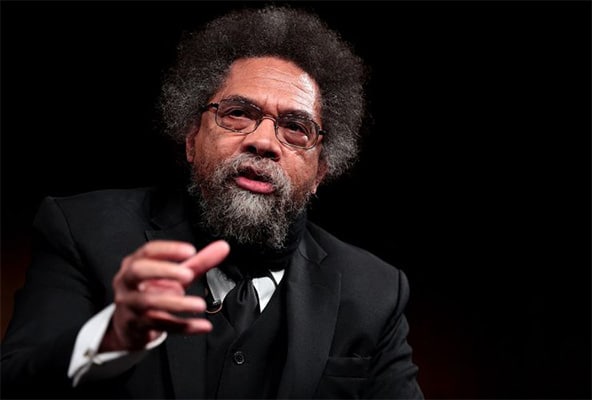

Boston Review editor Deborah Chasman first met Cornel West in 1992 when they worked together to publish his best-selling book, Race Matters (1993), with Beacon Press, a year after the Los Angeles rebellion. At the time a professor of religion and philosophy at Princeton, West had already published eight books, but now found himself at the center of national discussions about race—a role he has occupied ever since.

Chasman and West sat down earlier this month for a conversation about that experience, the disproportionately white publishing world, the responsibilities and burdens of public life, and the predicament of black intellectuals today.

Deborah Chasman: Let’s just start twenty-six years ago when we worked together on this book, Race Matters.

Cornel West: Yeah, I was blessed to work with you. You showed up at my office at Princeton and asked whether I had anything. I said no, I don’t really think I have anything at all, and you looked around the floor and you saw these essays [laughing] and said, well, what is this? What is this? What is this? I said, oh yeah, that was—that was in Prospect, The American Prospect, that was in Dissent and Irving Howe had asked me to write, this was in Praxis International where Seyla Benhabib had asked for me to write. Lo and behold, we had about nine or ten, and I end up writing just one new fresh essay on black sexuality and—

DC: That was it; it launched you. Do you feel that way?

CW: Oh absolutely. And I think it was about my ninth book, but it catapulted me. I had books on American pragmatism—Prophesy Deliverance! (1982), Prophetic Fragments (1988), The American Evasion of Philosophy (1989)—and then Breaking Bread (1991) with bell hooks, The Ethical Dimensions of Marxist Thought (1991), the two volumes entitled Beyond Eurocentrism and Multiculturalism (1993), as well as Keeping Faith (1993). But Race Matters just took off. I would not have the kind of visibility if it hadn’t been for your wise judgment [both laugh], to see those pieces around, and say, I think we got a book here.

DC: What was the experience like for you? Did it take any turns that you didn’t expect or that were hard to navigate?

CW: Well, one of the surprising things was that on my lecture tour I was followed in a very critical way by my brothers in the Nation of Islam. I had the chapter on Black-Jewish relations, and I had been critical of my dear brother Minister Louis Farrakhan. I would say, come sit in the front row. I’ll give my reflection and then we’ll have a dialogue on why I used the kind of language that I did about Minister Louis Farrakhan. For three or four stops, they were always there, deeply upset.

DC: I didn’t realize that.

CW: Oh yeah, absolutely. I ended up having a meeting that went on for nine hours with Minister Farrakhan on what we mean by anti-Semitism, anti-Jewish hatred, what kind of language I viewed as anti-Semitic—Farrakhan’s talking about Jews or the Jews as opposed to the conservative Jews or the right-wing Jews or the liberal Jews or the radical Jews. We had a rich dialogue; we went back to the biblical texts and had a long discussion on the book of John.

He said look, brother West, John said “the Jews.” I said I know, I said that that’s an anti-Jewish element in the biblical text—written by a Jew. We had long discussions, and we learned from each other. We really did. I heard him speak about a year or so later. He now was talking about particular Jews rather than the Jews as a whole—now sometimes, he swings back and forth, but it was interesting that he seemed to take it in. Then we had a discussion about patriarchy. I had said he was too patriarchal, and he said, oh, we just appointed a woman in a high place in a mosque. I said that’s nice tokenism, but we’re talking about something that’s more structural and more theologically and ideologically deeper. Patriarchy is shot through my own Christian tradition, and your own Islamic tradition. Those conversations were probably the first challenge to my new public status.

Ben Chavis and Minister Farrakhan and myself went around the country organizing for the Million Man March. It was very controversial. A lot of my leftist friends thought that the march was not a leftist march, was not a progressive march—it was too patriarchal, too tied to the Nation of Islam. Towering figures like Michael Walzer and Adolph Reed put forward strong critiques of the march and me. I said, we’ve got to have a variety of voices there.

DC: When the book came out, you became a public intellectual, and you were in a position to talk to black communities as well as large white audiences who came out to hear you. Was your approach different, depending on your audience?

CW: I had an internal thing with the black community, with the churches and the Nation of Islam and the left black critics; then I had the larger white mainstream which is for the most part liberal, neoliberal.

It was fascinating. I always try to be consistent. I was invited to a lot of liberal gatherings. The text lent itself to a much easier liberal reception than my own actual politics.

DC: I wondered whether the white audiences really understood what you were saying.

CW: That’s so true. Good God almighty, it was like I was one of the liberal establishment, I said no, no, you’ve got the wrong negro for that. But the text lent itself to that kind of appropriation.

DC: Why do you think that is? I’ll take part responsibility for it—

CW: Oh no, it’s a positive thing, because it’s got a lot of different elements. It’s a heterogeneous text with a variety of the essays. For example, the most popular essay in the book was the nihilism essay—

DC: We put it first.

CW: For good reason.

DC: But it was so harshly criticized—

CW: Oh my God it was hit hard because, people said I was giving too much to the right in terms of personal responsibility and individual culpability. But I was still talking about structural and the institutional conditions, so the right-wing folks said, well he’s still not one of us, he can’t have it both ways, he’s looking for the middle road. I wasn’t looking for the middle road. I was looking for what is beneath the superficial discourse. There’s a difference between movement to the middle and movement beneath a discourse that’s too much on the surface. So when I talked about commodification as tied to nihilism, that really comes out of Lukács, it comes out of the Frankfurt School, it’s a Marxist formulation, it comes out of the first volume of Capital.

But it wasn’t read that way. People accused me of saying that black nihilism is primarily a cultural and personal crisis rather than a structural institutional crisis. I said no, no that’s not what I’m saying. I’m saying the structural sources are what drive so much of the cultural and individual effects.

DC: I was amazed and thrilled that the book was so successful, but the success also terrified me.

CW: In which way?

DC: The extent to which I could not anticipate how the book would be received and read and understood and did not think more in advance about what role I—or Beacon Press—may have had in how the world received it.

I have a story that I’ve never told you. When the manuscript was finished and we were almost ready to go to press, Wendy Strothman—my boss, head of Beacon Press—read it. She was excited; she was a great publisher and she knew it could be a big book for us. And she said, I think it needs a preface, something a little more personal to help the reader get into it. And I didn’t want to ask you for anything else at that point. And I said, okay—she was my boss—what did you have in mind? And she said, maybe you could tell a story about not being able to get a taxi. And I had this deer-in-the-headlights moment: I didn’t think that was the right personal story to represent the book, but I was afraid to tell her that. I was afraid to tell you too, but I thought I’d just pass along the suggestion, and you’d say what you wanted.

CW: Wow. . . . In her own mind she already had the notion of not being able to catch a taxi. It just so happened that that was the case when I was just trying to take the picture for the cover of the book. Isn’t that something?

DC: Right. It had just happened to you. Meanwhile I was thinking you’d be annoyed at the suggestion—after all, you were talking about the crushing nature of structural racism. And then you wrote about the taxi, and have been criticized for it ever since.

CW: It’s interesting how the taxi story took off. For me, the more interesting moment in the preface is when I’m driving up to teach at Williams College and am pulled over by the police. I’m accused of being a cocaine dealer and taken to jail. Very few people talked about it. And I’m thinking, in terms of my life, that’s much more significant than the taxi incident. Why do you think people talk about one as opposed to the other?

DC: I think this is partly Michael Denzel Smith’s point in his recent Harper’s essayabout black intellectuals and mainstream publishing: when the assumption is that you’re being read by a white audience, certain kinds of stories resonate. So the pull of mainstream publishing put black intellectuals in a bind.

CW: It’s interesting. I was just teaching George Schuyler and LeRoi Jones’s Blues People (1963), and Jones writes, “The Negro American had always sought to adapt himself to the other America and to exist as a casual product of his adaptation, but this central concept of Afro-American culture was discarded by the middle class. After the move north and the sophistication that that provided, it was assimilation the middle class desired: not only to disappear within the confines of a completely white America but to erase forever any aspect of a black America that had ever existed.” And then for him it’s really in the music where the strength, the beauty comes out of the depth of black people’s soul. It’s tied to the lower class’s persistent calls to hold onto the best and not to be diluted by the mainstream. That’s part of the predicament of certain black intellectuals.

I call myself a blues man in the life of the mind and a jazz man in the world of ideas. Certain musicians set the whole tone and vocation for me. When you talk about John Coltrane and Sarah Vaughan, they’re not worried about just a white audience or just a black audience. They know their audience is out there—they had to deal with market realities—but they have a sense of calling and vocation that goes far deeper and beyond any preoccupation with writing letters to the Philistines, as it were, translating black culture to a larger white audience. You’re speaking the truth from the depths of your soul. Everyone can come and get it. If you don’t, you are the one missing out on something rich.

Sarah Vaughan not singing just for black and white. She’s not going to just sing “Send in the Clowns” by the great Stephen Sondheim just for the white folk or just for the black folk. She’s singing from the depths of her soul—this is what she’s feeling. Coltrane is the same way. He’s going to blow up “My Favorite Thing,” not for the Rodgers and Hammerstein crowd. He’s doing Coltrane himself, no matter what. For me, these are the great exemplars. And it’s very difficult to do that as a black intellectual of the word, spoken or written.

DC: You say what you want, but it might come with a cost. Have you had that experience?

CW: Oh indeed, indeed. Especially my critiques of Obama, or my critiques of Israeli occupation, or my critiques of homophobia and transphobia within the black community, all of these things are not that popular.

DC: Baldwin struggled to navigate similar issues.

CW: Yeah, absolutely. Absolutely. But Baldwin is very different than my case—it took more courage on his part because he had no institutional affiliation, no money flow. I always had a job to fall back on, so I could enact my vocation within the confines of those institutions. Baldwin was just out there on his own, an independent writer. Even though he did very well, if he didn’t finish his text, he and a lot of his friends and family were not going to eat. I know he made some money lecturing too, but it’s a very different situation. That’s what I loved about Baldwin, something that I am inspired by about Baldwin, Amiri Baraka, Ishmael Reed, Gwendolyn Brooks—they were all darlings of the liberal establishment, and they rejected that status, which meant they were pushed to the margins.

Ishmael Reed did it, Baraka did it, when he went black nationalist and Marxist. Baldwin did it. His No Name in the Street(1972) is a different Baldwin than Notes of a Native Son (1955). People often said, “Oh, how did he get so radical, he’s talking about socialism, even Trotsky gets a positive mention.” Yeah, that’s Baldwin after he’s been radicalized by the death of Malcolm and Medgar Evans and Martin and so forth. He’s connected with the Black Panther Party, Angela Davis is his sister, sweet Lorraine Hansberry is too. His open letter to Angela, a communist black sister, was not going to make him popular.

But No Name in the Street, that’s the same Baldwin, but much more radical. It’s the connection not just with left politics but the kind of indictments of the structural and the everyday realities of the American empire come through so strong in that text. And that’s part of the story about the early Baldwin who was so wonderful, and the later Baldwin who was so angry and so bitter—but still wonderful. Now of course the greatest example of this is W. E. B Du Bois. He was a darling of the liberal establishment in the early part of the twentieth century. The president sends him to Liberia to represent the U.S. government. He’s going to end up in Ghana, persecuted by the U.S. government, passport taken away in the ’50s. He and Paul Robeson were basically under house arrest.

DC: And what were their transgressions?

CW: Being too close to the Soviets, being cast as communists, being willing to say positive things about the role of the Soviet Union in the decolonization of Africa during the Cold War. The liberal establishment just lined up some middle-class negroes to condemn Robeson, to condemn Du Bois, indict them from the vantage point of NAACP politics; the very organization Du Bois helped found ends up turning against him in that way. So Du Bois and Robeson are the two grandest examples. Robeson is the most popular negro in the whole world in 1939, and then he’s under house arrest on Walnut Street, in Philadelphia, his sister’s house, in the 1950s. When he dies in ’76, most people didn’t even know he was still alive. He was a giant, he was a genius. But the establishment—once it rejects you, there’s no going back.

DC: With Robeson and Du Bois, it was okay if they spoke out about racism, but their critique of the state did them in.

CW: That’s right. And the empire. It’s a critique of empire, critique of capitalism, critique of the policies of the U.S. nation state. Then they come at you. They come at you with their black supporters, you know, very much so.

DC: And with Gwendolyn Brooks, she exited on her own?

CW: Hers was voluntary. She went to a conference at Fisk University and met my dear brother, the towering figure Haki Madhubuti, poet and publisher of Third World Press for more than fifty years. Brooks said, my God, what you’re doing is so rich and deep, and I need to become a part of it. She was the most promising young poet in America, winning the 1950 Pulitzer Prize for poetry, with Henry Seidel Canby, Alfred Kreymborg, and Louis Untermeyer on the committee—white mainstream through and through. She said no, I’m going with these black folk, and she was faithful unto death.

DC: She gave up a lot—

CW: A lot of money, a lot of status, attention, and what have you. But that liberal establishment—they can chew you up and spit you out so quick. Real fast, real fast. So many brothers and sisters in publishing are white; it’s disproportionately white, but not exclusively, because the liberal establishment is a colorful thing these days. But, deep down, so many of them don’t have a profound respect for poor people and everyday people. Brothers and sisters on the block and prisons and so forth. So there’s a class condescension and there’s an arrogance that’s built into that liberal establishment. The folk who get pushed to the margins are not just targeted as individuals, but individuals who are fundamentally concerned, tied in solidarity, focused on the humanity of those poor and working folk. So that rejection has an ideological and a political gravity.

DC: That was at the center of your feud with Ta-Nehisi Coates.

CW: Absolutely.

DC: Should I call it a feud? It’s really a disagreement, right?

CW: Well it began as a disagreement, but it became a feud when there was an attack on my integrity, telling people, well I’ve never read his text, therefore I’m criticizing something that I’ve never read. That was ridiculous. We have different readings of what’s in the text—that’s a separate thing. In internet culture, any critique is a putdown, any critique is a slam or trashing. I was acknowledging the degree to which his voice was one we need to take seriously. But you also have to acknowledge the quality of the claims being made. If he writes that Barack Obama is a culmination of the legacy of Malcolm X, those who love Malcolm have to raise their voices. You can’t mislead a younger generation like that. If you’re going to be the popular figure that you are, then you’ve got responsibilities. You’ve got to talk about capitalism, you’ve got to talk about empire and so forth. You can’t just give a critique of the New Deal and think you’re doing something radical. I mean, Ira Katznelson and others did that many, many years ago. So that’s what it was, but unfortunately, these things degenerate. Same is true with me and brother Dyson.

DC: But I always think about the editor’s role in these things. With Michael Eric Dyson’s huge New Republic piecetrashing you, all I could think of was that some editor said—go ahead, do that one, and won’t this spectacle be fun. You know, take two prominent black intellectuals and let them just fight it out. There was a person sitting there, who said that’s a good idea.

CW: They got high visibility. Leon Wieseltier already tried to trash me in ’95. Dyson’s piece is just another trashing in that same tradition. But because the Israeli policy meant so much to them under Martin Peretz’s editorship, if they see somebody who’s critical of it, then they’ve got one motivation among a whole host of others to say it would be nice to trash this brother so that his legitimacy and authority is called into question. Because he’s leading people down the wrong way in regard to Israel. I used to talk with Christopher Hitchens in Edward Said’s living room, and every time Hitchens talked about New Republic, he called it the pro-apartheid journal. And I said, hey, that’s a little harsh, man, the occupation certainly looks like apartheid, but Israeli Palestinians do vote and have rights. “Well, okay, you can get technical about it, but generally speaking, they’re not going to allow for any serious discussion on Israeli occupation no matter what.” And that’s Hitchens back in the early ’80s.

And now there are the black college tours sponsored by the Philos Project, funded by the pro-Trump and pro-Netanyahu philanthropist, Paul Singer, calling for loyalty pledge of black college students in support of the state of Israel, with keynote speakers such as Dyson.

DC: Were there other issues that you’ve felt shut doors, at least temporarily?

CW: The big one would be brother Barack Obama.

DC: Over the inauguration?

CW: Right. I fought to get my own tickets for the inauguration, I couldn’t get them, and I just thought that was disrespectful of him and his operation. I’m out there breaking my neck for nothing much with all these events, for free—I was not paid one penny. All I want is a ticket for my mother. So I mention this in my dialogue with Chris Hedges, and a lot of people say, West wanted Obama to kiss his ring, and he’s upset that somebody else got tickets and he didn’t. And I just said in the interview that if anybody had done 65 events for free beginning with Iowa, they should get at least a ticket for their mother. My mother grew up in Jim Crow Texas. Having a black president meant a lot to her. By the time brother Obama won, I was not that impressed anyway. I was so glad that we have this symbolic indictment of white supremacy but already knew that he’s made these moves with Wall Street and the Pentagon.

Once he connected with Larry Summers, and Tim Geithner, and Robert Rubin, and when he held Brennan from the Bush administration as tied to the very ugly policies of counterterrorism coming out of the State Department and the Pentagon, I said wait a minute, the war crimes will continue. We’ve been fighting against the drones under Bush. We called Bush a war criminal, for forty-five drones and they killed some innocent folk. And Obama ends up with 547—we don’t know how many really—and you know they’re killing innocent folks. Well those are war crimes too. To say that was to pit yourself against 98 percent of the black community. You know, our hero can’t be a war criminal. They said, “come on, brother West, you’ve really gone too far. You call him a black mascot of Wall Street, that was crazy. Nope, he’s been fighting Wall Street.” I say, what are y’all talking about? What evidence you got? How many Wall Street executives went to jail? And so forth. You’ve got folks wrapped in all of these different lies to protect them. That was true for Dyson, it was true for Sharpton, it was true for most of the black intellectuals of the day. And then the ones who ended up having their careers launched, including Coates himself. There is no Coates without Obama. And that’s not to put Coates down, I think his voice is great. Same is true with sister Melissa Harris-Perry, when she and I got in our fight. There is no Harris-Perry TV show without Obama. And her show was like state propaganda. It was a liberal version of Fox News. There was not a critical word to be said about Obama. MSNBC is all upset now because Fox is just Trump propaganda. I said that’s true, that’s ridiculous, but MSNBC was Obama propaganda. And you have to be consistent and critical across the board of these different neoliberal or conservative versions of capitalist hegemony. You bring that up today and they say, oh you’re just Obama-hating still. No, I’m telling the truth. Evidence just doesn’t mean anything.

DC: So where are the spaces now where truth-telling is possible?

CW: You create your own, you know. Take Yvette Carnell. That strong sister is consistent in so many ways. Very courageous too. I don’t agree with some aspects of her, but I have great respect for her. She’s had her blog for year after year after year. She’s got a following, and she’s always concerned about black working people, black poor people. I proceed based on the primacy of the moral and the spiritual tie to systemic social analysis. And so I connect to people who are fundamentally focusing on poor people and working people. That’s why I love Adolph Reed’s work, I think he is one of the towering intellectuals alive. And he’s come at me tooth and nail for years.

DC: Yes, I remember.

CW: He and I worked together on Bernie Sanders’s campaign. I just talked to him a couple of days ago because we’re coming back together. He’s always got his fundamental concern with working people, poor people, and working black people, and poor black people. And then brings in a very sophisticated Marxist analysis. That’s crucial for me and my own moral and spiritual witness.

bell hooks is an interesting example in this regard, because I think bell in many ways deserves more attention. I saw the New York Times did a piece about how her books had changed people’s lives—past tense. I said no, bell is still alive, I was just with her, we did a new edition of Breaking Bread with a whole new chapter. She’s so important. There’s a bell hooks Institute for critical thought and meditation at Berea College in Kentucky. She’s there because she went back home to take care of her mother.

I think of folks like Haki Madhubuti, who I’ve already mentioned. He deserves much more attention. I’ve got a recent book with him and Father Michael Pfleger. He’s the great, prophetic pastor of Saint Sabina Church, the largest black prophetic church in Chicago. He’s a white brother, he’s my dear brother. The three of us sat down and had a dialogue and we published a text called Keeping Peace, and it’s a tribute to the fifty years of Third World Press being not just in service to black people and oppressed people, but just staying alive and making available so many works. It’s hard to see how Haki does it.

Maulana Karenga is finishing his big book on Malcolm X, which will probably be the best thing written on him. I wrote an introduction to it. And he’s been working on this book for over a decade. He’s going at it, he writes every week in the Los Angeles Sentinel. He’s like the black left version of George Schuyler, because his work is read all over southern California, because it’s a newspaper. A black newspaper. He’s written hundreds and hundreds of columns. Manning Marable used to write for newspapers too. A hundred and ten different newspapers all around the country, and the West Indies and England, in addition to his scholarship.

DC: How do you think the media needs to change?

CW: You’ve got to have either independent black journals or open up the mainstream more to black intellectuals. Take a journal like New York Review of Books. How many reviews by black authors do they really have? It’s almost apartheid-like. You’ve got brother Darryl Pinckney, and I love him, he does wonderful work. You’ve got brother Anthony Appiah. And I love him. He’s like family to me, though we may not always agree. But other than Anthony and Darryl, and most recently the brilliant Zadie Smith, the journal has little else on black intellectual life. And that’s been true for over fifty years.

DC: Change is slow in publishing.

CW: Dear God. But even Times Literary Supplement is so relatively negligent when it comes to high quality black intellectual voices. They got a few—sister Ladee Hubbard and others—but not that many. And so you either go independent or you just have your own little networks that don’t become visible, and you miss out on a lot of important voices.

Farah Jasmine Griffin, Imani Perry, Eddie Glaude. All of them deserve a whole lot of serious attention, wrestling with what they write about. Imani’s book about Lorraine Hansberry is a gift to the life of the mind. A powerful text. Eddie’s book, Democracy in Black (2016), is very important.

DC: Which of your books do you feel was the most important?

CW: I think the most exciting was probably my first book, Prophesy Deliverance!, with Westminster John Knox Press. That’s in some ways still my favorite book. You know, in your twenties, you’re going through all these wonderful changes in your life, and you see this book come out. It’s a beautiful book. They put it together so well. That was 1982.

Thirty-seven years ago, and still in print. That’s a very technical book too. But that launched me into a positive relation with publishing. And then when you came along with Race Matters, BOOM, tore the roof. Tore the roof off!

DC: Do you have publishing plans?

CW: I’m working on a book on Abraham Joshua Heschel.

DC: How did you settle on that?

CW: I’ve been teaching a class on Heschel for a long time. But now with the Israeli-Palestinian issue becoming more central, and with so many young Jewish brothers and sisters undergoing a magnificent moral and political awakening around the Israeli occupation, I want to intervene by bringing the legacy of Heschel into that conversation. Susanna Heschel, his brilliant and courageous daughter, is speaking in her own voice in a powerful way, but that great Heschel legacy needs to be brought to bear in understanding how we can talk about Jewish humanity, Palestinian humanity, Arab humanity, in a prophetic way, deeply rooted in a Jewish tradition from Amos to Esther all the way to Heschel himself that embraces the oppressed and dominated and colonized and occupied peoples. So it takes all of us outside of our worst selves and tries to put us on higher moral ground. Then we need an analysis of empire, an analysis of structures of domination, and then the ways people resist. What would Heschel, in light of his commitment to the prophetic tradition, have to say about the Boycott, Divest, and Sanctions movement that I support? When Martin King was isolated all by himself, Heschel was one of the last ones there, and it was Heschel who brought pressure on Martin to come out against the war. Stokely Carmichael and a number of activists from SNCC and the community did too, but especially Heschel. Of course Heschel himself led the concern against the war in Vietnam. And King and Heschel were like brothers, very close. That story needs to be told.

DC: It must be so hard to write in the current climate.

CW: It’s very hard. Especially with the changing realities, the changing voices. When the Marc Lamont Hill controversy surfaced, I wrote for The Guardian trying to both defend him but also have my own critical engagement with him around a certain kind of language. How do you really speak truthfully about two thousand years of the hating of Jews that’s constitutive of that history? It’s not some side thing, you see. So the issue of security becomes very visceral and material, and yet, if you have a conservative Israeli elite that hates Palestinians, then on moral and spiritual grounds you’ve got to have the same level of resistance against Palestinian-hating as you have against Jew-hating. And Heschel provides a way of keeping track of that so that you don’t fall into just ugly name-calling. Or, put it this way, it’s the shift from a melodramatic narrative—all the good on one side, all the bad on the other—to a real, tragic, comic one that’s tied to revolutionary fervor. That’s a very, very delicate connection. Although both Heschel and King considered themselves progressive Zionists, and I am neither a Zionist nor a nationalist of any sort. Their prophetic voices force us to come to terms with whether there is any moral and spiritual substance left in the Zionist movement, even given the non-negotiable point of Jewish security in any future state.

DC: That’s a hard thing to even imagine these days, when everything is about taking sides.

CW: It’s all one-sided. Even given the complexities, we must take a stand, but never in a self-righteous manner.