The Atlantic (4/17/19) wonders “whether slow suffocation will prove a match for the myriad international actors that have shored up support for Maduro.”

“Trump’s Venezuela Policy: Slow Suffocation,” an Atlantic report (4/17/19) by Uri Friedman and Kathy Gilsinan, passed up a rich opportunity to expose the humanitarian pretexts for economic intervention, and instead exhibited the worst tendencies of corporate media coverage of U.S. policy in Latin America.

The report focused on the Trump administration’s new sanctions on the countries National Security Adviser John Bolton branded as the “troika of tyranny” and “three stooges of socialism”: Venezuela, Cuba and Nicaragua. The administration plans to activate provisions in the 1996 Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity (Libertad) Act to allow U.S. citizens to sue foreign companies “trafficking” in “stolen land.”

While the headline on its own could be read as accurately suggesting that the Trump administration’s policy was one of “slow suffocation” of the Venezuelan people, the subhead makes it clear that the Atlantic was really saying that the aim was “to tighten the noose on Nicolás Maduro”—described in the piece as Venezuela’s “authoritarian” leader. By primarily framing U.S. sanctions against Venezuela as a “diplomatic” alternative to the “military solution,” and as a continuation of a new Cold War contest against Russia, the report continued the corporate media practice (FAIR.org, 2/6/19) of downplaying the real harm sanctions are already inflicting on Venezuelans.

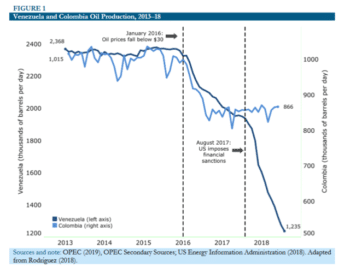

The Center for Economic and Policy Research (2/4/19) has pointed out how recognition of Juan Guaidó as president of Venezuela effectively functions as an oil embargo on Venezuela. This is devastating, since Venezuela’s economy depends almost entirely on oil export revenues for essential imports like food, medicine and medical equipment (New York Times, 2/8/19). Newer U.S. sanctions that have caused Venezuela’s crude oil production to plummet even further are expected to reduce revenues over the coming year by $2.5 billion, almost as much as the country spent last year ($2.6 billion) to import food and medicine (CEPR, 3/25/19).

CEPR (4/19) compared Venezuelan and Colombian oil production to show that while falling oil prices hurt Venezuela’s oil industry, U.S. sanctions hurt far more.

Economists Mark Weisbrot of CEPR and Columbia’s Jeffrey Sachs (CEPR, 4/25/19) have estimated that the death toll from U.S. sanctions is more than 40,000 in 2017–18 alone, based on the experience of other countries in similar situations. They note that sanctions produce lethal effects by increasing unemployment and restricting access to essential imports like food and medicine, as well as preventing easy fixes to problems like rampant hyperinflation (Real News, 1/18/19). This is why UN human rights experts denounce U.S. sanctions as “economic warfare,” which could amount to “crimes against humanity,” and compare the way they kill Venezuelans to a medieval siege (Independent, 1/26/19; Grayzone, 4/7/19).

Although it’s hard to see how one measures the “success” of sanctions—except by their capacity to immiserate the target populations—apparently the only “open question” for the Atlantic is whether or not “gradual economic strangulation” will “prove a match” for the support for Maduro from “foreign patrons” like Russia, China and Cuba. By confining itself to questions of tactical efficacy, and whether sanctions will triumph over the American empire’s rivals, the report completely omits questions of whether or not the U.S. possesses the moral prerogative, and legal authorization, to impose unilateral sanctions and embargoes for regime change purposes.

The authors use the word “diplomatic” to describe sanctions several times throughout the piece, but oddly don’t cite a single diplomatic body to discuss them. If they had asked the UN Human Rights Council, which has condemned “unilateral coercive measures” like U.S. sanctions against Venezuela, they might have noted that they are “contrary to international law.” Or the UN General Assembly, which has declared illegal the US’s ongoing embargo against Cuba for the 27th consecutive year in a recent vote of 189 to 2—with only the U.S. and Israel voting against the resolution. The UN Charter, which grants the UN Security Council alone the legal authority to authorize sanctions and military interventions, or that of the Organization of American States, which forbids economic coercion altogether, would also have been good places to check on unilateral sanctions’ alleged diplomacy.

When discussing the Libertad Act, the Atlantic falsely referred to the revolutionary Cuban government’s nationalization of foreign-owned assets—which had often been given out by the former US-backed Batista dictatorship (CounterPunch, 3/23/16)—as “stolen land.” Legal scholar Marjorie Cohn has pointed out that a sovereign’s nationalization of the property in its jurisdiction doesn’t violate international law (Truthout, 2/24/19), as former U.S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk admitted in 1962:

Any sovereign national has the right to expropriate property, whether owned by foreigners or nationals. In the United States, we refer to this as the power of eminent domain. However, the owner should receive adequate and prompt compensation for his property.

The Atlantic piece also failed to mention that the Trump administration’s activation of Title III of the Libertad Act would also overturn longstanding legal precedent, as the U.S. Supreme Court determined, in 1964’s Banco Nacional de Cuba v. Sabbatino, that U.S. courts shouldn’t decide the legality of taking property in Cuban jurisdiction. The Court held that such questions would be best resolved in state-to-state negotiations—which the U.S. government has refused to engage in, despite the Cuban government’s repeated offers to comply with international law by compensating the nearly 6,000 U.S. parties with outstanding claims, as it successfully did with investors from other countries.

Most importantly, the Atlantic blindly peddled the humanitarian pretext offered by Trump administration officials, that they are merely opposing “tyranny” in Latin America officials. Instead of recalling the US’s history of using sanctions to undermine popular leftist governments to “make the economy scream,” installing reactionary dictatorships in countries like Chile, or supporting a failed 2002 Venezuelan coup to remove the popularly elected President Hugo Chávez (Extra!, 5–6/02), the authors leaned into corporate media tropes about Latin American leftists.

Mimicking Bolton’s red-baiting, the Atlantic characterized the other two nations targeted by him as “repressive socialist governments”: Cuba and Nicaragua, where revolutionaries overthrew the reviled US-backed Batista and Somoza dictatorships in their respective countries (New York Times, 3/16/86). The Atlantic erased Maduro’s numerous domestic supporters, and the pre-sanctions social gains of the Bolivarian revolution (FAIR.org, 2/20/19), by depicting him as an isolated “strongman” propped up by “foreign patrons.”

The “humanitarian” motivation of sanctions and embargoes is also belied by U.S. State Department memoranda that openly strategized to undermine the fledgling Castro government by intentionally driving the population to “hunger” and “desperation.” These half-century-old documents are echoed by recent remarks by Trump administration officials boasting that U.S. sanctions resemble Darth Vader’s death grip, and claiming that Venezuela’s “total economic collapse” is evidence that regime change “is working.”

However, one shouldn’t expect corporate media to provide the kind of illuminating journalism that would expose and contradict official pretexts, because their support for sabotaging popular left-wing political agendas abroad is fully consistent with their practice of discrediting similar agendas at home (FAIR.org, 2/8/19).