Something has changed, as most everyone in the climate movement agrees, and we have plenty of signposts that track the shift, from David Wallace-Well’s 2017 New York Magazine piece, The Uninhabitable Earth, to last year’s Deep Adaptation: A Map for Navigating Climate Tragedy, a paper downloaded by the hundreds of thousands. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change made the shift official with its own dramatic contribution, the landmark Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C.

All of a sudden, the air has become crisper, the view clearer, the danger before us more obvious. Classic climate denialism has lost its legitimacy and stands revealed as just a right-wing scam. And everyone knows it. How could we not? The natural world has given us rainstorms and firestorms as reminders. Innovative new activism has given us the Green New Deal, a watershed by any reckoning, and the Extinction Rebellion has given us its unforgettable new protest exhortation: “Tell the truth!”

If we had to choose one voice, one single slogan, to represent the pivot we’re now passing through, as Wen Stephenson suggests in the Nation, we might well pick the Czech playwright and ex-president Vaclav Havel and his notion of “living in truth.” More of us are choosing to live that life. We’ve become sick of the lies. Even the comforting lies.

So where does this all leave us? Three key points.

First, despair is looming, and for good reason. Take a look at Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene, the so-called “Hothouse Earth” paper, or at least know its bottom line: Our environmental “tipping points” have actually become “tipping cascades,” and these cascades, once they really get moving, will amplify each other in ways all but impossible to stop. By the time our global temperatures arrive at 2°C, if indeed they do, we will face a real risk of runaway feedback.

Second, we have the technology, and the money, to save ourselves. Take a look at the ongoing work of Project Drawdown or skim Carbon Tracker’s 2020 Vision report. Encouragement everywhere, along the lines of “superconducting windmill generators and utility-scale flow batteries.” As for the money, suffice it to say that “we” will have plenty of it, plenty of financial and institutional capacity, once we pry this capacity out of the hands, or rather the tax havens, of the elites.

Third, we have to prepare for the possibility of a proper awakening. We can certainly hope that the more people understand the depth of the danger—the Earth will be fine, but many species will not make it, and our civilization may not either—the greater will grow people’s frustration, their anger, and their willingness to contemplate transformations appropriately scaled to the danger. But “living in truth,” by itself, cannot be a transition strategy, just a beginning. If we plan on “living in truth,” we had best go all the way.

We stand now in an awkward spot: We know how much trouble we’re in, but we don’t know what we’re going to do about it. More precisely, we don’t have a strategy, or even a positive, attractive transition story that we actually believe in, in the sense of believing we have a transition plan that could actually meet the challenge. We won’t have this believable plan until we recognize the ultimate “truth”: that our climate crisis remains inherently and irreducibly global. Our response must be the same.

Two things will save our civilization. The green technology revolution, now arriving in force, offers up the first. But we also need sustained and visionary planetary-scale cooperation, and such cooperation will only be possible if our climate mobilization simultaneously mitigates today’s levels of extreme economic inequality. Economic justice at the international level has to be part of our core story.

Inequality amounts to more, we need to realize, than just a problem of poverty. We have fundamentally a problem of wealth. The Climate Equity Reference Project (disclosure: I co-direct CERP) is working to clarify this problem, and I’m going to take the liberty here to pull a few charts we’ve prepared to support the Civil Society Equity Review Coalition, an effort now evaluating the fairness—and unfairness—of the national pledges of action emerging under the Paris Agreement signed in 2015.

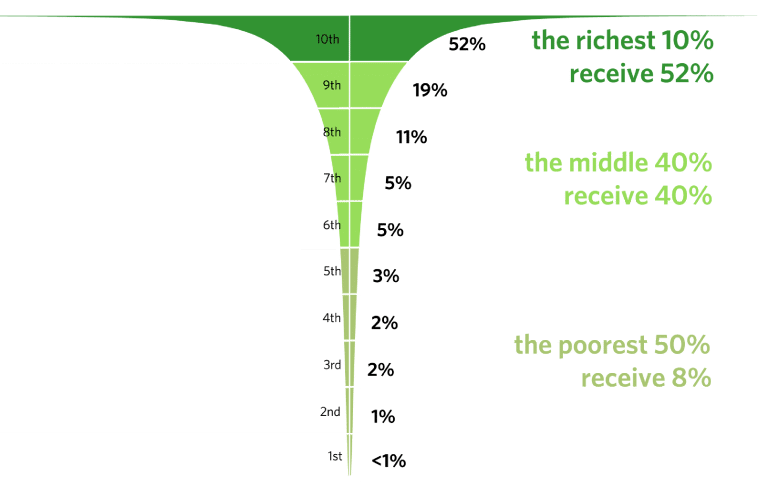

Consider this “champagne glass,” a figure that represents the income distribution of humanity as a whole. This stacked figure’s ten deciles each represent the income of one tenth of our global population, and you’ll quickly notice that this champagne glass doesn’t look like any glass you’d actually want to put to your lips. That’s because our global income distribution stats define a very sharp edge indeed, with the richest 10 percent of humanity—the dark green decile—receiving 52 percent of all global income and the richest 1 percent and 0.1 percent receiving an outsized share of that total.

In contrast, the poorest half of the world’s people—the five lowest population deciles that define the stem of the glass—receive less than one-tenth of total global income, an amazingly radical stratification that cannot be justified by any even remotely defensible theory of justice.

But step back a second. Why is this discussion about climate crisis talking about income distribution?

The first reason: Greenhouse gas emissions, whether calculated for individuals, nations, or income groups, highly correlate with income.

The second: Today’s extreme levels of income stratification—and, even more fundamentally, wealth stratification—have become a global existential danger. Extreme economic inequality turns out to be a social poison that makes it almost impossible for us to mobilize to save ourselves and our civilization.

Note that, as per the champagne glass above, our wealthiest live starkly different lives from our poorest, many of whom (still) survive on less than $2 per day and in so doing generate an almost negligible amount of greenhouse gas emissions.

Between these two extremely rich and poor groups sits what many call the “global middle class,” a term hardly appropriate when applied to the middle of the global income distribution, given the rich-world connotations of comfort and security that come with middle-class status. In fact, most of the people in the so-called “global middle class” rate as extremely poor.

Consider an individual with an income of $20 per day. That income may be ten times higher than an abject poverty threshold of $2 per day, but even at this $20 level almost all household income immediately goes to the daily struggle of meeting basic needs. Fully two-thirds of humanity live on less than $20-per-day, including nearly half of the “middle” 40 percent in our champagne glass.

Disparities in emissions closely parallel disparities in income. Wealthy people overwhelmingly reside within the world’s wealthy countries, and their “luxury emissions”—to use the jargon of the global climate justice movement—support lifestyles that simply cannot, without some extremely hypothetical technological miracle, be shared by all. Clearly, in any fair approach to international cooperation, these wealthy populations, with their luxury emissions, would be treated differently from poorer populations.

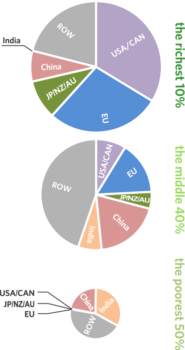

We can approach the issues here by taking a different view of the three global income classes defined in the champagne glass above, this time focusing on the nations from where the members of these classes hail. This second figure offers that different view, with three pie charts that represent, by their sizes, the share of global income that goes to the top 10 percent, the middle 40 percent, and the bottom 50 percent of the global population distribution.

We can approach the issues here by taking a different view of the three global income classes defined in the champagne glass above, this time focusing on the nations from where the members of these classes hail. This second figure offers that different view, with three pie charts that represent, by their sizes, the share of global income that goes to the top 10 percent, the middle 40 percent, and the bottom 50 percent of the global population distribution.

As you can see from the top pie chart, the majority of the people in the top 10 percent live as citizens of the “old rich” countries, more than half in the United States, Canada, and the European Union, with many of the others from Japan, New Zealand, and Australia. Notably, a good fraction does go to people from China, though even at this very rough level of detail—the global top 10 percent hardly consists of only the truly wealthy—we see far fewer Chinese than Americans and far, far fewer in per-capita terms. Global emissions, the New York Timesrecently told us, could be cut by a third if humanity’s richest 10 percent cut its use of energy to the same level as affluent, comfortable Europe.” Our globe’s richest 10 percent—the richest 500 million adults—bear responsibility for about 50 percent of all global emissions.

The second pie chart, sized to represent the middle 40 percent of the global income distribution, defines a considerable range of incomes. This middle class contains far more Chinese than does the top decile. It also contains significant numbers of people from the United States and Europe. The crucial point here: At home, many “middle 40 percent” people would be considered poor. But in the global scheme of things they rate as not so very poor, a critical point that helps us think about the justice of rich-world consumption patterns.

The third pie chart’s most notable feature? Its small size. This chart represents half of the world’s people, the poorer half, and the people in it rate as very poor indeed. They receive less than a tenth of global total income. Note, too, that some very poor people do live in the United States, Europe, and other regions of the developed world. But the developed world does not have enough of them to rate a visible slice of the bottom pie chart.

In all this, the single most important takeaway has to be that our “twice divided world”—riven on one axis between the rich and the poor and on another by the North and the South—gives almost everyone good reason to feel confused, angry, and afraid. This is no small thing. To face the rigors of emergency climate mobilization, we need to stand together. Our inequality makes this standing together more difficult. In particular, the dynamics of globalization as they have unfolded under neoliberal capitalism have pitted the rich-world’s poor against the poor-world’s poor struggling to enter the “global middle class.” The poisonous consequences of this tension—think “populism”—have become obvious everywhere.

Then we have the problem of the truly rich, who elude the analysis above. These rich do not all reside in wealthy countries. To be sure, the “old rich” countries do host the vast majority of the rich—12 percent of Americans rest in the global 1 percent, a group with an entry threshold of about a million dollars. But top 1 percenters appear everywhere. Even poor countries like India have a small wealthy stratum, full of deep pockets who share an inherent conflict of interest. Do they stand with their poor countrymen or with the global rich? This has become a source of real confusion.

How to sort all this out? One good way: Look at where the money—and the capacity to address the climate crisis—actually sits. Taking this look gives us a nuanced picture that both resembles and refutes the classic model of the post-colonial world and its globe divided between “developed” and “developing” countries. It’s not quite like that anymore.

Zoom in from the global 1 percent to the world’s “ultra-high net worth individuals,” the elite the annual Credit Suisse Global Wealth Report defines as having at least $50 million, and you’ll see that 47 percent of these ultra-rich reside in the United States, 22 percent in Europe, and 11 percent in China. In this distribution, the shape of history remains still clearly visible—the past, as Faulkner noted, is not even past—but so does the emerging world, which if recent trends continue stands primed to see an income-distribution convergence between China and the United States.

All this weighs heavily on the climate transition, for inequalities in wealth translate directly into inequalities in power. Wealthy elites set frames and agendas and also overbear fragile democracies with their preferences. They engineer trade relations that undermine community resilience around the world, spread disinformation, and sabotage efforts to mobilize at a necessary scale. This power explains a big part of why we’ve arrived at our current reckoning. And, remember, we could easily have worse to come.

Societies under environmental pressure tend to stumble toward collapse when their elites, those who set collective priorities and allocate resources, distance themselves from the realities and afflictions of their population as a whole and come to act so much by the logic of narrow self-interest that they become blind to the larger predicament. We can say the same for a world where rich countries let poor countries fall to famine and rising seas, blind to the near certainty that, down this road, they will ultimately share the same fate.

If we’re going to stabilize the climate system, we’re going to have to do so within the political-economic maelstrom of our twice-divided world, and we had best give some time to understanding its dynamics. These dynamics, to be sure, go beyond income—race in particular rates a critically important force in human affairs, and so do other dimensions of structural oppression—but it’s fair to say that the forces now buffeting society rest rooted in extreme income inequality.

Unfortunately, we’re not exactly on the road to centering inequality in our thinking. But then again, we’re not on the road to centering any really global view of the climate challenge, and this absolutely must change. Today’s Green New Deal vision, fantastically useful though it may be for foregrounding domestic inequality, does not seem likely to do the same for international inequality.

The U.S. Green New Deal has, thankfully, made a tentative move towards global solidarity, recognizing this past February the need to “help other countries achieve a Green New Deal,” though offering nothing substantive to back this up. Minimally, every national campaign needs an international justice plank, because we’re not going to get anywhere near the Paris temperature targets without international sharing and cooperation. And we’re not going to get near those targets either without taking the global justice challenge into proper account, for the simple reason that any meaningfully deep and rapid global climate mobilization is going to be expensive. We’re going to have to figure out how to pay for it.

I’d like to suggest here that we declare a moratorium on vague critiques of the Paris Agreement. The Paris accords were built to be strengthened—and they will be, if and when the world’s nations decide to strengthen the original agreement, a task by the way that is going to be a lot easier with the first version on the books than it would ever have been without this first version.

So think about Paris, the Green New Deal, and the green technology revolution as building blocks. The question becomes how to put them together. We will clearly need to redirect trillion-dollar investment flows from the “brown” projects that attract them to green projects, and that in turn will mean thinking globally, pumping massive amounts of public money into a Green Climate Fund and other cooperation mechanisms that can animate the Paris system.

In practice, this will mean achieving the first-round pledges of national action, all around the world, even as we push our respective nations—poor nations as well as wealthy nations — to put stronger pledges on the books. Remember the IPCC deadline: We need to be aiming for a global emissions level about 45 percent below the 2010 level by 2030. We’re not going to hit that target with bottom-up action alone.

To meet that target with a properly scaled response, we’ll have to get down to hard and practical questions about making the climate transition fair, globally as well as within wealthy nations like the United States. And that will mean a kind of transformational justice, yet to be fully invented, that takes proper account of both the national rich and the global rich on one side and the national poor and the global poor on the other. Both of these divides could not be more real. Both, taken together, define our real conditions of life.

Our bottom lines? Most people on our planet remain very poor, and the global rich have a lot of money. They also have the power to decide whether we sink or swim. Think about it.

Tom Athanasiou currently co-directs the Climate Equity Reference Project, a long-term initiative designed to provide scholarship, tools, and analysis that help advance global climate equity. He’s currently writing a new book. The working title: Everybody Knows: A Primer on Climate Emergency, Internationalism, and the New Age of Inequality. He can be reached at [email protected].