Art reflects the world around us, but does art not also help shape the society we live in? John Molyneux—a Marxist writer with a prodigious output over many decades, who has also had a lifelong interest in visual art—tackles this fascinating subject, in this extended piece based on a forthcoming book.

This is a very compressed version of a much longer argument that will appear in a forthcoming book on The Dialectics of Art. Both the book and this article are written in the belief that visual art matters, not only to the minority who are passionate about art, but objectively to society as a whole and its development.

It is not that paintings or sculptures will be the prime movers in the immense social changes that will be necessary if humanity it is to have a decent future. That role has been and will be played by mass popular struggle. Art matters because of its ability to articulate in visual imagery the social consciousness of an age, in a way that aids the development of the human personality, and our collective awareness of our natural and social environment.

The Dialectics of Art

Visual art is part of the superstructure of society. Its development is conditioned by the development of society’s economic base—the level of economic development and the social relations of the era. For a Marxist and historical materialist this is ABC. As Engels noted in his speech at Marx’s graveside:

Just as Darwin discovered the law of development or organic nature, so Marx discovered the law of development of human history: the simple fact, hitherto concealed by an overgrowth of ideology, that mankind must first of all eat, drink, have shelter and clothing, before it can pursue politics, science, art, religion, etc.; that therefore the production of the immediate material means, and consequently the degree of economic development attained by a given people or during a given epoch, form the foundation upon which the state institutions, the legal conceptions, art, and even the ideas on religion, of the people concerned have been evolved.

Thus the cave paintings of Chauvet or Lascaux reflect the social relations of a classless hunter- gatherer society. The art of Medieval Europe reflects a relatively static feudal society in which the church was a major landowner and Christianity was the overarching hegemonic ideology. The art of the Renaissance (Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael etc) and the early modern period (Holbien, Caravaggio, Rembrandt, Vermeer etc) reflects a society in which that feudal order is threatened by a rising bourgeoisie.

Modernist art, from the mid-nineteenth century onwards, with its rapid succession, different art movements and styles—realism, impressionism, symbolism, expressionism, fauvism, cubism, Dadaism, surrealism and so on—reflects the maelstrom of economic and social change unleashed by the industrial revolution and modern capitalism: ‘All that is solid melts into air’, as Karl Marx and Marshall Berman both put it.

But when we look more closely at the history of art we see that art does not simply or passively reflect the economic base like a mirror. Rather art is conditioned by the society from which it emerges in a multitude of ways—by the demands of those (Popes, aristocrats, governments, corporations etc) with the power to commission it; by the materials available; and by the dominant ideology of the era, by the way the social relations and major events of the time enter and shape the artists imagination. But the artist also actively responds to society, sometimes in approval and celebration, sometimes in anger or despair, sometimes with a desire to escape reality. Someone who is punched on the jaw may fall down, run away or hit back. In each case their behaviour ‘reflects’ being punched but how they responded looks very different. Again Engels expresses this very clearly.

According to the materialistic conception of history, the production and reproduction of real life constitutes in the last instance the determining factor of history. Neither Marx nor I ever maintained more…The economic situation is the basis but the various factors of the superstructure—the political forms of the class struggles and its results…and even the reflexes of all these real struggles in the brain of the participants, political, jural, philosophical theories, religious conceptions and their further development into systematic dogmas—all these exercise an influence upon the course of historical struggles, and in many cases determine for the most part their form. The whole great process develops itself in the form of reciprocal action.

In short there is a dialectical relationship between art and society. Thus two major artists from the same period and the same part of the world may respond to the same historical events in very different ways. One example would be Rubens and Rembrandt. Rubens (1577 – 1640) was based in Antwerp and Rembrandt (1606-1666) in Amsterdam. Rembrandt’s art was very much a product of the Dutch Revolt, a bourgeois revolution which established the Dutch Republic, while Rubens’ art was commissioned by and expressed the aristocratic counter-revolution of the Habsburg Empire.

Another example is the contrast between John Constable (1776 – 1838) and JMW Turner (1775- 1851), two contemporaries working in England during the Industrial Revolution. While Constable paints magnificent rural idylls that evoke a stable English countryside where everyone knows their place, Turner gives expression, equally magnificently, to the dynamic forces that are changing the world.

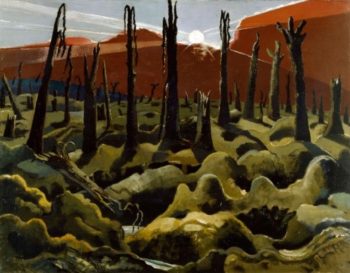

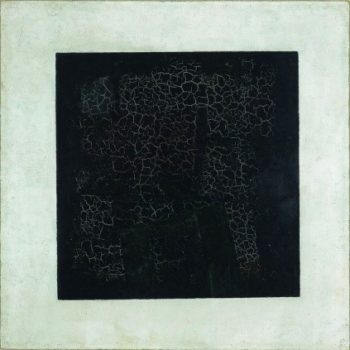

Another period that gave birth to contrasting tendencies was the First World War. Clearly the scale and horror of this event influenced the great artists of the day. Importantly, however, this was often conveyed in starkly contrasting artistic styles. Thus the war produced both art that depicted the horror of the trenches like that of Paul Nash and Otto Dix, but also the abstract and conceptual art of Malevich’s Black Square (1915) and Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917), that tried to challenge the entirety of ‘bourgeois’ culture.

The Dialectic of Differentiation

As well as this dialectic between art and society there is also an internal dialectic within modernist art, which of course is deeply shaped by processes in the wider society.

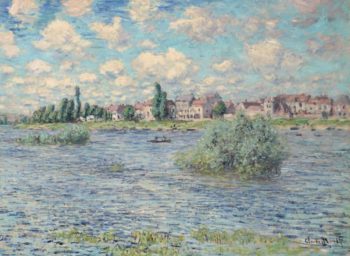

One aspect of this is what I would call a dialectic of differentiation. Each succeeding art movement, and there can be several within a single generation, seeks to differentiate itself from the art that went immediately before. In the process there is both gain and loss. Thus Impressionism in France in the 1870s sought to differentiate itself from both the academic art that was dominant in the official Salon and from the realism of Courbet by emphasising effects of light en pleine air (out of doors). The result was brilliant innovation by artists such as Monet, Pissarro, Sisley and Renoir, that changed European art forever. But this involved a certain loss of focus on form and the great artists that came immediately afterwards such Seurat, Van Gogh and Cezanne all built on the achievements of Impressionism with light but also tried in different ways to reintroduce form. In other words there was a dialectical development.

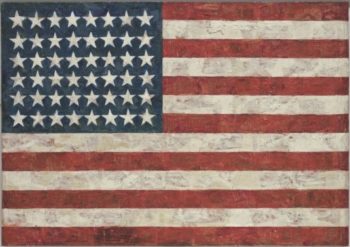

We see a similar process in America in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s with Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art and Minimalism. Abstract expressionism reached its peak in the late forties with the drip and flick paintings of Jackson Pollock and the colour field paintings of Mark Rothko. It rejected altogether the depiction of three dimensional objects and counterposed itself to the ‘kitsch’ popular culture of the masses. No sooner had abstract expressionism established itself than it was challenged, first by transitional figures such as Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, and then, even more dramatically, by Andy Warhol whose art was based precisely on the depiction of the three dimensional objects and persons of popular culture such as Campbell Soup cans, Brillo Pads, Marylin Monroe and Elvis. This in turn produced the reaction of minimalism with the likes of Carl André, Dan Flavin and Donald Judd who used everyday materials such as bricks, neon tubes and steel boxes, to produce abstract sculptures shorn of pop culture references.

The Dialectic of Democratisation

In tandem with this dialectic of differentiation there has been a dialectic of democratisation (versus elitism). This is clearly in response to the emergence of modern democracy following the French Revolution and the rise of the working class and it has expressed itself in the subject matter of art, its style and its materials.

In terms of subject matter one land mark was Courbet’s The Stone Breakers of 1849 following the 1848 Revolution. This depicted two ordinary labourers at work on a scale and in a manner that would previously have been reserved for kings, queens and figures from Greek mythology. Another democratic move was Manet’s nude Olympia in 1865. In one way Olympia stood in a tradition of representing the female nude that stretched back to Botticelli, Titian and Velazquez but it was significantly different. Manet’s painting depicted not an aristocratic courtesan masquerading as Venus but a Parisian working girl from the faubourgs. Moreover she does not pout seductively but coldly returns the viewer’s gaze. These differences scandalised the Parisian bourgeoisie and its art critics.

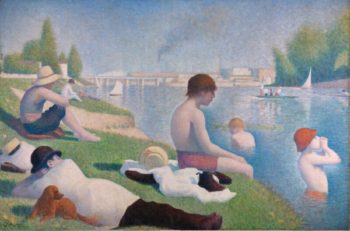

Seurat’s Bathers(1883) went further, painting ordinary workers sitting on the banks of the Seine with factories in the distance in the manner of a huge composition by Piero Della Francesca. Van Gogh painted subjects that would never before have been considered worthy of artistic representation such as his chair and his boots. Cezanne painted apples with the same gravity and seriousness that Raphael brought to his depictions of the Madonna.

There was also a profound change in portraiture. All the main artists from Holbien to David and even the democratically inclined Goya painted the royalty and the rich. Van Gogh and Cezanne painted only everyday people like the local postman or card players. Toulouse Lautrec painted the prostitutes of Montmartre without glamourising them. The early Picasso, in his blue and rose periods, showed the very poorest and most marginalised.

Often the democratisation of subject matter takes the form of trying to make art of a topic that would hitherto have been seen as inherently unartistic. Jasper John’s Flag paintings and Tracey

Emin’s My Bed are examples of this.

When it comes to materials there is a massive opening up of usage. Up to the mid 19th century oil painting reigns supreme along with marble and bronze in sculpture. It is Picasso and Braque who break new ground with their synthetic cubist works of 1910-11 which incorporate scraps of newsprint, bits of table cloth and other every day materials. Similarly Picasso starts to use everyday objects in his sculpture as in his Bulls Headmade of a bicycle seat and handlebars. After that the flood gates open. Duchamp presents his ready-mades (urinals, bottle racks and bicycle wheels); Pollock uses industrial paints; Rauschenberg uses street detritus picked up round the Bowery and East Village. Carl André uses industrial bricks and blocks of wood; Damien Hirst uses stuffed animals in formaldehyde; Jeff Koons displays baseballs and vacuum cleaners; and Emin shows actual used condoms, stained knickers and empty bottles.

Capitalism and Art

But all the while this push to democratisation is taking place there is an equal pull in an elitist direction through the power of big capital and the grip it has on the art world. The bourgeoisie exercises hegemony across the cultural field but of the three basic art forms—literature, music and visual art—the dominance of big money is greatest in visual art. Visual art has tended to be embodied in singular physical objects that can be purchased by private collectors and state institutions in a way that is not the same for poems, novels, songs or scores. A successful writer sells a million copies of their book at €10 a copy. A successful painter sells one painting for a million or even ten million euros to one collector or museum. The physical nature of art also means that costs of production and storage play a role in reinforcing the power of the financial and institutional elite. A Henry Moore sculpture or Picasso’s Guernica costs a lot to make and cannot be stored in the attic.

In the 19th century the art world remained under the control of the aristocratic ancien régime but in the 20th century modern art was largely taken over by corporate capital, especially American capital. A key role was played by the Rockefeller Family who established, under the directorship of Alfred H Barr, the single most important modern art institution in the world, MOMA (Museum of Modern Art) in New York. But think also of the other key US museums—the Guggenheim, the Whitney—and the key contemporary collector, the billionaire Larry Gargosian and his British equivalent, Charles Saatchi.

Consequently the history of modern art is a history of rebellion from below followed by incorporation into the establishment. The impressionists began as derided outsiders and now Monet is as much chocolate box as Constable. Van Gogh could not sell his work and lived in poverty. In 1990 his Portrait of Dr. Gachet sold for $82.5 million to a Japanese manufacturer. Picasso made it from impoverished bohemian in Montmartre to multi-millionaire and, probably, billionaire in his own lifetime. The abstract expressionists began as wild, defiant outcasts but Peggy Guggenheim put Jackson Pollock on her pay roll and by the late fifties they were being covertly promoted by CIA, as exemplars of American ‘freedom’ in the Cold War. Damien Hirst was seen as a kind of cockney enfant terrible in the 1990s but now epitomises the artist as entrepreneur with an estimated fortune of $300 million. Tracey Emin, with her plebeian roots, and the radical graffiti artist, Banksy, have followed similar trajectories. Writing in 1936 Trotsky summed up the process as follows.

Every new tendency in art has begun with rebellion. Bourgeois society showed its strength throughout long periods of history in the fact that, combining repression, and encouragement, boycott and flattery, it was able to control and assimilate every “rebel” movement in art and raise it to the level of official “recognition.” But each time this “recognition” betokened, when all is said and done, the approach of trouble. It was then that from the left wing of the academic school or below it—i.e. from the ranks of new generation of bohemian artists—a fresher revolt would surge up to attain in its turn, after a decent interval, the steps of the academy. Through these stages passed classicism, romanticism, realism, naturalism, symbolism, impressionism, cubism, futurism.

Every new tendency in art has begun with rebellion. Bourgeois society showed its strength throughout long periods of history in the fact that, combining repression, and encouragement, boycott and flattery, it was able to control and assimilate every “rebel” movement in art and raise it to the level of official “recognition.” But each time this “recognition” betokened, when all is said and done, the approach of trouble. It was then that from the left wing of the academic school or below it—i.e. from the ranks of new generation of bohemian artists—a fresher revolt would surge up to attain in its turn, after a decent interval, the steps of the academy. Through these stages passed classicism, romanticism, realism, naturalism, symbolism, impressionism, cubism, futurism.

Sometimes the quality of the actual art is greatly damaged by this incorporation (Dali and Hirst are examples) and sometimes it survives. (Miro and Bacon)

The art of today continues to exhibit these contradictions and pressures and continues to develop dialectically. Since the turn of the millennium two trends have dominated the Western art world. The first is art of increasing size based on ever increasing production values. In this category I would include the likes of Damien Hirst, Jeff Koons, Anthony Gormley, Ai WeiWei and Anish Kapoor. While some of this art, such as Gormley’s Angel of the North, can be visually powerful much of it is quite vacuous, its main feature being simply its scale and expensiveness. Anish Kapoor is a case in point. In 2003 he installed Marsyas, designed with engineer Cecil Balmond, in the Tate Modern Turbine Hall; a 150 meter long, ten story high sculpture, which may well be one of the largest works ever shown in a gallery. Then came the ArcelorMittal Orbit or Orbit Tower, also designed with Cecil Balmond, for the London Olympics—the Tower, commissioned following a decision by London Mayor, Boris Johnson, and Olympics Minister Tessa Jowell, was 114.5 meters high and cost approximately £19 million, largely provided by Anglo-Indian steel billionaire, Lakshmi Mittal.

The Social Turn

At the opposite end of the spectrum, emerging from left field, has been what is often called ‘the social turn’.The end of the nineties saw the development of ‘Relational Art’. In relational art the work involves, and is‘completed’ by the participation of members of the viewing public. The artwork is the social relations it gives rise to. The weakness of much early relational art was its blandness: the social relations it invoked tended not to go beyond the harmonious and convivial—as in Carsten Holler’s Test Site in which he installed several huge metal slides in the Tate Modern Turbine Hall for visitors to ride down. Then, under the influence of the anti-capitalist movement and re-emergence of a left in the US, relational art radicalised and politicised into ‘Socially Engaged Art’. It strove to move out of the galleries to work with people in working class and oppressed communities. An example from Britain is Jeremy Deller’s restaging of the Battle of Orgreave from the great Miners Strike of 1984-5 and socially engaged artists played a significant role in Occupy Wall Street in 2011.

The social turn has produced much more interesting and challenging art than the corporate art of the Kapoors and the Hirsts, but it also has its problems. Just as impressionism explored light at the expense of form, so socially engaged art’s focus on democratic process has tended to sacrifice the making of an aesthetically powerful object. But that may be remedied in a new dialectical synthesis and my guess is that the challenge of the total environmental crisis of the Anthropocene may lead to this direction.

In any event the dialectics of art will continue.