Elías Jaua, who as a student participated in the clandestine section of the (then) revolutionary party Bandera Roja, is a Venezuelan politician and former university professor. Chavez appointed him minister of agriculture and vice president, while under Maduro he has been minister of foreign affairs, communes, and education. Jaua is currently a key figure in a Chavista political movement called Encuentro de Lucha Popular and writes regularly, with a firm anti‐imperialist position while defending popular power as the centerpiece of the Chavista project.

You participated in the formation of the movement that, in 1997, would come to be called the Fifth Republic Movement [MVR]. That gives you a privileged perspective on the genesis and formation of Chavismo as a political movement in the 1990s.

I began to work directly with Comandante Hugo Chavez in May 1996. By that time, Chavez was already exploring the idea of participating in elections. The proposal on the table was to give an electoral course to this movement that emerged from the military barracks [in the 1980s] but that beginning in 1994 joined up with all the popular and left currents in the streets of Venezuela. Finally, in 1997, the decision was taken to participate in the 1998 elections with the candidacy of Hugo Chavez.

On April 19, 1997, during a congress of MBR‐200 [a civilian and military movement founded by Chavez in 1982], the movement approved the forming of an electoral instrument that would eventually be called the Fifth Republic Movement (MVR). The driving idea was that the Bolivarian project was aiming to re-found the republic. Up to that point, there had been four republics in the history of Venezuela. The MVR proposed to make a hard rupture with that history by creating a Fifth Republic.

Around that time, Chavez put us to work–the people who had been close to him–developing what we called the Patriotic Circles [Círculos patrióticos] which were organizational structures of a minimum of five people in each barrio, in each community, in each town. These [were the first steps toward] the electoral structure that would allow us to go on to the 1998 campaign and the December 6, 1998 elections.

Around that time, the work that had begun in 1996, began to pick up speed with Chavez’s tour around the country. Really, he went everywhere! I belonged to a team that went on preparing the events in which Chavez was to meet with the people, which generally were in public squares, since other institutional spaces were not given to us. We prepared meetings with local groups and generated, with the local leaders, the conditions for public gatherings. As we did this, we also worked with the folks who, at a local level, were building the Patriotic Circles.

That was in 1997. Then, in 1998, I was given the task of building the political structure and direction of the movement in the state of Miranda [the country’s second most populous state that includes east Caracas]. By then there were some twenty-five thousand Patriotic Circles, and it was necessary to begin organizing the work we had done. That is when we formed the “Tactical Regional Commands” within the MVR initiative, and I was given the task, with a group of comrades, of working in Miranda and organizing the forces there. However, I continued to accompany Comandante Chavez throughout the campaign.

How would you characterize the class composition of the movement in those early days?

It was multiclassist, and it had an ideological diversity that went from the radical left to sectors of the right. I refer to members of the old bourgeoisie that were against the two major parties, AD and COPEI*, but who were nevertheless extremely conservative. Even through 1996, there were even some extreme right groups or individuals who participated, but they pulled out rather rapidly. Obviously, the movement was also composed of popular forces, the popular movement, left organizations, and patriotic sectors of the military. So, to sum up, the movement as a whole had a muliclassist origin.

How did the movement deal with such great diversity?

The fact that in the beginning the movement was multiclassist and ideologically diverse made it quite sturdy in a way that was needed at the time. Chavez insisted on the recognition of plurality. He was always a “factor” that generated equilibrium in the movement, focusing on the consensus which was that we had to [take power] and re-found the republic.

Obviously, the debates were very intense, but there was, however, a desire on the part of all of us who participated in the movement (and in the whole of society) to bring closure to the bipartisan Puntofijista model of government[*]. What unified us was the goal of putting Hugo Chavez in the presidency on December 6, 1998.

However, the multiclassist character of the movement in its early days is the reason why there were many fractures during the first years of Chavez’s presidency. What unified us early on was the goal of ousting AD and COPEI, but later, as Chavez pushed the revolution in a more popular direction, that is when right‐wing sectors began to separate from the movement.

For Chavez, refounding the state and the creation of the new republic had much to do with a radically new concept of democracy that is already present in The Blue Book [short book written in 1992 by Hugo Chavez, in which he presents his views on history and democracy]. I think we could say that that conception of democracy, as expressed in that early document, already points to the socialist project that would later develop in the Chavista movement.

How do you see the relationship between democracy and socialism in Chávez?

Let’s address the question non‐chronologically. Chavez, around 2010 and 2011 began to affirm in many public addresses that “democracy is socialism, and socialism is democracy,” and he said that “capitalism is anti‐democratic by nature.” In other words, he broke with the false dichotomy that separates democracy and socialism.

Later, Chavez went on to say that we shouldn’t be talking about “democratic socialism,” because socialism is, in essence, democratic. Instead, he claimed that we should talk (and think) about socialist democracy. So there, in a few words, President Chavez answers your question.

No doubt, the issue of democracy, of demos kratia or people’s power, is a vein that runs throughout his thinking. It’s there in The Blue Book, and it’s there in the Alternative Bolivarian Agenda [Agenda Alternativa Bolivariana of 1996]. Chavez made philosophy and culture out of this reflection on democracy and popular power. The right of the people to speak, participate, propose, express themselves, and, of course, decide–all that was key to his thinking and his practice.

Chavez was committed to popular sovereignty, and he also understood that the leader was obliged to do what people said. Because of that, from the right and even from certain intellectual sectors of the left, there emerged a discourse that satanized Chavez. They said, “Chavez didn’t seal agreements, he didn’t make any compromises with other sectors of society, and he didn’t address minority rights.” But for Chavez democracy was the mandate of the majority and the recognition of the minority. There was recognition, but there was no pact to be made when the majority spoke loud and clear.

Additionally, Chavez was always very honest with the people regarding his electoral proposals. Thus, in the 1998 campaign, he clearly called for a constituent process. After the victory, however, powerful economic and political sectors went to him and said that there had to be an agreement before going through the constitutive process. To that he said, “No, I have a mandate.”

Thus, in every electoral process, he made an explicit public proposal. Later, when the people voted for him, the proposal became a mandate. Another such instance was in 2006, when he declared socialism to be his electoral project. From then on, he appealed to the mandate that the people had given him to justify going forward.

These are some windows into how Chavez brought the question of popular sovereignty into the spaces of representation, into the framework of classical liberal democracy. However, as you know, direct democracy was also important to his project.

Chavez promoted and fostered direct democracy and opened the doors for the construction of popular power so that the people would have real power, effective power… That is where the communal councils come in, and the campesino councils, student councils, worker councils, and communes. It all began with the Patriotic Circles, that were already a sort of expression of direct democracy.

In the crisis-ridden decade of the 1990s, the movement that grew around Hugo Chavez pursued the ethical reorganization of politics and society. Obviously, we are facing a crisis of the Bolivarian Process, and you have mentioned that to overcomethe current situation a new “historical trigger” [detonante histórico] is needed: something akin to what happened on February 4, 1992 [Chavez’s military insurrection] or Chavez’s election in 1998.

The movement that Chavez led in the 1990s–he said so himself in many occasions–was based on the aspirations of Venezuelan society as a whole. [People wanted] an independent and sovereign country as opposed to being subordinated to the United States’ geopolitical interests and the auctioning of our wealth to that country. [People also wanted] a country with less inequality, with less poverty, and a more honest country. That is how Chavez summed up what were the goals and desires of the society. One could even say that he incarnated that collective desire.

Within the society, there was a sense that something had to happen so that a new epoch could open up for Venezuela. And that indeed happened. The year 1998 [with Chavez’s election to the presidency] marks a pacific and democratic rupture; it was a historical trigger and a break with the old, corrupt political model. But it also brought a series of emergencies and aggressions led by conservative sectors of the society. The years 2002 [with the coup d’etat and oil sabotage], 2004 [when the opposition tried to revoke Chavez as president], and 2007 [which brought violent right‐wing student mobilizations] were periods of intense desestabilizacion.

Without a doubt, 1998 marks the beginning of the period of greatest independence and sovereignty that Venezuela has had in its history. It is also the period of greatest democratization–not only in political terms, but also in economic, cultural and social terms. From the presidency and from the government, a new ethical logic emerged in the public eye. It was something that Venezuela hadn’t seen before. For the first time in a long time, Venezuela had a president that was an example for the society, someone to emulate. His life corresponded with his principles. I say this because ethics doesn’t only refer to the administrative arena. We are also talking about political ethics and a political identity: a coherence in discourse and practice.

Unfortunately, that logic didn’t become a culture penetrating the entire state apparatus and the society as a whole.

Hugo Chavez wasn’t just honest in the way he administered things. He was first and foremost a politically honest person. As I said earlier in the interview, he never deceived people about where he was going. He always said, “Whoever votes for me is voting for this project.”

In our time, obviously all those hopes and desires that were realized [under Chavez] are, in some way, very precarious. National independence is now under threat, as we face the possibility of a military intervention, while the sanctions limit our capacity to manage our own resources and finances. On top of this, our capacity to represent ourselves abroad is also being curtailed. All that undermines our national sovereignty.

This new phase of the confrontation–which goes hand in hand with other political shifts–began with a sector of the opposition not recognizing Nicolas Maduro’s 2013 presidential election. That began to have an impact on our economy, and inequality began to grow. We are in a country where poverty is a serious problem again, where hunger has reemerged, where difficulties to access healthcare and education are real, quotidian problems. No doubt there are several factors here, such as the fall of oil prices and the emergence of new political mechanisms, but the main factor is the prolonged political confrontation.

Today we are, once again, an unequal society after having reverted the bad karma of being the country with the largest income in Latin America, but also the country with the most inequality. With Chavez, Venezuela became the country with the most equitable income distribution. Today, I don’t know where we stand in the charts, but it’s enough to look at the streets to see that we are in a terribly unequal society. There are sectors that accumulate, generally through illegal means, a great deal of wealth, while the people are watching their rights vanish and their living conditions rapidly deteriorate.

Furthermore, the institutional instability provoked by this long confrontation has made it so that corruption has metastasized throughout the whole social body.

So now we are facing the same dilemmas that Venezuelan society faced in the 1990s, with one difference: today we have a project and we demonstrated that it is possible to contain society’s scourges, and most of all, we have a pueblo that is organized, has a high degree of consciousness and is committed to reprising the path that Chavez initiated. We are facing a very difficult situation, but I believe that it’s possible to begin an ethical refounding of the country. That has to take place in the economical, political and social spheres.

The Chavista movement is firmly unified when facing imperialism. However internally, as is to be expected, there are different tendencies and diverse proposals regarding the solution to the current crisis. Some people claim that the solution is foreign investment and privatizing public enterprises. Others argue that we should look to a communal solution and point to such initiatives such as El Maizal Commune or the Pueblo a Pueblo plan. What do you think?

The multiplicity of interpretations to which you refer has its roots in the policlassist character of the Chavista movement. It is a sum of currents from diverse ideological and political origins, each with different life practices. That means that there will always be tensions.

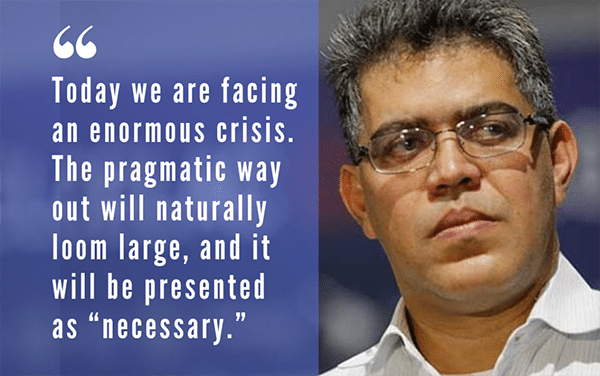

Today we are facing an enormous crisis. The pragmatic way out will naturally loom large, and it will be presented as “necessary,” even it that means flexibilizing principles that are at the core of the Chavista movement.

Here, we should say that the Bolivarian model has never ever proposed eliminating private property and private investment. That wasn’t the case in the Alternative Bolivarian Agenda or in the Plan de la Patria [2012]. The Bolivarian Revolution is a mixed model in which the state has a key role [at the commanding heights] of the economy, with a private sector that is to be subordinated to the interests of the people, and with the emergence of a sector that was initially called “social economy,” but which later became known as “communal economy.” That is the first thing that should be made clear.

Additionally, when we talk about the weight of these sectors in the economy, it should be observed that Chavez’s main objective was to foster the emergence of an economy in the hands of the people and not in the hands of capital. He was keen to not repeat the error of European socialisms, which was statism, but on the other hand he turned away from any glorification of private property. Briefly put, Chavez’s conception broke with the hegemony of private capital.

Today, there are longstanding currents–those that say that the objective of the Bolivarian Revolution was [merely] to displace the old regime (which it did), and claim that guaranteeing public education and access to healthcare was, in itself, the goal–which are becoming more visible. Their discourse turns around the idea: “socialism in the social.”

Hugo Chavez always combatted the “socialism in the social” premise. When he declared the socialist character of the revolution, he made it crystal clear. He said: “I’m not talking about western European socialism; it’s not just about resolving some social problems through the state’s participation.” That is why striving for a society where the hegemony of the economy is in the private sector is contrary to the spirit of this revolution.

The reasons adduced by the privatizing tendency are absolutely flawed. They talk about the inefficiency of state property and social property. However, the bulk of the process of nationalization happened between the years 2007 and 2008, and those are the years with the biggest GDP growth, not only in the oil sector, but also in industrial and agrarian sectors. CEPAL numbers prove it.

The interesting thing is that the state enterprises doubled or even tripled their production in those years. This is in part because the state injected resources, which private capital wasn’t willing to do. However, it was also because the whole process of nationalization inspired a collective spirit of commitment. All this meant that food production grew exponentially, while poverty was practically eradicated.

What’s more, without nationalizing the steel and cement industries, which had been in the hands of transnationals, the Great Venezuelan Housing Mission [governmental housing initiative] wouldn’t have been possible. Without a nationalized CANTV [telephone company], the democratizing of communications wouldn’t have happened, because people wouldn’t have been able to pay for the services. This is important because we shouldn’t see things exclusively from the standpoint of economic profitability. The social results of the nationalizing process also need to be taken into account.

Chavismo’s collective will–and I have seen it the assemblies and meetings that I attend regularly–is opposed to letting the private sector rule. We don’t deny that it can participate in the economy, but we don’t place our bets on the private. Those of us who defend the revolutionary project and remain committed to it, we cast our lot with the people. Can anybody in their right mind think that the private sector can save us right now, the very sector that failed to develop our economy for decades and decades?