Before the fateful day of January 22, fewer than one in five Venezuelans had heard of Juan Guaidó. Only a few months ago, the 35-year-old was an obscure character in a politically marginal far-right group closely associated with gruesome acts of street violence. Even in his own party, Guaidó had been a mid-level figure in the opposition-dominated National Assembly, which is now held under contempt according to Venezuela’s constitution.

But after a single phone call from from U.S. Vice President Mike Pence, Guaidó proclaimed himself president of Venezuela. Anointed as the leader of his country by Washington, a previously unknown political bottom-dweller was vaulted onto the international stage as the U.S.-selected leader of the nation with the world’s largest oil reserves.

Echoing the Washington consensus, the New York Times editorial board hailed Guaidó as a “credible rival” to Maduro with a “refreshing style and vision of taking the country forward.” The Bloomberg News editorial board applauded him for seeking “restoration of democracy” and the Wall Street Journal declared him “a new democratic leader.” Meanwhile, Canada, numerous European nations, Israel, and the bloc of right-wing Latin American governments known as the Lima Group recognized Guaidó as the legitimate leader of Venezuela.

While Guaidó seemed to have materialized out of nowhere, he was, in fact, the product of more than a decade of assiduous grooming by the U.S. government’s elite regime change factories. Alongside a cadre of right-wing student activists, Guaidó was cultivated to undermine Venezuela’s socialist-oriented government, destabilize the country, and one day seize power. Though he has been a minor figure in Venezuelan politics, he had spent years quietly demonstrated his worthiness in Washington’s halls of power.

“Juan Guaidó is a character that has been created for this circumstance,” Marco Teruggi, an Argentinian sociologist and leading chronicler of Venezuelan politics, told The Grayzone. “It’s the logic of a laboratory–Guaidó is like a mixture of several elements that create a character who, in all honesty, oscillates between laughable and worrying.”

Diego Sequera, a Venezuelan journalist and writer for the investigative outlet Misión Verdad, agreed: “Guaidó is more popular outside Venezuela than inside, especially in the elite Ivy League and Washington circles,” Sequera remarked to The Grayzone, “He’s a known character there, is predictably right-wing, and is considered loyal to the program.”

While Guaidó is today sold as the face of democratic restoration, he spent his career in the most violent faction of Venezuela’s most radical opposition party, positioning himself at the forefront of one destabilization campaign after another. His party has been widely discredited inside Venezuela, and is held partly responsible for fragmenting a badly weakened opposition.

“‘These radical leaders have no more than 20 percent in opinion polls,” wrote Luis Vicente León, Venezuela’s leading pollster. According to León, Guaidó’s party remains isolated because the majority of the population “does not want war. ‘What they want is a solution.’”

But this is precisely why Guaidó was selected by Washington: He is not expected to lead Venezuela toward democracy, but to collapse a country that for the past two decades has been a bulwark of resistance to U.S. hegemony. His unlikely rise signals the culmination of a two decades-long project to destroy a robust socialist experiment.

Targeting the “troika of tyranny”

Since the 1998 election of Hugo Chávez, the United States has fought to restore control over Venezuela and is vast oil reserves. Chávez’s socialist programs may have redistributed the country’s wealth and helped lift millions out of poverty, but they also earned him a target on his back.

In 2002, Venezuela’s right-wing opposition briefly ousted Chávez with U.S. support and recognition, before the military restored his presidency following a mass popular mobilization. Throughout the administrations of U.S. Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama, Chávez survived numerous assassination plots, before succumbing to cancer in 2013. His successor, Nicolas Maduro, has survived three attempts on his life.

The Trump administration immediately elevated Venezuela to the top of Washington’s regime change target list, branding it the leader of a “troika of tyranny.” Last year, Trump’s national security team attempted to recruit members of the military brass to mount a military junta, but that effort failed.

According to the Venezuelan government, the U.S. was also involved in a plot, codenamed Operation Constitution, to capture Maduro at the Miraflores presidential palace; and another, called Operation Armageddon, to assassinate him at a military parade in July 2017. Just over a year later, exiled opposition leaders tried and failed to kill Maduro with drone bombs during a military parade in Caracas.

More than a decade before these intrigues, a group of right-wing opposition students were hand-selected and groomed by an elite US-funded regime change training academy to topple Venezuela’s government and restore the neoliberal order.

Training from the “‘export-a-revolution’ group that sowed the seeds for a NUMBER of color revolutions”

On October 5, 2005, with Chávez’s popularity at its peak and his government planning sweeping socialist programs, five Venezuelan “student leaders” arrived in Belgrade, Serbia to begin training for an insurrection.

The students had arrived from Venezuela courtesy of the Center for Applied Non-Violent Action and Strategies, or CANVAS. This group is funded largely through the National Endowment for Democracy, a CIA cut-out that functions as the U.S. government’s main arm of promoting regime change; and offshoots like the International Republican Institute and the National Democratic Institute for International Affairs. According to leaked internal emails from Stratfor, an intelligence firm known as the “shadow CIA,” CANVAS “may have also received CIA funding and training during the 1999/2000 anti-Milosevic struggle.”

CANVAS is a spinoff of Otpor, a Serbian protest group founded by Srdja Popovic in 1998 at the University of Belgrade. Otpor, which means “resistance” in Serbian, was the student group that gained international fame—and Hollywood-level promotion—by mobilizing the protests that eventually toppled Slobodan Milosevic.

This small cell of regime change specialists was operating according to the theories of the late Gene Sharp, the so-called “Clausewitz of non-violent struggle.” Sharp had worked with a former Defense Intelligence Agency analyst, Col. Robert Helvey, to conceive a strategic blueprint that weaponized protest as a form of hybrid warfare, aiming it at states that resisted Washington’s unipolar domination.

Otpor was supported by the National Endowment for Democracy, USAID, and Sharp’s Albert Einstein Institute. Sinisa Sikman, one of Otpor’s main trainers, once said the group even received direct CIA funding.

According to a leaked email from a Stratfor staffer, after running Milosevic out of power, “the kids who ran OTPOR grew up, got suits and designed CANVAS… or in other words a ‘export-a-revolution’ group that sowed the seeds for a NUMBER of color revolutions. They are still hooked into U.S. funding and basically go around the world trying to topple dictators and autocratic governments (ones that U.S. does not like ;).”

Stratfor revealed that CANVAS “turned its attention to Venezuela” in 2005, after training opposition movements that led pro-NATO regime change operations across Eastern Europe.

While monitoring the CANVAS training program, Stratfor outlined its insurrectionist agenda in strikingly blunt language: “Success is by no means guaranteed, and student movements are only at the beginning of what could be a years-long effort to trigger a revolution in Venezuela, but the trainers themselves are the people who cut their teeth on the ‘Butcher of the Balkans.’ They’ve got mad skills. When you see students at five Venezuelan universities hold simultaneous demonstrations, you will know that the training is over and the real work has begun.”

Birthing the “Generation 2007” regime change cadre

The “real work” began two years later, in 2007, when Guaidó graduated from Andrés Bello Catholic University of Caracas. He moved to Washington, DC to enroll in the Governance and Political Management Program at George Washington University, under the tutelage of Venezuelan economist Luis Enrique Berrizbeitia, one of the top Latin American neoliberal economists. Berrizbeitia is a former executive director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) who spent more than a decade working in the Venezuelan energy sector, under the old oligarchic regime that was ousted by Chávez.

That year, Guaidó helped lead anti-government rallies after the Venezuelan government declined to to renew the license of Radio Caracas Televisión (RCTV). This privately owned station played a leading role in the 2002 coup against Hugo Chávez. RCTV helped mobilize anti-government demonstrators, falsified information blaming government supporters for acts of violence carried out by opposition members, and banned pro-government reporting amid the coup. The role of RCTV and other oligarch-owned stations in driving the failed coup attempt was chronicled in the acclaimed documentary The Revolution Will Not Be Televised.

That same year, the students claimed credit for stymying Chavez’s constitutional referendum for a “21st century socialism” that promised “to set the legal framework for the political and social reorganization of the country, giving direct power to organized communities as a prerequisite for the development of a new economic system.”

From the protests around RCTV and the referendum, a specialized cadre of US-backed class of regime change activists was born. They called themselves “Generation 2007.”

The Stratfor and CANVAS trainers of this cell identified Guaidó’s ally–a street organizer named Yon Goicoechea–as a “key factor” in defeating the constitutional referendum. The following year, Goicochea was rewarded for his efforts with the Cato Institute’s Milton Friedman Prize for Advancing Liberty, along with a $500,000 prize, which he promptly invested into building his own Liberty First (Primero Justicia) political network.

Friedman, of course, was the godfather of the notorious neoliberal Chicago Boys who were imported into Chile by dictatorial junta leader Augusto Pinochet to implement policies of radical “shock doctrine”-style fiscal austerity. And the Cato Institute is the libertarian Washington DC-based think tank founded by the Koch Brothers, two top Republican Party donors who have become aggressive supporters of the right-wing across Latin America.

Friedman, of course, was the godfather of the notorious neoliberal Chicago Boys who were imported into Chile by dictatorial junta leader Augusto Pinochet to implement policies of radical “shock doctrine”-style fiscal austerity. And the Cato Institute is the libertarian Washington DC-based think tank founded by the Koch Brothers, two top Republican Party donors who have become aggressive supporters of the right-wing across Latin America.

Wikileaks published a 2007 email from American ambassador to Venezuela William Brownfield sent to the State Department, National Security Council and Department of Defense Southern Command praising “Generation of ’07” for having “forced the Venezuelan president, accustomed to setting the political agenda, to (over)react.” Among the “emerging leaders” Brownfield identified were Freddy Guevara and Yon Goicoechea. He applauded the latter figure as “one of the students’ most articulate defenders of civil liberties.”

Flush with cash from libertarian oligarchs and U.S. government soft power outfits, the radical Venezuelan cadre took their Otpor tactics to the streets, along with a version of the group’s logo, as seen below:

Flush with cash from libertarian oligarchs and U.S. government soft power outfits, the radical Venezuelan cadre took their Otpor tactics to the streets, along with a version of the group’s logo, as seen below:

“Galvanizing public unrest…to take advantage of the situation and spin it against Chavez”

In 2009, the Generation 2007 youth activists staged their most provocative demonstration yet, dropping their pants on public roads and aping the outrageous guerrilla theater tactics outlined by Gene Sharp in his regime change manuals. The protesters had mobilized against the arrest of an ally from another newfangled youth group called JAVU. This far-right group “gathered funds from a variety of U.S. government sources, which allowed it to gain notoriety quickly as the hardline wing of opposition street movements,” according to academic George Ciccariello-Maher’s book, “Building the Commune.”

While video of the protest is not available, many Venezuelans have identified Guaidó as one of its key participants. While the allegation is unconfirmed, it is certainly plausible; the bare-buttocks protesters were members of the Generation 2007 inner core that Guaidó belonged to, and were clad in their trademark Resistencia! Venezuela t-shirts, as seen below:

That year, Guaidó exposed himself to the public in another way, founding a political party to capture the anti-Chavez energy his Generation 2007 had cultivated. Called Popular Will, it was led by Leopoldo López, a Princeton-educated right-wing firebrand heavily involved in National Endowment for Democracy programs and elected as the mayor of a district in Caracas that was one of the wealthiest in the country. Lopez was a portrait of Venezuelan aristocracy, directly descended from his country’s first president. He was also the first cousin of Thor Halvorssen, founder of the U.S.-based Human Rights Foundation that functions as a de facto publicity shop for U.S.-backed anti-government activists in countries targeted by Washington for regime change.

Though Lopez’s interests aligned neatly with Washington’s, U.S. diplomatic cables published by Wikileaks highlighted the fanatical tendencies that would ultimately lead to Popular Will’s marginalization. One cable identified Lopez as “a divisive figure within the opposition… often described as arrogant, vindictive, and power-hungry.” Others highlighted his obsession with street confrontations and his “uncompromising approach” as a source of tension with other opposition leaders who prioritized unity and participation in the country’s democratic institutions.

By 2010, Popular Will and its foreign backers moved to exploit the worst drought to hit Venezuela in decades. Massive electricity shortages had struck the country due the dearth of water, which was needed to power hydroelectric plants. A global economic recession and declining oil prices compounded the crisis, driving public discontentment.

Stratfor and CANVAS–key advisors of Guaidó and his anti-government cadre–devised a shockingly cynical plan to drive a dagger through the heart of the Bolivarian revolution. The scheme hinged on a 70% collapse of the country’s electrical system by as early as April 2010.

“This could be the watershed event, as there is little that Chavez can do to protect the poor from the failure of that system,” the Stratfor internal memo declared. “This would likely have the impact of galvanizing public unrest in a way that no opposition group could ever hope to generate. At that point in time, an opposition group would be best served to take advantage of the situation and spin it against Chavez and towards their needs.”

By this point, the Venezuelan opposition was receiving a staggering $40-50 million a year from U.S. government organizations like USAID and the National Endowment for Democracy, according to a report by the Spanish think tank, the FRIDE Institute. It also had massive wealth to draw on from its own accounts, which were mostly outside the country.

While the scenario envisioned by Statfor did not come to fruition, the Popular Will party activists and their allies cast aside any pretense of non-violence and joined a radical plan to destabilize the country.

Towards violent destabilization

In November, 2010, according to emails obtained by Venezuelan security services and presented by former Justice Minister Miguel Rodríguez Torres, Guaidó, Goicoechea, and several other student activists attended a secret five-day training at the Fiesta Mexicana hotel in Mexico City. The sessions were run by Otpor, the Belgrade-based regime change trainers backed by the U.S. government. The meeting had reportedly received the blessing of Otto Reich, a fanatically anti-Castro Cuban exile working in George W. Bush’s Department of State, and the right-wing former Colombian President Alvaro Uribe.

At the Fiesta Mexicana hotel, the emails stated, Guaidó and his fellow activists hatched a plan to overthrow President Hugo Chavez by generating chaos through protracted spasms of street violence.

Three petroleum industry figureheads–Gustavo Torrar, Eligio Cedeño and Pedro Burelli–allegedly covered the $52,000 tab to hold the meeting. Torrar is a self-described “human rights activist” and “intellectual” whose younger brother Reynaldo Tovar Arroyo is the representative in Venezuela of the private Mexican oil and gas company Petroquimica del Golfo, which holds a contract with the Venezuelan state.

Cedeño, for his part, is a fugitive Venezuelan businessman who claimed asylum in the United States, and Pedro Burelli a former JP Morgan executive and the former director of Venezuela’s national oil company, Petroleum of Venezuela (PDVSA). He left PDVSA in 1998 as Hugo Chavez took power and is on the advisory committee of Georgetown University’s Latin America Leadership Program.

Burelli insisted that the emails detailing his participation had been fabricated and even hired a private investigator to prove it. The investigator declared that Google’s records showed the emails alleged to be his were never transmitted.

Yet today Burelli makes no secret of his desire to see Venezuela’s current president, Nicolás Maduro, deposed–and even dragged through the streets and sodomized with a bayonet, as Libyan leader Moammar Qaddafi was by NATO-backed militiamen.

.@NicolasMaduro, jamas me has hecho caso. Me has fustigado/perseguido como @chavezcandanga jamás osó. Óyeme, tienes sólo dos opciones en las próximas 24 horas:

1. Como Noriega: pagar pena por narcotráfico y luego a @IntlCrimCourt La Haya por DDHH.

2. O a la Gaddafi.

Escoge ya! pic.twitter.com/pMksCEXEmY

— Pedro Mario Burelli (@pburelli) January 17, 2019

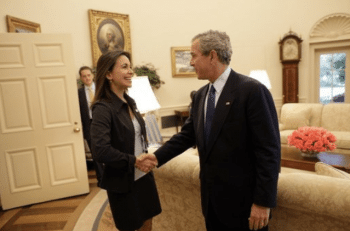

The alleged Fiesta Mexicana plot flowed into another destabilization plan revealed in a series of documents produced by the Venezuelan government. In May 2014, Caracas released documents detailing an assassination plot against President Nicolás Maduro. The leaks identified the Miami-based Maria Corina Machado as a leader of the scheme. A hardliner with a penchant for extreme rhetoric, Machado has functioned as an international liaison for the opposition, visiting President George W. Bush in 2005.

“I think it is time to gather efforts; make the necessary calls, and obtain financing to annihilate Maduro and the rest will fall apart,” Machado wrote in an email to former Venezuelan diplomat Diego Arria in 2014.

“I think it is time to gather efforts; make the necessary calls, and obtain financing to annihilate Maduro and the rest will fall apart,” Machado wrote in an email to former Venezuelan diplomat Diego Arria in 2014.

In another email, Machado claimed that the violent plot had the blessing of U.S. Ambassador to Colombia, Kevin Whitaker. “I have already made up my mind and this fight will continue until this regime is overthrown and we deliver to our friends in the world. If I went to San Cristobal and exposed myself before the OAS, I fear nothing. Kevin Whitaker has already reconfirmed his support and he pointed out the new steps. We have a checkbook stronger than the regime’s to break the international security ring.”

Guaidó heads to the barricades

That February, student demonstrators acting as shock troops for the exiled oligarchy erected violent barricades across the country, turning opposition-controlled quarters into violent fortresses known as guarimbas. While international media portrayed the upheaval as a spontaneous protest against Maduro’s iron-fisted rule, there was ample evidence that Popular Will was orchestrating the show.

“None of the protesters at the universities wore their university t-shirts, they all wore Popular Will or Justice First t-shirts,” a guarimba participant said at the time. “They might have been student groups, but the student councils are affiliated to the political opposition parties and they are accountable to them.”

Asked who the ringleaders were, the guarimba participant said, “Well if I am totally honest, those guys are legislators now.”

Around 43 were killed during the 2014 guarimbas. Three years later, they erupted again, causing mass destruction of public infrastructure, the murder of government supporters, and the deaths of 126 people, many of whom were Chavistas. In several cases, supporters of the government were burned alive by armed gangs.

Guaidó was directly involved in the 2014 guarimbas. In fact, he tweeted video showing himself clad in a helmet and gas mask, surrounded by masked and armed elements that had shut down a highway that were engaging in a violent clash with the police. Alluding to his participation in Generation 2007, he proclaimed, “I remember in 2007, we proclaimed, ‘Students!’ Now, we shout, ‘Resistance! Resistance!’”

Guaidó has deleted the tweet, demonstrating apparent concern for his image as a champion of democracy.

On February 12, 2014, during the height of that year’s guarimbas, Guaidó joined Lopez on stage at a rally of Popular Will and Justice First. During a lengthy diatribe against the government, Lopez urged the crowd to march to the office of Attorney General Luisa Ortega Diaz. Soon after, Diaz’s office came under attack by armed gangs who attempted to burn it to the ground. She denounced what she called “planned and premeditated violence.”

In an televised appearance in 2016, Guaidó dismissed deaths resulting from guayas–a guarimba tactic involving stretching steel wire across a roadway in order to injure or kill motorcyclists–as a “myth.” His comments whitewashed a deadly tactic that had killed unarmed civilians like Santiago Pedroza and decapitated a man named Elvis Durán, among many others.

This callous disregard for human life would define his Popular Will party in the eyes of much of the public, including many opponents of Maduro.

Cracking down on Popular Will

As violence and political polarization escalated across the country, the government began to act against the Popular Will leaders who helped stoke it.

Freddy Guevara, the National Assembly Vice-President and second in command of Popular Will, was a principal leader in the 2017 street riots. Facing a trial for his role in the violence, Guevara took shelter in the Chilean embassy, where he remains.

Lester Toledo, a Popular Will legislator from the state of Zulia, was wanted by Venezuelan government in September 2016 on charges of financing terrorism and plotting assassinations. The plans were said to be made with former Colombian President Álavaro Uribe. Toledo escaped Venezuela and went on several speaking tours with Human Rights Watch, the U.S. government-backed Freedom House, the Spanish Congress and European Parliament.

Carlos Graffe, another Otpor-trained Generation 2007 member who led Popular Will, was arrested in July 2017. According to police, he was in possession of a bag filled with nails, C4 explosives and a detonator. He was released on December 27, 2017.

Leopoldo Lopez, the longtime Popular Will leader, is today under house arrest, accused of a key role in deaths of 13 people during the guarimbas in 2014. Amnesty International lauded Lopez as a “prisoner of conscience” and slammed his transfer from prison to house as “not good enough.” Meanwhile, family members of guarimba victims introduced a petition for more charges against Lopez.

Yon Goicoechea, the Koch Brothers posterboy and US-backed founder of Justice First, was arrested in 2016 by security forces who claimed they found found a kilo of explosives in his vehicle. In a New York Times op-ed, Goicoechea protested the charges as “trumped-up” and claimed he had been imprisoned simply for his “dream of a democratic society, free of Communism.” He was freed in November 2017.

Hoy, en Caricuao. Llevo 15 años trabajando con @jguaido. Confío en él. Conozco la constancia y la inteligencia con la que se ha construido a sí mismo. Está haciendo las cosas con bondad, pero sin ingenuidad. Hay una posibilidad abierta hacia la libertad. pic.twitter.com/Lidm8y5RTX

— Yon Goicoechea (@YonGoicoechea) January 20, 2019

David Smolansky, also a member of the original Otpor-trained Generation 2007, became Venezuela’s youngest-ever mayor when he was elected in 2013 in the affluent suburb of El Hatillo. But he was stripped of his position and sentenced to 15 months in prison by the Supreme Court after it found him culpable of stirring the violent guarimbas.

Facing arrest, Smolansky shaved his beard, donned sunglasses and slipped into Brazil disguised as a priest with a bible in hand and rosary around his neck. He now lives in Washington, DC, where he was hand picked by Secretary of the Organization of American States Luis Almagro to lead the working group on the Venezuelan migrant and refugee crisis.

This July 26, Smolansky held what he called a “cordial reunion” with Elliot Abrams, the convicted Iran-Contra felon installed by Trump as special U.S. envoy to Venezuela. Abrams is notorious for overseeing the U.S. covert policy of arming right-wing death squads during the 1980’s in Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Guatemala. His lead role in the Venezuelan coup has stoked fears that another blood-drenched proxy war might be on the way.

Cordial reunión en la ONU con Elliott Abrams, enviado especial del gobierno de EEUU para Venezuela. Reiteramos que la prioridad para el gobierno interino que preside @jguaido es la asistencia humanitaria para millones de venezolanos que sufren de la falta de comida y medicinas. pic.twitter.com/vHfktVKgV4

— David Smolansky (@dsmolansky) January 26, 2019

Four days earlier, Machado rumbled another violent threat against Maduro, declaring that if he “wants to save his life, he should understand that his time is up.”

A pawn in their game

The collapse of Popular Will under the weight of the violent campaign of destabilization it ran alienated large sectors of the public and wound much of its leadership up in exile or in custody. Guaidó had remained a relatively minor figure, having spent most of his nine-year career in the National Assembly as an alternate deputy. Hailing from one of Venezuela’s least populous states, Guaidó came in second place during the 2015 parliamentary elections, winning just 26% of votes cast in order to secure his place in the National Assembly. Indeed, his bottom may have been better known than his face.

Guaidó is known as the president of the opposition-dominated National Assembly, but he was never elected to the position. The four opposition parties that comprised the Assembly’s Democratic Unity Table had decided to establish a rotating presidency. Popular Will’s turn was on the way, but its founder, Lopez, was under house arrest. Meanwhile, his second-in-charge, Guevara, had taken refuge in the Chilean embassy. A figure named Juan Andrés Mejía would have been next in line but reasons that are only now clear, Juan Guaido was selected.

“There is a class reasoning that explains Guaidó’s rise,” Sequera, the Venezuelan analyst, observed. “Mejía is high class, studied at one of the most expensive private universities in Venezuela, and could not be easily marketed to the public the way Guaidó could. For one, Guaidó has common mestizo features like most Venezuelans do, and seems like more like a man of the people. Also, he had not been overexposed in the media, so he could be built up into pretty much anything.”

In December 2018, Guaidó sneaked across the border and junketed to Washington, Colombia and Brazil to coordinate the plan to hold mass demonstrations during the inauguration of President Maduro. The night before Maduro’s swearing-in ceremony, both Vice President Mike Pence and Canadian Foreign Minister Chrystia Freeland called Guaidó to affirm their support.

A week later, Sen. Marco Rubio, Sen. Rick Scott and Rep. Mario Diaz-Balart–all lawmakers from the Florida base of the right-wing Cuban exile lobby–joined President Trump and Vice President Pence at the White House. At their request, Trump agreed that if Guaidó declared himself president, he would back him.

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo met personally withGuaidó on January 10, according to the Wall Street Journal. However, Pompeo could not pronounce Guaidó’s name when he mentioned him in a press briefing on January 25, referring to him as “Juan Guido.”

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo just called the figure Washington is attempting to install as Venezuelan President "Juan *Guido*" – as in the racist term for Italians. America's top diplomat didn't even bother to learn how to pronounce his puppet's name. pic.twitter.com/HsanZXuSPR

— Dan Cohen (@dancohen3000) January 25, 2019

By January 11, Guaidó’s Wikipedia page had been edited 37 times, highlighting the struggle to shape the image of a previously anonymous figure who was now a tableau for Washington’s regime change ambitions. In the end, editorial oversight of his page was handed over to Wikipedia’s elite council of “librarians,” who pronounced him the “contested” president of Venezuela.

Guaidó might have been an obscure figure, but his combination of radicalism and opportunism satisfied Washington’s needs. “That internal piece was missing,” a Trump administration said of Guaidó. “He was the piece we needed for our strategy to be coherent and complete.”

“For the first time,” Brownfield, the former American ambassador to Venezuela, gushed to the New York Times, “you have an opposition leader who is clearly signaling to the armed forces and to law enforcement that he wants to keep them on the side of the angels and with the good guys.”

But Guaidó’s Popular Will party formed the shock troops of the guarimbas that caused the deaths of police officers and common citizens alike. He had even boasted of his own participation in street riots. And now, to win the hearts and minds of the military and police, Guaido had to erase this blood-soaked history.

On January 21, a day before the coup began in earnest, Guaidó’s wife delivered a video address calling on the military to rise up against Maduro. Her performance was wooden and uninspiring, underscoring the her husband’s limited political prospects.

At a press conference before supporters four days later, Guaidó announced his solution to the crisis: “Authorize a humanitarian intervention!”

While he waits on direct assistance, Guaidó remains what he has always been–a pet project of cynical outside forces. “It doesn’t matter if he crashes and burns after all these misadventures,” Sequera said of the coup figurehead. “To the Americans, he is expendable.”