Every time a progressive policy captures the public imagination, like the Green New Deal, opponents are quick to raise the revenue question in an effort to discredit it. While higher taxes on the wealthy and leading corporations should be an obvious starting point in any response, until recently elites have been remarkably successful in winning tax reductions, spinning the argument that cuts are the best way to stimulate private investment and create jobs. And they have enjoyed a double gain: not only do the cuts benefit them financially, the loss of public revenue encourages people to think small when it comes to public policy.

However, there are signs that the times might be changing. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s proposal to tax annual incomes over $10 million at a marginal tax rate of 70 percent has won significant public support. Strong popular opposition in New York to a plan to heavily subsidize a new Amazon headquarters forced the company to withdraw its proposal. And then there is the negative lesson of the Wisconsin fiasco, where the state showered Foxconn with massive tax and other subsidies in an effort to land a new manufacturing facility, only to have the company walk-back its commitments after significant state expenditures.

But there is still important education as well as political work that remains to be done to win majority support for the kind of tax reform we so desperately need. President Trump’s “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” which was signed into law on Dec. 22, 2017, is one example of what we are up against.

The “American model”

President Trump’s signature tax law included significant benefits for the wealthy as well as most major corporations. Looking just at the business side, the law:

- lowered the U.S. corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent and eliminated the corporate Alternative Minimum Tax.

- changed the federal tax system from a global to a territorial one. Under the previous global tax system, U.S. multinational corporations were supposed to pay the 35 percent U.S. tax rate for income earned in any country in which they had a subsidiary, less a credit for the income taxes they paid to that country. However, the tax payment could be deferred until the earnings were repatriated. Under the new territorial tax system, each corporate subsidiary only has to pay the tax rate of the country in which it is legally established; foreign profits face no additional U.S. taxes.

- established a new “global minimum” tax of 10.5 percent that is only applied to total foreign earnings greater than a newly established “normal rate of return” on tangible investments in plant and equipment (set at 10 percent).

- offered multinational corporations a one-time special lower tax rate of 8 percent on repatriated funds that were held overseas by corporate subsidiaries in tax-haven countries.

Of course, President Trump sold these changes as a means to rebuild the American economy, predicting a massive return of overseas money and increase in domestic investment. As he explained:

For too long, our tax code has incentivized companies to leave our country in search of lower tax rates. My administration rejects the offshoring model, and we have embraced a brand new model. It’s called the American model. We want companies to hire and grow in America, to raise wages for the American workers, and to help rebuild American cities and towns.

The same old story

Not surprisingly, the so-called new American model looks a lot like the old one, with corporations–and their managers and stockholders–gaining at the public expense.

Corporate investment has not been limited by a lack of money. Rather, corporate profits have steadily increased while investment in plant and equipment has remained weak. Instead of investing, corporations have used their surplus to finance dividend payments, stock repurchases, and mergers and acquisitions. Instead of stimulating new productive investment, the tax cut only gave firms more money to use for the same purposes.

The new territorial tax system, which was supposed to promote domestic investment and production, actually continues to encourage the globalization of production since it lowers the taxes corporations have to pay on profits generated outside the country. The new global minimum tax does much the same. Although its supporters claimed that it would ensure that corporations pay some U.S. tax on their foreign profits, as structured it encourages foreign investment. The minimum tax rate remains far below the U.S. domestic rate, and the larger the capital base of the foreign subsidiary, the greater the foreign profits the parent firm can shield from taxation.

As for the one-time tax break on repatriated profits, the fact is that most of the money supposedly held abroad was already in the country, sitting in accounts protected from taxation. Moreover, since firms remain reluctant to invest, the one-time break only served to give firms the opportunity to channel more money into nonproductive uses at a special lower tax rate.

Tax realities

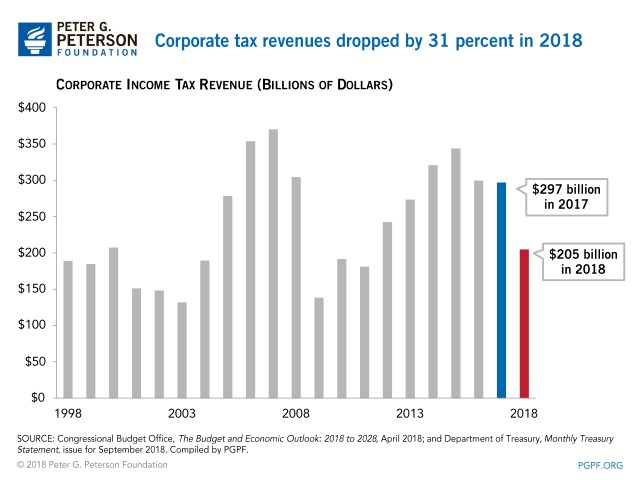

According to the Treasury Department, corporate income tax receipts fell by 31 percent in fiscal year 2018. As a Peter G. Peterson blog post explains:

The 31 percent drop in corporate income tax receipts last year is the second largest since at least 1934, which is the first year for which data are available. Only the 55 percent decline from 2008 to 2009 was larger. While that decrease can be explained by the Great Recession, the drop from 2017 to 2018 can be explained by tax policy decisions.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, enacted in December 2017, is responsible for the plunge in corporate income tax receipts in 2018. Those changes include a reduction in the statutory rate from 35 percent to 21 percent and the expanded ability to immediately deduct the full value of equipment purchases. The Congressional Budget Office points out that about half of the 2018 decline occurred since June, which includes estimated tax payments made by corporations in June and September that reflected the new tax provisions.

Ben Foldy, writing for Bloomberg news, highlights the spoils that went to the banking sector:

Major U.S. banks shaved about $21 billion from their tax bills last year—almost double the IRS’s annual budget—as the industry benefited more than many others from the Republican tax overhaul. . . .

On average, the banks saw their effective tax rates fall below 19 percent from the roughly 28 percent they paid in 2016. And while the breaks set off a gusher of payouts to shareholders, firms cut thousands of jobs and saw their lending growth slow. . . .

Tax savings contributed to a banner year for banks, with the six largest surpassing $120 billion in combined profits for the first time. Dividends and stock buybacks at the 23 [largest] lenders surged by an additional $28 billion from 2017—even more than their tax savings.

The stability and profitability of global corporate networks

U.S. firms also continue to take advantage of overseas tax havens. As Brad Setser, writing in the New York Times, points out:

despite Mr. Trump’s proud rhetoric regarding tax reform . . . there is no wide pattern of companies bringing back jobs or profits from abroad. The global distribution of corporations’ offshore profits—our best measure of their tax avoidance gymnastics—hasn’t budged from the prevailing trend.

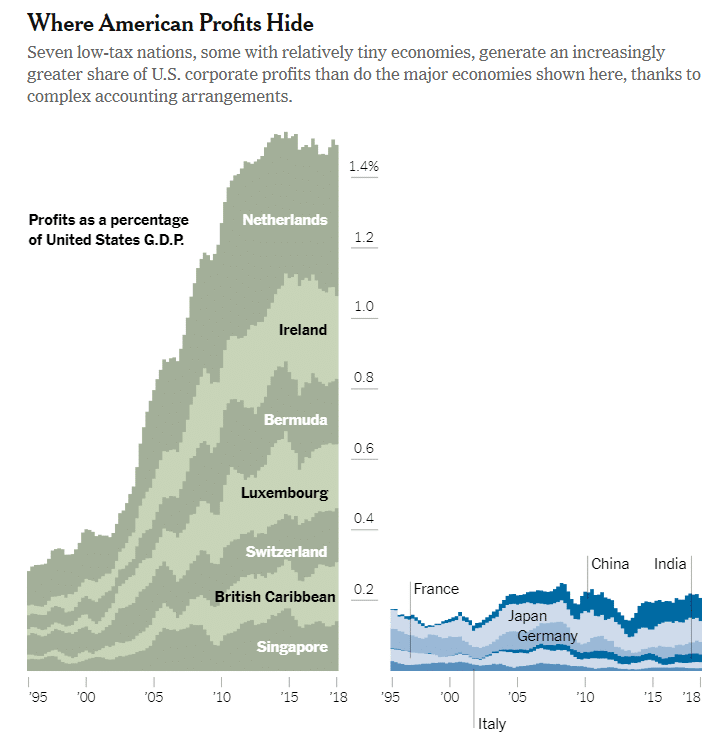

Well over half the profits that American companies report earning abroad are still booked in only a few low-tax nations—places that, of course, are not actually home to the customers, workers and taxpayers facilitating most of their business. A multinational corporation can route its global sales through Ireland, pay royalties to its Dutch subsidiary and then funnel income to its Bermudian subsidiary—taking advantage of Bermuda’s corporate tax rate of zero.

The chart below makes this quite clear, showing that U.S. profits are disproportionately booked in countries where there is little or no actual productive activity.

In fact, as Setser notes, “the new [tax] law encourages firms to move ‘tangible assets’—like factories—offshore.”

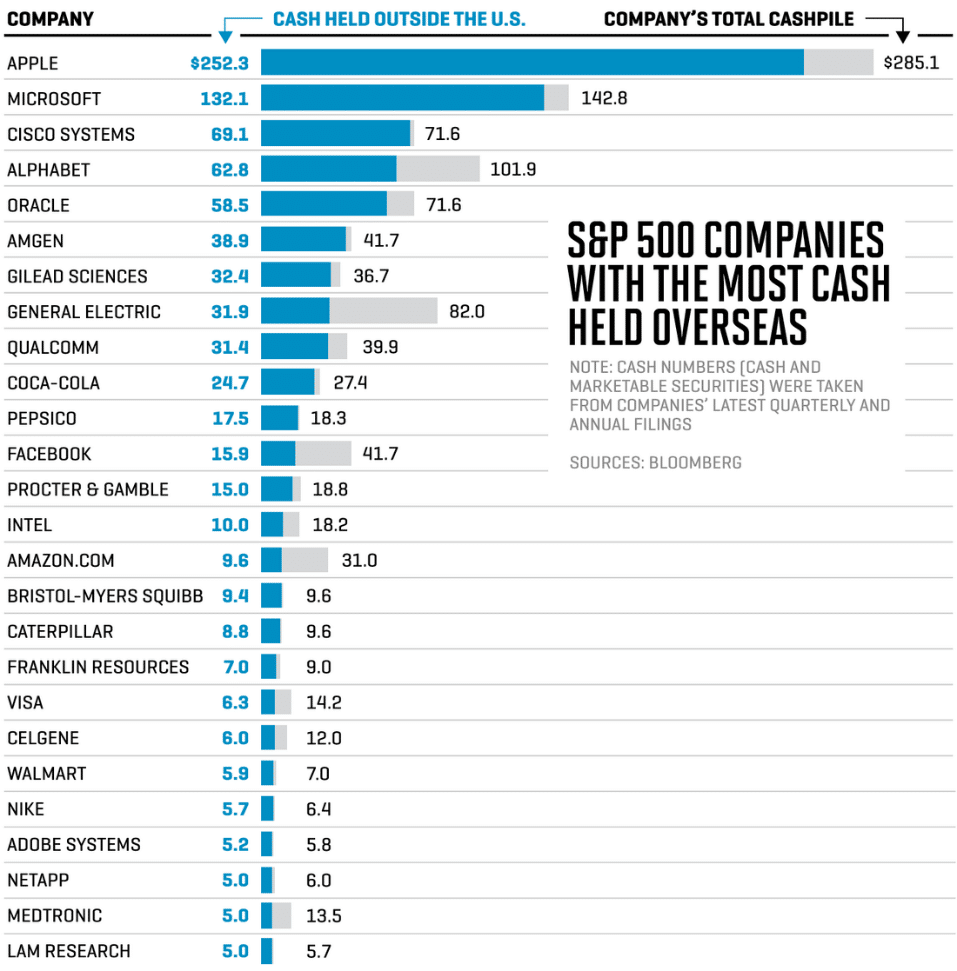

The chart below, from a Fortune magazine post, provides an overview of the large cash holdings of some of America’s largest corporations and the share held “outside” the country.

Economists estimated that U.S. firms held approximately $2.6 trillion outside the country and the Trump administration predicted that a large share would be brought back, funding new productive investments, thanks to the one-time lower tax rate included in the 2017 tax reform act. Government officials and the media talked about this money in a way that gave the impression that it was actually sitting outside the country. But it wasn’t.

Adam Looney, in a Brookings blog post, clarifies that:

”repatriation” is not a geographic concept, but refers to a set of rules defining when corporations have to pay taxes on their earnings. For instance, paying dividends to shareholders triggers a tax bill, but simply bringing the cash to the U.S. does not. Indeed, nearly all of the $2.6 trillion is already invested in the U.S. . . .

U.S. multinational corporations can defer paying tax on profits they earn abroad indefinitely by agreeing not to use the earnings for certain purposes, like paying dividends to shareholders, financing domestic acquisitions, guaranteeing loans, or making investments in physical capital in the U.S. In short, the rules prohibit a company from using pre-tax money in transactions that benefit shareholders. No one believes this is rational or efficient, and it is certainly onerous for shareholders, who would rather have that cash in their pockets than held by the corporation. But those rules don’t place requirements on the geographic location of the cash. Multinational firms are allowed to bring those dollars back to the U.S. and to invest them in our financial system.

Indeed, that’s exactly what they do. Don’t take my word for it, the financial statements of the companies with large stocks of overseas earnings, like Apple, Microsoft, Cisco, Google, Oracle, or Merck describe exactly where their cash is invested. Those statements show most of it is in U.S. treasuries, U.S. agency securities, U.S. mortgage backed securities, or U.S. dollar-denominated corporate notes and bonds.

Of course, these firms could easily have used their tax deferred dollar assets as collateral to borrow to finance any investment projects they found attractive. Their lack of interest in doing so provides additional evidence that low corporate rates of investment are not due to funding constraints. Rather, corporations have only a limited interest in undertaking productive investments in the U.S.

Thus, it should come as no surprise that the one-time tax break resulted in a one-time, modest, “repatriation” and that the money was largely used for financial rather than productive purposes. The New York Times reports that:

JPMorgan Chase analysts estimate that in the first half of 2018, about $270 billion in corporate profits previously held overseas were repatriated to the United States and spent as a result of changes to the tax code. Some 46 percent of that, JPMorgan Chase analysts said, was spent on $124 billion in stock buybacks.

The flow of repatriated corporate cash is just one tributary in what has become a flood of payouts to shareholders, both as buybacks and dividends. Such payouts are expected to hit almost $1.3 trillion this year, up 28 percent from 2017, according to estimates from Goldman Sachs analysts.

In sum, thanks to the Trump tax plan, trillions of dollars that could have been used to transform our transportation and energy infrastructure, industrial structure, and system of social services are instead being transferred to big businesses, who use them for speculative activities and to further enrich their already wealthy managers and stock holders.

Given current realities, we can expect growing popular interest in and support for new public initiatives like the Green New Deal and a new progressive system of taxation to help finance it. Hopefully, exposing the workings of our current tax system and the lies our government and business leaders tell about whose interests it serves, will help speed this development.