She says: when are we gonna meet?

I say: after a year and a war

She says: when does the war end?

I say: the time we meet—Mahmoud Darwish

They made it plain to everyone, however, and above all to the king himself, that although he had plenty of troops, he did not have many men.

—Herodotus

I would happily claim to be the first in the folds of Arabic science fiction to write Palestinian resistance literature (adab al-muqawama, أدب المقواه), but, alas, the Egyptians beat me to it. Muhammad Naguib Matter, for example, who was an engineer by vocation and a science-fiction writer by passion, penned “A Weapon Fashioned of Waste” long before I even began to write.1 (The story begins with Palestinian resistance fighters learning to trick the pheromone-sniffing Israeli missiles by using urine trails, after which the Palestinians devise their own phosphorous bombs, also extracted from urine.)2 Ahmed Khaled Tawfik’s Jonathan’s Promise (2015) and The Last Dreamer (2009) also stand in the resistance genre. (The first text is about an upside-down world where Arabs live in the diaspora and the United States decides to give them a homeland of their own. The second is a fantasy series in which Che Guevara is resurrected from the grave, cloned by Chinese geneticists, and sent to Iraq to give the United States some hell. He later makes it to occupied Palestine to do the same but is apprehended and killed by the Israelis.)

One of the earliest works of Arabic science fiction, the 1962 Algerian novel Qui Se Souvient De La Mer (Who Remembers the Sea) by Mohammad Dib, was also part of the resistance-literature genre and was written in the heyday of the struggle for national independence.3 (Instead of speaking explicitly about the French occupation, Dib has alien robots ransack his homeland up against a few bands of brave men armed with handguns. Nonetheless, the human protagonists win in the end.) Sadly, since Qui Se Souvient De La Mer, nothing was written in the resistance or military science-fiction genres, in Algeria or elsewhere, until 2001 when Hosam El-Zembely published the dystopian novella America 2030. (In it, the United States degenerates politically and ignites a nuclear war as a team of operatives tries desperately to destroy a secret weapon, tipping the balance of terror.4 And this was written before September 11—only for Egyptian and most Arabic science fiction to quietly forget the very real attacks against Arabs and Muslims since then.)

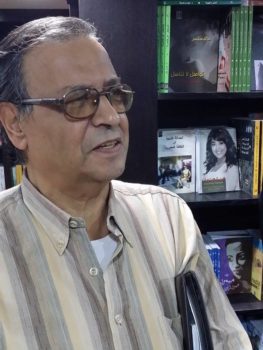

It is almost a truism now that the history of Arabic science-fiction writing is characterized by fits and starts.5 Tragically and inexplicably, the same seems to hold true of Arabic resistance literature. I get this from the horse’s mouth, so to speak, having spoken with the resident expert on resistance literature, Egyptian author Al-Sayyid Nejm.6 Almost from his first uttered word, he explained that the category itself is new to Arabic literature, insisting that Palestinian author Ghassan Kanafani was the one who coined the term. Previously, it only existed in residual form, under the labels adab al-hamasa (أدب الحماسة) and al-harakat (الحركات)—the literature of agitation and of movements.7 The same goes for war literature, he added, on which he is also an expert. What is more, neither resistance nor war literature are parts of higher education, at least in Egypt.

There are no specialized courses in either resistance or war literature in Egypt. Books and stories and poetry on the topic are taught, but in generic courses about classical and contemporary Arabic literature, the contemporary Arabic novel, Arabic literature in translation, and so on. Even the 1973 October War, one of our few victories, has not received the literary and critical attention it deserves. This has prompted critics to describe the genre of war stories as almost a foreign entity that has entered our midst undetected.8 How could this be, when almost the whole Arab world struggled for its independence against foreign colonizers? When a frontline nation like Egypt fought so many wars and not just against Israel? After all, the 1956 Suez War was over the nationalization of the canal, primarily in the face of the British and French empires. If you go to an Egyptian bookstore, you will find the same telltale pattern of malign neglect. It will be hard to find anything written by Egyptians on the topic, whether fiction or nonfiction. I say this having just attended the fiftieth Cairo International Book Fair. I did not find anything of Nejm’s there either, except at one solitary (non-Egyptian) bookshop that had an overly expensive book about him.

In the meantime, the world has passed us by. The Western literary tradition admits to the category of resistance literature and the Italians, Dutch, and French have rich, varied, and highly celebrated traditions of their own, including ones that transcend the Second World War.9 More recently, the concept has expanded to include postcolonial literature, women’s literature, minority rights, and the plight of the working class.10 There was even a conference on all this at the American University in Cairo in February 2018. It was titled Resist! In Memory of Barbara Harlow, 1948–2017, and was organized in celebration of Harlow’s classic Resistance Literature (1987). She was especially keen on the plight of the Palestinians, translating Kanafani into English and championing the rights of Palestinian activists incarcerated in Israeli prisons.11 If Westerners can cheer on and study our causes, that we should be able to do the same.12

Not having a genre label is debilitating. A cursory look at the composition of distinguished Egyptian authors in the field helps illustrate this. While many have written about war, peace, foreign occupations, and acts of resistance, very few have specialized in resistance literature. Egypt’s very first published novel, Zaynab (1913) by Muhammad Husayn Haykal, is an oft-cited example of resistance literature, but that was not the chief genre in which Haykal wrote. Naguib Mahfouz is another example of someone who wrote extensively about resistance in Egypt through the characters of his many novels, from supporters of the Wafd Party and socialist intellectuals to disgruntled citizens and hoodlums.13 The catch is that he did this indirectly—his concerns lay elsewhere.

Mahfouz has been categorized as a writer of generational novels, a social historian who tried to tackle politics through detailed accounts of people and personas in their everyday lives.14 Even when he dealt with the October War, such as in The Day the Leader was Killed (1985) and Before the Throne (1983), he focused more on the social aftermath, when the legacy of Anwar Sadat’s post-1973 economic reforms were put on trial, and not so much on the military and diplomatic victories.15 Mahfouz’s only novel that formally dealt with resistance was his historical work Kifah Tiba (Thebes at War or The Struggle of Thebes, 1944). Therefore, without a formal genre or university courses, academic journals, magazines, and publishing houses specializing in the field, there was nothing to institutionally sustain this kind of literature. And the same goes for war stories.

A contrast is called for here—namely with the Iranian experience. Iran enjoys distinguished and internationally recognized literature and visual art on war and resistance.16 Ahmad Dihqan’s Journey to Heading 270 Degrees, Seyyedeh Zahra Hoseyni’s One Woman’s War, and Habib Ahmadzadeh’s Chess with the Doomsday Machine are three especially critically acclaimed examples.

These genres grew out of the Iran-Iraq war, but were carefully promoted during the early days of the Islamic Republic under the tutelage of Mustafa Chamran, the republic’s first minister of defense who also helped train guerrillas in Lebanon.17 Since then, the Hozeh Honari (Art Club) was set up with its own Office of Literature and the Art of Resistance at the Center for Literary Creations.18 Egypt has not nearly been so lucky since 1973. Another factor was the ideological gulf that formed in the wake of Camp David, as Shawqi Abd Al-Hamid Yihya argues in The Novel in October 1973 (2017). Many authors were proud of the October victory but also glad with the ensuing peace, while others understood the peace as a betrayal and forgot the significance of the victory.

Speaking to Nejm again, he explained that even authors who did specialize in war stories did so based on their own varied personal experiences. Some were civilian media correspondents during the War of Attrition (1967–70) or the October War (1973), some were conscripted soldiers who fought in those wars, and some were resistance fighters who fought in Port Said in 1956 or Ismailia in 1973. They did not go out and study Tolstoy to pen their works, preferring to rely on their own personal narratives as sources of inspiration. Consequently, their works were not the result of a systematic research project that could have turned the tables and established a new subgenre. This is tragic given the impressive set of Egyptian names besides Nejm: Fouad Higazi, Youssef Al-Qaied, Muhammad Al-Rawi, Ahmed Hemeda, Mustafa Nasr, Said Abu Khaiyr, Qasim Massoud Elewah, Gamal Al-Ghitani, Ihsan Abd Al-Qudus, Ammar Ali Hassan, Hassan Al-Bindary, Muhammad Muhammad Al-Nahas, Gamal Hassaan, and Abd Al-Fatah Rizk, not to mention seminal nonfiction accounts. One suspects that there is a generational factor involved too. I was pleased to find an Iraqi friend, from my father’s generation, talking about the Palestinian cause and its centrality to Arab liberation despite the state of his own country. You would think that the devastation of Iraq and the U.S. occupation would cajole him to think otherwise, but no, Palestine was still center stage. His justification was that his generation grew up at a height of Palestinian struggle, making it a fundamental part of their identity. Not coincidentally, he lamented how young people in the Arab world were not nearly as aware of and engaged with the Palestinian cause. I found the same set of attitudes speaking to Nejm—he fought in the October War and his commitment to Palestine has been unswerving ever since. And thank heavens for that, because had it not been for his persistence, war literature would never have received any critical attention in Egypt. He made sure to get Al-Ahram newspaper on board and has, to date, written seven critical texts on the genre, in addition to his own numerous stories and novels.

There is more at stake than just recounting tales of heroism behind enemy lines. Almost in anticipation of the broadening and deepening of the concept in the Western tradition, Nejm argued early on that resistance literature, or adab al-muqawama, is not just about the fight for freedom but the struggle for an identity, which means tying tales of war and resistance with the historical novel and the quest for cultural independence in the face of colonialism. More than that, it means utopia and an extended dialogue over the nature of the virtuous city and visions of the future.

Mixed Legacies: Continuity andChange in Early Arabic Literature

Reading up on resistance literature in Arab history, one discovers many of the same problems. Accounts of Arabic resistance poetry and storytelling are contradictory at best. Abbas Khidr’s Resistance Literature (1968), a minor classic in its own right, argues that Arabic resistance literature only began with the Crusades, in the form of poetry and folk stories. Shawki Dayf’s Heroism in Arabic Poetry (1970), another classic, explores the continuous stream of war poetry from pre-Islamic times to the early Islamic conquests, with a much larger tradition developing during the Crusades and the Mongol invasions.

Unsurprisingly, the characteristics of Arabic resistance literature are also disputed. Some accounts state that resistance literature was traditionally very shallow at the level of narrative and plotting, with an emphasis on oratory and two-dimensional characters extending from pre-Islamic poetry—called Jahili poetry—into the modern period. This is chalked up to the fact that theater never developed in the Arab world, since the classical Greek heritage had the advantage of heroes who were often portrayed as flawed. Their hamartia always led to their later undoing, after victories and despite their divinity.19 While there is no shortage of tragedy in Arabic stories, the poetry that was produced by Arabs tended toward propaganda with squeaky clean heroes and an emphasis on aesthetics at the level of form over content; rhythm and the music of the words, as opposed to a storyline with a beginning, middle, and end. Apart from Youm Al-Bassous, cataloguing a forty-year-long war, there are no epic poems in the pre-Islamic literary tradition that are in the same vein as the Iliad and the Odyssey.20

At the same time, other accounts note how sophisticated Jahili poetry was when it came to breaking away from monologue and relying on an extensive narrative frame.21 Heroes engaged in dialogue and often challenged prevalent norms, even challenging their tribes on matters of war or trying to dissuade rivals.

There is a lot of truth in all of these diverse positions, but the problem is actually simpler, to take a page from Nejm again. He defines resistance literature as the literature of “any group or people that are aware of their identity and fighting for their freedom against an aggressive other, and for their collective deliverance.”22 The central problem Arabs had before Islam is that they were not aware of themselves as a people. (Recollect Ho Chi Minh’s immortal phrase: “Our secret weapon is nationalism. To have nationhood, which is a sign of maturity, is greater than any weapons in the world”). You can see this in May Khalif’s own book on the hero in Jahili poetry (1998). Even when the poet engages in a dialogue on the nature of war with his sweetheart, opponent, tribe, or even horse, he only represents his own views.23 It is not perceived as part of an Arab view on society.

As for the tortuous pedigree of Arabic resistance literature, it seems that war poetry was in fact very well developed in the pre-Islamic period, but that it fell into neglect and stasis in the early Islamic period as the Arabs settled down and became so-called civilized, and as poetry moved into other avenues—theology, beauty, philosophy. It took on a new lease of life and expanded during the Crusades-Mongol period, only to die down again later, with Turks usurping the position of Arabs in warfare and politics. That is, until the colonial period and the rise of Arab nationalism and the decline of the Ottoman Empire.24 But even then, it was patchy. It was significantly more developed in certain parts of the Arab world than others, especially in Palestine and Algeria, while later falling into disfavor in other quarters. For example, I certainly got this distinct impression speaking to Palestinian author Samir Al-Jundi. He noted how Algeria was practically the only place where you were celebrated as a resistance author in the Arab world!

That is not all, however. There are other problems operating beneath the radar. Even during the peak period of resistance literature in the Crusader and Mongol period, when the great epics or siras of Sayf ibn Dhi-Yazan and Antara inb Shaddad were conceived, they still tended toward this older format and punchline. This is a criticism that is voiced today in Arab literary circles when it comes to war and resistance literature.25 The novels are not internal enough—that is, they do not sufficiently delve into the inner world of characters, and dialogue tends to be flat. We can add that there is an overemphasis on gritty realism, another characteristic inherited from the nether days of pre-Islamic poetry and early Arabic storytelling. Stories written by soldiers in the field, such as Samir Al-Feyl’s How Does the Soldier Fight without a Helmet (2001), place the emphasis not so much on battles, military maneuvers, and attempts to find out about enemy motives, but rather on the suffering of the individual soldiers and their own personal stories regarding poverty and other social problems (dead fathers, inheritance conflicts, substandard military equipment, and so on).

This is not just the case with Egyptian literature, but with Arabic literature more broadly. I was reading a short story by a Syrian author once and the protagonist kept worrying about his extended family, his home, and his village the whole time he was in a foxhole up against Israelis—and the story was written in the 1960s in the heady atmosphere of Nasserism and Baathism.26 An even more poignant example is Jordanian author Aqlah Haddad’s short-story collection Praise be to the Nation (1990), which ties a heroic account of a Palestinian guerrilla fighter (in “Lover of the Homeland”) together with several stories filled with anxieties about war (like “Returning to the Battlefield”).27 In fact, Haddad’sbook is almost antiwar literature (so much for Arabs’ stereotypical warlike spirit). Condemning war as immoral is one thing, but inefficiency in fighting is another, as is romance and the avoidance of excitement, intrigue, and ingenuity.28 (People forget that the Sayf ibn Dhi-Yazan and Antara ibn Shaddad siras are both epic love stories and tales of swashbuckling). Russians are as partial to misery and suffering as we are, but they know how to talk about outsmarting the enemy and enjoying themselves in between breaks. The English have written a continuous stream of novels about the exploits of the Special Air Service, from the Second World War to the Gulf War, and works of pulp so detailed that you can learn more about war from them than a military manual. Resistance and war literature is not just about battles, but about entire conflict scenarios—something not as often depicted in the Arabic literary tradition.

The Modern Interlude: Class Conflicts and a Conflicted Literature

Fortunately, the story is not all doom and gloom. Palestinian resistance literature helped break the bounds of many of the literary taboos holding Arabic literature back. As Ibrahim Fathi explains in his introduction to Radi Shehata’s critically acclaimed The Locusts Love Watermelons (1990), while resistance literature in Arab history came in the form of siras, malahimas, and taghribas (epics of exile or migration), societal antagonisms held back literary progress. Conflict between the ruler and the ruled, and often between rulers and the story’s fighting hero, is much more clearly and explicitly stated in Greek epics.29 In traditional Arabic literature, such conflicts are often swept under the rug. For example, in Arabic folk literature, the hero is usually a prince, bandit, foreigner, forcing the poor to only play secondary roles, if any. But, given the popular audience, storytellers compensated by giving the hero both what were perceived as upper-class and lower-class characteristics, or by giving him a common-folk sidekick.

Another debilitating feature of older resistance literature is its timeframe. The stories are always of past glory and adventures, with no regard for actual historical events. In the case of the Ali Al-Zaibak sira, for instance, you have Caliph Haroun Al-Rashid living and ruling at the same time as the Tulunids in Egypt.30 This makes it not only hard to draw historical lessons, but it freezes us in time. Resistance literature is meant to be open-ended, with a better future in sight. Palestinian literature helped break that older mold, as fond as Palestinians are of folk heroes and the siras and epics of the past. In Palestinian resistance literature, the fight continues until victory is accomplished and a better future created. In particular, it was the social contradictions and injustices of the past that led to defeat.

Everyone participates in the fight, specifically the poor and the downtrodden, who are given a significantly bigger role than they were in traditional literature and its didactic style (البلاغة الخطابية) of oratory writing.31 Ibrahim Fathi, bemoaning the lack of individual and psychological focus in older resistance literature, adds that the Palestinian contribution has helped in this regard but has still not quite moved enough toward the modern novel format. This invariably happens when you write resistance literature in the middle of an actual conflict, becoming part of military morale literature. Still, a lesson from Palestinian resistance literature is that it was able to break away from militarism. A whole new genre within a genre developed with the Palestinian intifada, pioneered by the likes of Radi Shehata and Muhammad Watad in his novel The Ululations of the Intifada (زغاريد الإنتفاضة, 1989). Nevertheless, it is a shame that there is no science fiction as future-oriented as Palestinian resistance literature is.

None of this, of course, should discount from the Algerian contribution to resistance literature. One of the most interesting and imaginative examples of contemporary Arabic resistance literature comes in the form of two magical-realist fantasy novels by Djamel Jiji: his brilliant Les Envahisseurs des Rêves (2009) and the sequel Le Retour de Jésus-Christ (2015). The former is set in a village struggling to survive against an invading force—modelled on the United States in Iraq—with the children especially suffering and fighting back through their imaginations.32 The Algerian contribution, moreover, is much broader in its understanding of resistance, not focusing just on underground warfare but also cultural resistance and withstanding the temptations of the Western imperialist, such as through sex, alcohol, and skin-deep integration. The same, amazingly enough, applies to Palestinian resistance literature within Israel for 1948 Palestinians.33 Algerian resistance literature also tackled head on many homegrown societal ills, such as poverty, ignorance, and exploitation, particularly against people in the countryside.

Algerians have also understood something us Eastern Arabs have not—namely, the need to resist Western colonization through immersing ourselves in Western cultural itself, to cite Muhammad Masayif’s classic The Arabic Algerian Short Story in the Era of Independence (1982). Despite all the talk about socialist realism and the need for a revolution in education and for positive role models, Masayif insists at the same time that Algeria cannot isolate itself from the rest of the world, and that both the revolutionaries and the intellectual classes knew this. The trick was to assert your identity first, through self-exploration, history, and language. Once you are sure of yourself, you no longer reject all things foreign due to a (justifiable) knee-jerk hatred of the modern world, traumatized over what happened under the French occupation. Of course, at the same time, you also do not blindly follow every fad or fancy coming out of the North American and European continent. The selection process has to be reasoned and methodological, taking into account local needs, problems, and priorities.

Algerians also seem to have benefited from their African and francophone identities.34 Resistance literature is far more well-developed on the African continent than in the Eastern part of the Arab world.35 Of course, there is still the tragic absence of science fiction, which is inexplicable given Mohammad Dib’s early contribution. Nevertheless, the magic realists have been able to make up for this area of neglect in Algeria and—again—in Palestine.

Resistance literature is intimately connected to both history and utopia, whether we should define ourselves in reference to a static past or reinvent who are, wanting to move on into the future.36 Thankfully, Palestinian authors are very adept at surrealism, stretching from Emile Habibi to Samir Al-Jundi and the critically acclaimed Ibrahim Nasrallah. Al-Jundi, for example, has written plenty of realist literature, but his novel Phantasia (2016) is firmly surrealist and set all over the Arab world as a Palestinian from the West Bank struggles to define his identity by travelling from country to country to learn from others and see how they are faring. The same goes for Nasrallah, who started out with compendious historical novels only to surprise us all with The Second War of the Dog, set in a future replete with world-bending technologies.

It may be the case that these authors are still unpacking the present through this future lens, but it is a step in the right direction and evidence that the past is no longer enough to quench their thirst—both as authors and activists. Moreover, since Nasrallah’s novel won the Booker Prize for 2018, it has made the uphill task of writing Palestinian science fiction a whole lot easier and brought the prospect of international recognition a little closer.37

The Torchbearer’s Prerogative: Fantasy and Science Fiction from Now On

Science fiction is no stranger to war and resistance, whether in the context of alien invasions or thoroughly human enemies. There is a long and proud tradition of this, stretching from Starship Troopers and H. G. Wells’s War of the Worlds to television series like V and anime like Grendizer and Battleship Yamato. Themes of identity, belonging, and future selves are all also evident in science fiction’s exploration of war and resistance, such as in Robert Heinlein’s Between Planets (1951), with a young human protagonist marooned on Venus during the rebellion of the planet’s human colony against the Earth federation, with aliens aiding the human resistance. It is pretty clear that the Venus rebellion is supposed to be a reenactment of the American war of independence, as in The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress (1966).

Resistance literature as a label is now openly acknowledged in the folds of science fiction and entire subgenres like military science fiction have taken shape as well.38 Yet, other genres that emerged over the years, like cyberpunk and steampunk, also delve into resistance movements and military history, diversifying the tools at the disposal of underground movements and official armies alike. Not to mention feminist science fiction, with Ursula K. Le Guin, Suzette Haden Elgin, Octavia Butler, Nalo Hopkinson, Dorris Lessing, and Margaret Atwood.

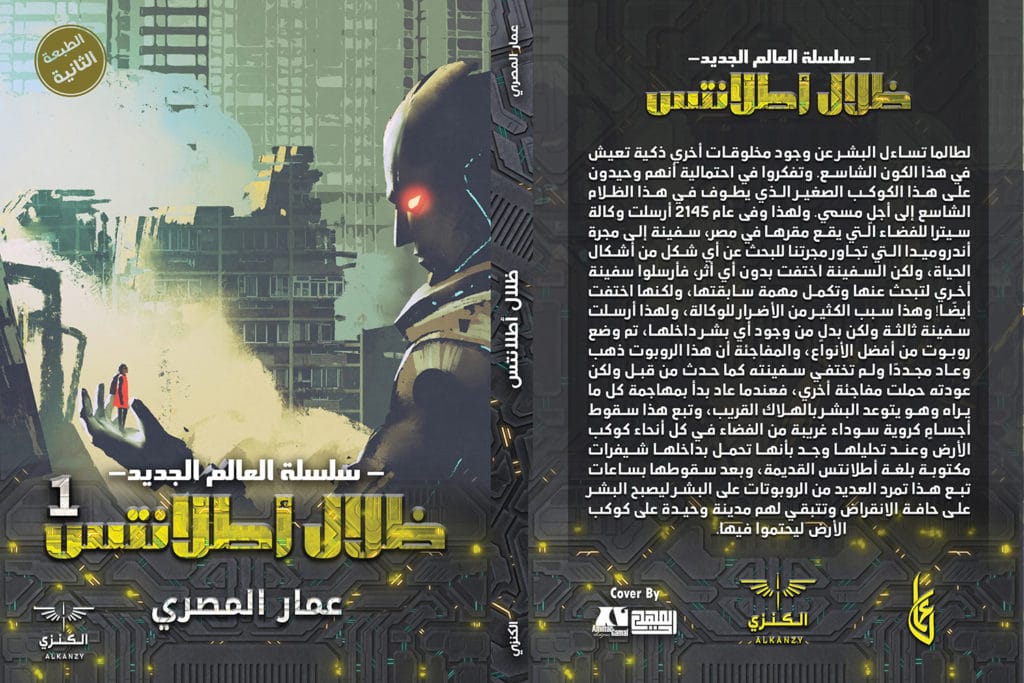

Things look promising in the Arab world too. Ammar Al-Masry, for instance, has already completed two novels in his planned Atlantis trilogy—a utopian alien-invasion epic in which humans battle robots controlled by alien intelligence.39 Each novel is in the 400-page range. Ahmed Al-Mahdi’s Malaaz (2017) is another postapocalyptic novel that has been described both by critics and the author as an example of resistance literature. Not to forget the legacy of Mohammad Dib and Nejm, along with Muhammad Naguib Matter and Ahmed Khalid Tawfik cited above. Moreover, Ammar Al-Masry, Ahmed Al-Mahdi, and Muhammad Naguib Matter are all members of the Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières.

Of equal, if less evident, significance are some smaller Egyptian novels in the pocketbook genre. Two examples in particular stand out: Treacherous Sands (2014) by Muhammad Al-Bidewi and The Accursed Experiment (2008) by Muhammad Samy.

Treacherous Sands is the second book in a four-part series with a time-traveling secret operative named Shihab, who goes back (and forward) in time to “fix” politicians’ mistakes in hope of a better future. In book two, Shihab prevents the killing by Israelis of German rocket scientists working for Nasserist Egypt and launches a missile attack on Israeli airbases just before the Six-Day War starts. Egypt is saved and Sinai is not occupied, but Israel continuesto exist. The Arab armies do not liberate the holy lands, despite their newly gained decisive advantage, proving the needlessness of the war and how Abdel Nasser’s pan-Arab rhetoric was just a stalking horse for his ambitions. Throughout the story, we are also exposed to the horrifying scenes of torture with Egyptian scientists thrown in prison at the behest of the Soviets. The criticisms here are clearly directed at home, and the hero is substantive, with his own internal demons and a love story with a foreign woman to boot.

The Accursed Experiment centers on a hapless hero who, just in the nick of time, gains superpowers to rescue Egypt from a set of impending scientific disasters, such as acid rainstorms, Israeli attacks, and infections. It is a distinctively Egyptian story, with lots of tongue-in-cheek criticisms of Egyptian disorderliness and ironic portrayals of the country’s leaders as responsible, open to criticism, and scientific in their response both to the acid storm and the Israeli attack. (The army cooperates with the Bedouins in Sinai to slow the Israelis down enough for a top-secret Egyptian satellite weapon to blast away the invading troops and tanks). Like Muhammad Al-Bidewi’s story, the onus is on the Egyptians, pointing out defects on the home front, but in a way that leaves hope for the future.

In other words, science fiction has become a refuge from the concerns of realist literature and the debilitating problems of everyday Arab life. Science fiction is the one way you can talk about Palestine quite directly, especially in a country like Egypt. It is the one place in which you can fight back even if you are not Prince Charming or a Rambo lookalike. And if it is pulp science fiction, it is popular. In Arabic literature, pulp is the only space you can fight the Israelis and win. Historically, this is a major development. As Syrian researcher Muhammad Al-Yassin has documented, Arabic science-fiction authors avoided Palestine for a very long time. Youssef Al-Sibai, who was appointed Minister of Culture by Sadat in the 1970s, only hinted at the question of Palestine in his science-fiction novel You Are not Alone, even though most of his war stories were about Palestine.40 To date, only Syrian science fiction has dealt with Israel and the United States, most notably Taleb Omran in The Dark Times.41

We have to be careful in how we define realism. Writing a novel is a kind of social science experiment, in which you study people and the contexts of their lives, and find something to say about their (real or imagined) behavior. In science fiction, you take this concern to a whole other level by building worlds, drawing the very rules of the game and going beyond the existing set of conditions of the here and now. That is why Marxist literary theorist Raymond Williams famously described science fiction as the supreme example of realism.42 In historically inspired science fiction, for instance, so as to realize we can influence our fate, we reminisce about the past and all the mistakes made. Could any branch of science fiction be more relevant to Palestine than this? You do not have to take my word for it—there is a new ChiZine Publications anthology, Other Covenants: Alternate Histories of the Jewish People, that is more convincing than I ever could be.

The same goes for parallel-dimensions science fiction. Reading about alien races and humans living side-by-side, or about ourselves living in an alternate and simultaneous reality, can again teach us that what we do matters. But there is nothing quite like good old-fashioned, hard science fiction, with space exploration and colonization, and inventions meant to solve problems in a feasible and convincing way so as to improve people’s lives. This definitely includes military science fiction, into which some Muslims and at least one Arab have already entered persuasively. For example, the Lebanese-Australian writer Jeremy Szal, Malaysian Azrul Jaini, Senegalese Mame Bougouma Diene, Indonesian Aditya NW, and Filipina Kristine Ong Muslim.43

World building, in many ways, is the equivalent of nation building in our more humdrum world. For a science-fiction example, let us use “Unification,” a two-part episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation. Spock is secretly on Romulus and stumbles onto something profound that convinces him to remain and continue on his peaceful mission. The Romulans, a related race, are reviving the old Vulcan alphabet, setting them on the same evolutionary course as Spock’s people. For a parallel on Earth, Afghani author AbdulWakil Salamlal points to one of the founders of the Pashtun people, the Sufi warrior mystic Bayazid Pir Rokhan. Not only did he fight against the authority of the Mogul emperors in India, but he also helped invent the Pashtun alphabet, incorporating Arabic script into his people’s language.

Was it not Barbara Harlow who argued that “imaginative writing was a way to gain control” (my italics) over history and culture—the record of actual events—which she considered to be just as important as armed struggle itself?44 Or as she put it more colorfully, “she rejected the ‘roses that spring from a dictionary or diwan,’ gathering to her heart the ‘roses’ that ‘grow over the wounds of the warrior.’”45 Surrealism and other modes of fantastical literature can engage in many of these world-building exercises too, but not nearly as constructively—in the literal sense of the word—as science fiction. That is what makes science fiction so empowering.

Just look at the mostly non-Arab authors listed in this piece. Aditya NW sets his novel BeastTaruna in a world in which Japan won the war and Indonesia is still struggling for its independence, with a youthful cast of superheroes saving the day. Azrul Jaini’s Galaksi Muhsinin (2008) constructs an entire universe in which Muslims have a galactic empire, reviving the Islamic Caliphate in the process. (Azrul Jaini also proves Nejm’s point about history and utopia, since Jaini once wrote a still-unpublished novel about an Egyptian MiG-21MF pilot in the October War.) Szal has multiple military fantasies, covering every theme imaginable. Colonization and the toll it takes on the colonist himself comes out in “Ark of Bones” and “Dead Men Walking.” Healing old wounds, facing up to one’s own brutality, and making peace with a supposed enemy all come out in “Inkskinned,” while fighting tyranny is central in “The Galaxy’s Cube” and “The Bronze Gods.” “These Six Walls” is clearly in the resistance genre, with aliens residing in something like the U.S.-occupied green zone and disguising themselves as humans to penetrate resistance cells. The same goes for “Walls of Nigeria,” which features an alien invasion in a third world setting.

Now, let us take another look at the two aforementioned Egyptian pulp science-fiction novels. The heroes in both are quasi antiheroes, a brand of protagonist almost unknown in Arabic literature until Ahmed Khalid Tawfik bequeathed us characters like Rifaat Ismail, Abeer, and Dr. Alaa Abd Al-Azim.46 The same is true for the hero of The Accursed Experiment, a commoner with bad health. This means, in turn, that Arabic realist literature is not nearly as so-called realistic as many presume.

Epilogue—A Spycam on the Future

If you look at the non-science fiction variety of pulps, you often find scenes of a man overpowering a small army of hoodlums with his bare fists. This is the case of the Impossible Man series by Nabil Farouk and the Professional Sniper (القناص محترف) series, both replete with outlandish confrontations with Israelis and people from the United States.

This is a far cry from anything penned by Tom Clancy or even Ian Fleming. The individual is at the center of the works by all these novelists—more so in the case of the British writers—and the range of heroes is vast, with desk-jockey analysts, assertive military men, philandering spies, and working-class Joes. The range of authors and literary styles is impressive as well—Frederick Forsythe, John le Carré, Kyle Mills, Robert Ludlum, Martin Cruz Smith, William Patterson, Sidney Sheldon, Graham Greene, John Gardner, Len Deighton, Charles D. Taylor, Clive Cussler, Morris West, Stephen Coonts, Craig Thomas, A. J. Quinnell, Dick Francis, Ruth Rendell, and Walter Wager, to name a few. And let us not forget Jack Higgins and Andy McNab, whose heroes often operate in the hazy world between espionage and the special forces.

While there are some prominent Egyptian spy novelists, such as Ibrahim Masoud, Salih Morsi, Nabil Farouk, and Ahmed Khalid Tawfik, it is not a coincidence, I think, that the spy novel is not a well-developed genre in Arabic literature. This is also a complaint frequently made in relation to the absence of numerous genres in Arabic literature.47 But by moving into resistance literature, we can hit multiple birds with one science-fiction stone.

Notes

- ↩ For the author’s meager contribution to resistance literature in the science-fiction genre, please see “Egyptian Science Fiction: Criticises Arabs”,Levant News, February 7, 2019.

- ↩ See the online reprint in Arabic, Mohammad Naguib, “سلاح من العفن,” Al-Mayadeen, January 25, 2018.

- ↩ Kawthar Ayed, “Science Fiction Literature in the Arab West,” Science Fiction 12 (2009): 19.

- ↩ Emad El-Din Aysha, “The Prescience of a 2001 Egyptian SF Novel: America 2030,” ArabLit: Arabic Literature and Translation, January 9, 2019.

- ↩“The Director of the Egyptian Society for Science Fiction on Arabic SF’s Past, Present, and Future,”ArabLit: Arabic Literature and Translation, March 28, 2018.

- ↩ Emad El-Din Aysha, “A Dialogue with My Friend the Resistance Author!,” Levant News, January 23, 2019.

- ↩ Al-Sayyid Nejm, “The Space of Resistance in the Novels of the Noble Prize Winner,” Al-Qahira, January 1, 2018,8–9.

- ↩ Shawki Badr Yousef, “Resistance and War in the Arabic Novel,” Azzaman International, May 31, 2012.

- ↩Resistance in Italian Culture: Literature, Film and Politics Conference, University of Sussex, 2018; Jeroen Dewulf, Spirit of Resistance: Dutch Clandestine Literature During the Nazi Occupation (Rochester: Camden House, 2010); Margaret Atack, Literature and the French Resistance: Cultural Politics and Narrative Forms, 1940–1950. (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1989).

- ↩ Yasmín Rojas, “Everything is Political, Including Poetry—Interview with Margaret Randall,” Literal: Latin American Voices, April 26, 2018; Lou Dear, “Epistemology and Kinship: Reading Resistance Literature on Westernised Education,” Open Library of Humanities 3, no. 1 (2017): 1–22; Audrey Goodman, “Engaged Resistance: American Indian Art, Literature, and Film from Alcatraz to the NMAIby Dean Rader (review),” Studies in American Indian Literatures 25, no. 1 (2013): 125–28; Mark P. Williams, “Literature of Resistance, as Literal Resistance: The Seven-Author Novel Seaton Point,” Werewolf, August 4, 2011.

- ↩ Toyin Falola, “In Memoriam: Barbara Harlow, 1948–2017,” Life & Letters, January 31, 2017.

- ↩ The one exception to the rule is Dr. Lubna Ismail at Cairo University, who taught George Orwell with Mahmoud Darwish and Radwa Ashour. But even she has been struggling. More recently, Nejm told me that even some Palestinian publications were no longer eager to publish his articles on Palestinian literature and culture!

- ↩ Nejm, “The Space of Resistance in the Novels of the Noble Prize Winner.”

- ↩ Shawqi Abd Al-Hamid Yihya, The Novel in October 1973. (Cairo: Dar Al-Hilal, 2017), 107.

- ↩ Yihya, The Novel in October 1973, 106–9.

- ↩ See also the first issue of the International Journal of Persian Literature (2016), which deals extensively with Iranian war literature. Amir Moosavi, “Dark Corners and the Limits of Ahmad Dehqan’s War Front Fiction,” Middle East Critique 26, no. 1 (2016): 1–15; Pedram Khosronejad, ed., Iranian Sacred Defence Cinema: Religion, Martyrdom and National Identity (Canon Pyon: Sean Kingston, 2012).

- ↩ His nickname was Che and a film of the same name came out in 2014, celebrating his exploits.

- ↩ Chamran was originally a scientist living in the United States. To add to the irony, he received his own resistance training in Cuba, Algeria, and Egypt. For more information on the Art Club, see “A Brief Review of the History of ‘Hozeh Honari’ and Its Performance,” Hozeh Honari—Islamic Development Organization, http://hozehonari.com.

- ↩ Shawqi Daif, Heroism in Arabic Poetry (Cairo: Dar al-Mararif, Iqraa Series 331, 1970), 12–13.

- ↩ Daif, Heorism in Arabic Poetry, 12.

- ↩ May Yousef Khalif, Heroism in Jahili Poetry, and Its Effect on Storytelling Modes (Cairo: Dar Qbaa, 1998), 79, 83–84.

- ↩ Al-Sayyid Nejm quoted in Aysha, “A Dialogue with My Friend the Resistance Author!”

- ↩ Khalif, Heroism in Jahili Poetry, 87–88, 90–91.

- ↩ Abbas Khidr, Resistance Literature (Cairo: Dar Al-Kitab Al-Arabi, Cultural Library Open University Series 203, 1968), 4–6, 20–22, 25–27, 87–91.

- ↩ Al-Sayyid Nejm, “The Genius of the October Victory Was Never Written Down,” Dar Nashiri for Electronic Publishing, October 4, 2004.

- ↩ This is all the more impressive given Syria’s own rich contribution to the genre, with Hanna Mina, Ali Aqla Ersan, Hassan Hamid, Nizar Qabani, Muhammad Al-Maghout, and Saad Allah Wanus. A great many of these Syrian authors are also of Palestinian origin.

- ↩ For a psychoanalytic study of the significance of these two contrasting stories, see Emad El-Din Aysha, “Islamist Suicide Terrorism and Erich Fromm’s Social Psychology of Modern Times,” Journal of Social and Political Psychology 5, no. 1 (2017): 89–90.

- ↩ This is something that has been said about Habib Ahmadzadeh’s work because of his deep character portrayals and condemnations of war, punctured nonetheless by victories and military acumen.

- ↩ Ibrahim Fathi, introduction to The Locusts Love Watermelons, by Radi Shehata (Cairo: Masriyah, 1990), 6.

- ↩ Fathi, introduction, 8.

- ↩ Fathi, introduction, 9.

- ↩ Emad El-Din Aysha, “Islam Sci-Fi Interview of Algerian Fantasy Author Djamel Jiji,” Islam and Science Fiction, January 17, 2018.

- ↩ Ghassan Kanafani, Palestinian Resistance Literature Under Occupation, 1948–1968 (Cairo: Dar Al-Taqwa, 2016) 28, 46–48.

- ↩ Mauritania is an exemplary case of a country whose literary traditions rely both on folk songs and stories, as well as religious centers of teaching to protect the country’s Arab identity against French linguistic colonialism (“The Folk Dimension of Resistance Literature in the Era of the French Occupation of the Lands of Mauritania,” Mauritania Online, June 26, 2018; Ahmed Salem Bin Al-Mustafa, “The Role of Al-Mahdoura in Resisting Colonialism,” Mednasser blog, June 11, 2011.) The science-fiction author Moussa Ould Ebnou is a case in point, since he both utilized his knowledge of French to popularize African science fiction, while protesting the dominance of French in his native country during his early political career (Pierre Gévart, “Interview with Moussa Ould Ebnou,” Galaxies 46 [2017].)

- ↩ Nasser Al-Syyid Al-Nour, “The African Novel… The Roots of Linguistic and Cultural Resistance,” Al-Afreeqia 24, August 16, 2017. Resistance literature and postcolonial literature (ما بعد الكولونيالية) is particularly well-developed in sub-Saharan Africa, in part because it operates on multiplelevels, something many have keenly noted. It functions as anticolonial, antiracist, third world literature meant to redeem black people’s sense of self and shelter local languages and identities from the white colonial presence, as well as to position these ethnic-tribal divisions within the larger nation following independence. Al-Saghier Shamikh, “African Resistance and Independence Literature… Countering the ‘White Man’s Burden,’” Meem Magazine, November 25, 2017; Mustafa Attia Jouma Gouda, “The Problem of Language Post-Colonial Literature on the African Continent,” African Readings, April 27, 2017.

- ↩ For the overlap of past and future, and other identity-related issues in Palestinian literature, see Tahrir Hamdi, “Bearing Witness in Palestinian Resistance Literature,” Race & Class 52, no. 3 (2011): 21–42; Annelys de Vet, ed., Subjective Atlas of Palestine (Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 2007); Tom Hill, “Historicity and the Nakba Commemorations of 1998” (EUI Working Paper RSCAS no. 2005/33, European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, Mediterranean Programme Series, 2005).

- ↩ Nora Parr, “Five Things You Need to Know About 11th IPAF Winner ‘Dog War II’,”ArabLit: Arabic Literature and Translation, April 27, 2018.

- ↩ Irette Y. Patterson, “On Resistance: The Chosen One,”Strange Horizons, January 28, 2019.

- ↩ Khaled Gouda Ahmed, “Narrating the Imaginary and Moving Toward the Virtuous City,” Middle East Online, January 1, 2019.

- ↩ He fought there in 1948 and was part of the Free Officers Movement.

- ↩ Muhammad Al-Yassin, “Egyptian and Syrian Science Fiction: Novels and Novelists,” Science Fiction 10–11 (2009): 43–44.

- ↩ Raymond Williams, “Realism and the Contemporary Novel,” Universities & Left Review 4 (1958): 23–24.

- ↩ Mame Diene has written some very explicitly anticolonial stories, such as “The Broken Nose” and “Black and Gold” (fantasy stories of postcolonial resistance), “Sgotemmeli’s Song” in Afrosfv3 (a space opera with galactic battles), and “Another Day in the Desert” (a story about Tuareg resistance set in the same universe as “Sgotemmeli’s Song,” just a few hundred years prior).

- ↩ William Grimes, “Barbara Harlow, Scholar on Perils of Resistance Writing, Dies at 68,” New York Times, February 9, 2017.

- ↩ Barbara Harlow quoted in Liz Fekete, “Barbara Harlow 1948–2017,”Race & Class Blog, January 30, 2017.

- ↩ Emad El-Din Aysha, “In Memoriam: Ahmed Khalid Tawfik, the Man and the Mission,” ArabLit: Arabic Literature and Translation, November 21, 2018.

- ↩ Hassan Blasim, forward to Iraq + 100: Stories from a Century After the Invasion (Manchester: Comma, 2016), viii.