numbers of local community groups like Cooperation Humboldt, or, where I reside, the Carbondale Solidarity Network and related working groups. A “solidarity economy” has been defined as “an alternative development framework grounded in principles of solidarity, social equity, sustainability, democracy, and pluralism (it is not a one-size-fits-all approach). The aim is to build an economy that serves people and planet as opposed to the mainstream capitalist paradigm that is built around individual self-interest, competition, blind growth, and profit-maximizing.” There is a somewhat related movement to build sustainable intentional communities.

- The venerated socialist publication Monthly Review, under the editorship of John Bellamy Foster, has been instrumental in rediscovering and promoting the ecological wisdom in the writings of Karl Marx and has fully embraced eco-socialism. Recent works by Monthly Review writers, like Creating an Ecological Society: Toward a Revolutionary Transformation, by Fred Magdoff and Chris Williams, do a great job explaining how an eco-socialist society can be created and how it would function.

One would hope that these various groups, all moving in the same general direction, will begin to combine their efforts and find more points of convergence in the months ahead. A unified response to the shuttering of General Motors’ plants could provide a useful focal point for such a convergence.

Using eminent domain as a tool for progress

A movement to claim shuttered GM facilities as public property and place them under democratic workers’ ownership could raise the demand that state and local governments use eminent domain laws for their intended purpose of seizing private property to serve public necessity or public good.

Eminent domain law in the United States is derived from the Fifth Amendment’s “Takings” Clause, which forbids the taking of private property “for public use, without just compensation.” Implicit in the requirement to pay compensation is the notion that sovereign governments possess the inherent authority to override even vaunted private property rights when vital public purposes require it.

In its infamous Kelo v. City of New London opinion, 545 U.S. 469 (2005), the U.S. Supreme Court at once upheld that potentially revolutionary principle and perverted it — holding that a government body could use its eminent domain authority to take property away from homeowners and turn it over to private, for-profit developers. The Court’s rationale was that the anticipated benefits of economic growth make such seizures and transfers of property a permissible “public use” under the Takings Clause.

Both before and after Kelo, government bodies under capitalist influence have abused eminent domain authority in all manner of ways — to build shopping malls, golf courses, and, most maddeningly for those of us fighting climate chaos, oil and gas pipelines.

Still, when governments are captured by real representatives of working people, or at least are pressured by working people to act in the public interest, eminent domain has the potential to serve as a useful tool in the struggle to build a genuine socialist society. One illustration of that potential was provided by the Green Party’s Gayle McLaughlin and her allies when she served as mayor of Richmond, California. She used the power and threat of eminent domain as a tool against Big Finance to help homeowners avoid foreclosures in the aftermath of the housing bubble crash.

Even more on point, though, is the experience of the workers’ cooperative movement in Argentina, which successfully used a combination of occupations and legislative expropriations to greatly expand the number of what are called “recuperated enterprises” under workers’ control. Some early successes of this movement were documented in the 2004 documentary film, “The Take”, by Naomi Klein and Avi Lewis. As the authors of this highly recommended essay in Socialism and Democracy explain, the Takings Clause and eminent domain laws provide essentially “the same legal mechanism as [exists in] Argentina for promoting worker-owned and worker-managed enterprises.” They observe how workers in Argentina “have shown that they can successfully manage metal plants, tire factories, food processors, chemical plants, meat-packing plants, textile factories, auto parts installations, electronic component suppliers, ceramic factories, lumber factories, glass factories, supermarkets, printers and publishers, health clinics, hospitals, schools and hotels.”

Recuperation of GM properties is especially justified

Three additional historical factors especially justify recuperation of GM facilities. One is that the planned layoffs come in the wake of the 2008 taxpayer bailout of GM — which left U.S. taxpayers with a net loss of $11.3 billion when the federal government sold back its final shares in December 2013. The Canadian government also helped bail out GM, and is out about $3 billion. “We the people” are still out quite a bit of money on the bailout; therefore, we the people have a moral and just claim for additional compensation. How about giving us the plants?

Second, the UAW made major concessions to GM in 2009, sacrificing pay and bonuses in order to help save the company. Indeed, the union has regularly been making concessions to GM and other auto corporations since 1979, with agreement after agreement promising job security while the number of UAW members at GM went from 450,000 to a level of only 50,000 today. The new planned layoffs are yet another slap in the face to auto workers and their union. The auto workers’ concessions provide additional moral grounds for compensation.

Third, workers have especially good cause for possession of the Hamtramck assembly plant: Eminent domain was used to give that property to GM in the first place! In 1981, the City of Detroit used the power of eminent domain to forcibly displace 4,000 residents from what used to be known as the Poletown neighborhood — destroying numerous homes, businesses, churches, and schools — based in part on promises by GM and city officials that 6,000 jobs would be created. As George Mason University Professor of Law Ilya Somin points out in this excellent summary, not only did GM fail to keep its promise; in addition, “local, state, and federal governments spent some $250 million in public funds on the project (GM paid only $8 million to acquire the land).” Now, 37 years after this double whammy “taking,” GM has the gall to announce that the number of workers employed at Hamtramck will be brought down to zero.

If the reader will forgive another cliché, turnabout is fair play. The City of Detroit now has an opportunity to use eminent domain to do public good for a change and help advance the cause of building the kinds of new economic institutions needed to supplant the capitalist system that is ravaging the planet.

In proposing a workers’ takeover and operation of GM’s facilities as worker-owned cooperatives, I am not suggesting that they necessarily continue manufacturing the same vehicles that GM has already determined are not selling well enough to justify continued production. Rather, if the plants are to be taken over by and for the workers, in the public interest, they should also be used to serve the broader public good. I would suggest reviving the proposal made by Michael Moore (and others) when GM was heading into bankruptcy proceedings in 2009: Since there was, and still is, a compelling need to address the climate crisis, major public funds should be used to “immediately convert our auto factories to factories that build mass transit vehicles and alternative energy devices.”

Moore compared his proposal to the major effort used during World War II, when “GM halted all car production and immediately used the assembly lines to build planes, tanks and machine guns,” a conversion that “took no time at all.” Today the preferred metaphor is the Green New Deal, but the concept is the same: We should demand that public funds be used to help new owners of these facilities — democratically run workers’ cooperatives — convert them to build energy efficient public mass transit vehicles or other devices that serve the purpose of addressing the climate crisis.

For this to work, the first step is to win the support of the workers most immediately affected by the threatened closures, the present employees in these plants. They must be presented with and persuaded to adopt a strategy to occupy, recuperate, convert and operate these GM plants under their own democratic collective ownership. The various movement groups identified in this article that favor eco-socialism and a solidarity economy, especially those with local groups in Michigan, Ohio, Ontario and Maryland, should be encouraged to engage these workers, their local unions and their surrounding communities, and seek to win them over to such a strategy.

I move to adopt this proposal. Do I hear a second?

Rich Whitney, is an attorney, disk jockey, environmental and peace activist, co-chair of the Illinois Green Party, eco-socialist, IWW member, and advocate for genuine political and economic democracy.